Positive Approaches Journal, Volume 8, Issue 3

| Site: | My ODP |

| Course: | My ODP |

| Book: | Positive Approaches Journal, Volume 8, Issue 3 |

| Printed by: | |

| Date: | Friday, February 27, 2026, 2:15 AM |

Positive Approaches Journal | 5

Volume 8 ► Issue 3 ► 2019

Rights, Risks, and Restrictions

Introduction

Taking risks, making bad decisions, and experiencing the consequences of one’s choices are often unacknowledged yet essential parts of living an everyday life – a life that is no different than one lived by a person without a disability. At the same time, most of us are in positions where we have some degree of professional responsibility to ensure that individuals with disabilities are protected from harm.

Balancing the obligation to protect individuals’ health and safety with the obligation to protect individuals’ rights is extremely difficult. Indeed, these obligations are frequently seen as mutually exclusive; how, for example, does one manage a situation where an individual with diabetes insists on eating sweets and drinking soda? What is one to do when an individual chooses to be in a relationship with a person who is verbally abusive? Simply put: when does choice override risk, and vice versa?

In this issue, we begin to explore the question of “choice versus risk” by presenting the perspectives and experiences of professional clinicians in the areas of risk, rights, and restrictions. It is our hope that these articles will help readers understand how to make safety and rights complement one another through person-centered practices.

—Ronald Melusky, Director of Program Operations, Office of Developmental Programs

Positive Approaches Journal | 6

Data Discoveries

The goal of Data Discoveries is to present useful data using new methods and platforms that can be customized.

In delivering services to individuals, there are often complicated and unpredictable issues around the rights people have to choices, the risks they are entitled to and permitted to take, and the restrictions that may be required for safety. Each of these

elements are specific to each individual, both the person receiving services and the person supporting the individual or participant.

In this issue, Data Discoveries seeks to get feedback from across the community on how individuals perceive and experience rights, risks, and restrictions. By using a ‘word cloud,’ responses to a survey distributed across Pennsylvania are presented. Both the size of the word and the color of the word provides information on how often it was mentioned. The size of each word indicates how often it was reported to describe rights, risks, or restrictions, with words that are mentioned more often being larger. Color is also used to indicate if a word was reported more often for rights, risks, or restrictions, with a darker color indicating that a word was mentioned more often than lighter colored words. Separate word clouds were generated for rights, risks, and restrictions because although these concepts often overlap, contrasting their differences is helpful to capturing how they interact. To view the different word clouds, click one of the boxes along the top of the Dashboard labeled ‘Rights’, ‘Risks’, and ‘Restrictions’ and the corresponding word cloud will appear. Results from the survey are linked automatically to Tableau, which was used to create the word cloud, and will be updated weekly for a limited period of time.

To take the survey about rights, risks and restrictions that provides data for the word clouds, click on the box labeled ‘Take the Survey Here!’ or visit: https://drexel.qualtrics.com/jfe/form/SV_0HbHExo9HyjRgNL

Learn more about rights, risks, and restrictions by first logging into your MyODP account and then visiting the following links for trainings: Understanding Safety and Your Responsibilities, Foundations of Recognizing and Mitigating Risk, & Addressing Day to Day Risks with the Team.

Bell | 7-14

Volume 8 ► Issue 3 ► 2019

Analyzing Positive Behavioral Support through One Individual’s Experiences

George Bell IV

Abstract

Positive Behavior Support (PBS) in conjunction with effective programming provides an effective paradigm for supporting individuals with complex needs. The framework of PBS contains an assortment of approaches that can be implemented successfully

in a community setting, while still emphasizing the concepts of individuality and Everyday Lives. This article will analyze one person’s experiences and demonstrate the effectiveness of implementing a program based on interventions grounded in the

philosophy of PBS.

Introduction

Within the context of community-based services, the system is sometimes faced with challenges that seem unsurmountable. Yet, experiences demonstrate that with the application of strategies grounded in the philosophy of Positive Behavior Support

(PBS), in conjunction with effective programming, even the most complex situations can be effectively managed. 1

Case Study

Consider this case in which a 14-year-old male presented with pervasive medical and behavioral needs. As he aged, the family described increasing difficulty to manage his needs. He was receiving supports through multiple systems, yet locating resources that possessed not only medical expertise, but could also support developmental and behavioral challenges, was difficult.

The response became all too familiar. Providers were unable to provide support based on the concurrence of behavioral and medical issues. With each passing day, the challenge of supporting this individual increased, eventually resulting in recommendation for Residential Treatment Facility (RTF) placement. Referrals were made, but the team encountered similar responses. Programs were unable to support the co-occurrence of medical and behavioral needs. Eventually, the family became unwilling to accept discharge from an emergency room, resulting in an acute psychiatric placement.

Upon admission to the acute psychiatric setting, the first task facing the hospital’s team was to mitigate the significant health and safety risks resulting from self-removal of the tracheostomy and G-tube. Initially, the only feasible mechanism of prevention included frequent 4-point restraint use. Eventually, though, the team developed a modified arm brace that helped prevent removal of the medical devices. This was a significant turning point in achieving stabilization. Further development of interventions continued with utilization of psychotropic medications and behavioral-based techniques. Still, the successful reduction in removing medical devices was the most significant achievement and paved a path to potential community-based placement.

Eventually, a provider agency committed to developing a program for this child. During transition, the agency initiated a comprehensive Functional Behavioral Analysis (FBA), employing a host of assessment and screening activities to better understand the function and motivating factors of his behaviors. Thorough assessment is a cornerstone of PBS. 2 One process employed during transition was the Biographical Timeline (BT). The BT is a critical element used to generate data on a person’s history through facilitated team discussions. The BT facilitator documents the information generated on a visual timeline. This process enables the team to learn from the person’s history, focus in on their role as supporters, and develop empathy and understanding for the person’s experiences. 3 This process provided a comprehensive understanding of previous medical and behavioral challenges.

Environmental design is an integral part of program development and an important aspect of PBS. 4 It is a proactive process to create a setting specifically geared towards a person’s needs. It is effective because it seeks to modify potentially hazardous or anxiety-provoking stimuli, while also incorporating characteristics to foster success. The foundation of the program developed for this individual included the provision of a 1-person home with 2:1 staffing support and 24-hour nursing care. Other adaptations included specialized padding on dangerous surfaces, Lexan to replace glass, a fenced-in yard, limited access to dangerous items, and incorporation of specialized furniture.

Another important evaluation included completion of a sensory assessment. According to Reynolds et al., evaluating the impact of sensory integration can support professionals to understand “… how sensory experiences serve as antecedents for undesirable behaviors and identify positive sensory experiences to use as rewards for reinforcing desirable behaviors.” 5 By fully exploring the impact of sensory integration, it provided framework for additional modifications, including development of a sensory room. It also led to the installation of a swing, which can have calming affects in over-stimulated children. 6 Not only was this a helpful coping mechanism, but it was found to be useful in pairing with other less preferred activities. It became a means to facilitate the completion of adaptive and self-care skills that were otherwise difficult to perform.

The team believed that communication deficits were a primary source of issues aligned with self-regulation. The implementation of a functional communication assessment and training is another intervention grounded in the philosophy of PBS. 7 The team implemented the Verbal Behavioral Milestones Assessment and Placement Program (VB-MAPP). The purpose of this assessment is to evaluate baseline skills and design intervention strategies. 8 Using the VB-MAPP, the team developed strategies that enhanced the opportunity for communication. Specific strategies that were developed included the use of adapted sign language and implementation of a modified version of the PECS (Picture Exchange Communication System).

Another critical component of success included implementation of a trauma informed environment with emphasis on consistency and predictability. 9,10 The agency sought to achieve this by fostering trust with supporters, describing this as a critical factor in achieving success. Efforts to provide consistency with staffing supports led to the development of trusting relationships, which in turn enhanced predictability in the child’s life. The team believed this was a significant antecedent to reducing concerning behaviors and improving success.

Although much focus was maintained on development and learning, there was also a need to incorporate comprehensive safety planning in response to crisis. Strategies highlighted resources to be utilized during the occurrence of challenging behaviors, such as the nursing supports to respond to the removal of medical devices. In creating a plan to mitigate this predictable behavior, chronic emergency room visits were often avoided. An on-site medical professional was able to provide treatment, avoiding the potential crisis that could accompany treatment from professionals unfamiliar with the individual. Eliminating these pitfalls was a significant driver in achieving success and furthered the team’s efforts towards the development of a stable environment.

In addition to the accomplishments of program development, it is still necessary to be flexible and willing to adapt to change. “PBS is an approach to behavior support that includes an ongoing process of research-based assessment, intervention, and data-based decision-making ….” 11 The team placed a great deal of emphasis on data collection and analysis as a means to capture progress, identify change, and recognize new challenges. The Antecedents, Behaviors, and Consequences (ABC) tracking tool was the primary mechanism used to collect data. This documentation is completed in hourly intervals and used to formulate interpretations related to target behaviors. The data is gathered and closely scrutinized each month. This ensures that significant change is quickly identified, which enables the team to update the health and safety plan within 24 hours. A change in this plan also sparks a process for informing and training staff. Therefore, when significant change is identified, the team can respond in a timely manner. It is through this continued emphasis on data collection that the team can respond effectively to changing needs.

Despite an assortment of barriers, this individual has not only remained in the community, but he has thrived. This is not to suggest that challenges no longer exist, as there are still intensive needs. Instead, the takeaway is that comprehensive assessment grounded in the philosophy of PBS can be a cornerstone in the development of effective individualized supports. Assessment helped to recognize specific needs leading to the creation of an environment that fostered success. In understanding the holistic person and creating an individualized program based on this knowledge, it has enabled this child to achieve what we hope for everyone: an opportunity to live an Everyday Life.

References

- Chartier, K., (2015). Outcome evaluation of a specialized treatment home for adults with dual diagnosis and challenging behavior. Journal of Developmental Disabilities, 21(2).

- Burke, M. D., Rispoli, M., Clemens, N. H., Lee, Y. H., Sanchez, L., & Hatton, H., (2016). Integrating universal behavioral screening within program-wide positive behavioral interventions and supports. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 18(1), 5-16.

- Barol, B., (2001). Learning from a person’s biography: An introduction to the biographical timeline process. Positive Approaches, 3(4).

- Carr, E. G., Dunlap, G., Horner, R. H., Koegel, R. L., Turnbull, A. P., Sailor, W., & Fox, L. (2002). Positive behavior support: Evolution of an applied science. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 4, 4–16.

- Reynolds, S., Glennon, T. J., Ausderau, K., Bendixen, R. M., Kuhaneck, H. M., Pfeiffer, B., Watling, R., Wilkinson, K., & Bodison, S. C., (2017). Using a multifaceted approach to working with children who have differences in sensory processing and integration. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 71(2), 1-10.

- Davis, T., Abdo, A. L., Toole, K., Columna, L., Russo, N., & Norris, M. L., (2017). Sensory motor activities training for families of children with autism spectrum disorders. Palaestra, 31(3), 35-40.

- Kincaid, D., & Horner, R., (2017). Changing systems to scale up an evidence-based educational intervention. Evidence-Based Communication Assessment and Intervention, 11(3-4), 99-113.

- Barnes, C. S., Mellor, J. R., & Rehfeldt, R. A., (2014). Implementing the verbal behavior milestones assessment and placement program (VB-MAPP): Teaching assessment techniques. Association for Behavior Analysis International, 30, 36-47.

- Gentry, J. E., Baranowsky, A. B., Rhoton, R., (2017). Trauma competency: An active ingredients approach to treating post-traumatic stress disorder. Journal of Counseling and Development, 95, 279-287.

- Hodgdon, H. B., Kinniburgh, K., Gabowitz, D., Blaustein, M. E., & Spinazzola, J., (2013). Development and implementation of trauma-informed programming in youth residential treatment centers using the ARC framework. Journal of Family Violence, 28, 679-672.

- Kincaid, D., Dunlap, G., Kern, L., Lane, K. L., Bambara, L., M., Brown, F., Fox, L., & Knoster, T., P., (2016). Positive behavior support: A proposal for updating and refining the definition. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 18(2), 69-73.

Biography

George Bell IV is the Regional Clinical Director for the Northeast Region’s Office of Developmental Programs, Bureau of Community Services. He has worked with the state office for nearly five years. Prior to his current position, he worked with a private provider agency for more than 20 years supporting individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities in community-based programs.

Contact

George Bell IV

PA Department of Human Services

Office of Developmental Programs

Northeast Regional Office

100 Lackawanna Ave

Scranton, PA 18503

(570) 963-4982

Gina Calhoun, Matthew Federici, and Sue Walther | 15-27

Volume 8 ► Issue 3 ► 2019

Wellness Recovery Action Planning and Mental Health Advanced Directives

Gina Calhoun, Matthew Federici, and Sue Walther

Abstract

When we think about recovery, we think about freedom from...freedom from addiction, freedom from anxiety controlling one’s life, freedom from stigma and discrimination, freedom from institutionalization.

Recovery is also freedom to – freedom to take risks to be the well person we want to be; freedom to explore a self-determined life based on hopes, dreams and goals; freedom to be included in one’s community.

The Wellness Recovery Action Plan (WRAP®) through a Peer Group Model offers the opportunity for participants to discover a self-determined well life and take action toward the freedom we want to achieve.

For the context of this article, we will focus on fidelity to the peer group model. For ease in reading the article and for readers new to WRAP®, please note the language of Wellness Tools. Wellness Tools are defined as “a list of things you

have done in the past, or could do to help yourself stay as well as possible, and the things you could do to help yourself feel better when you are not doing well.” 1, 2, 3 The Wellness Toolbox is the cornerstone of developing a WRAP®.

WRAP® is a designed plan to put your wellness tools into action. Developing a Wellness Recovery Action Plan® promotes self-determination; you can take action and make intentional decisions about your wellness.

In Pennsylvania, we recognize the right of people to have voice and choice in their lives, even in the midst of crisis. Pennsylvania Mental Health Advanced Directives are highlighted in this article.

The article is written in first-person language in an effort to recognize the value of “I” statements when sharing perspectives and to bring the evidence-based practice of a peer group model to life.

Introduction

I'm Gina Calhoun, a program director and trainer at the Copeland Center for Wellness and Recovery. At the Copeland Center, the practice of the Wellness Recovery Action Plan (WRAP®) is a shared peer group experience that leads to each person developing their own wellness plan to live a self-determined life.

I learned about WRAP®, after escaping from Harrisburg State Hospital to live on the streets. At that time, I didn’t have much hope for a meaningful life in the future. The WRAP® material helped me to shift my thoughts away from what’s wrong and towards what’s strong in my life. The WRAP® peer group experience offered the validation and support I needed to put these new thoughts into action. I love being part of the WRAP® community, especially when we work together to translate our values and ethics into practical applications. When we create strength-based approach with mutual learning and rich connections, endless possibilities emerge.

In 2010, WRAP® groups were recognized by the United States Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) as an evidence-based practice and listed in the National Registry of Evidence-Based Programs and Practices. 4 Researcher Dr Judith Cook from the Department of Psychiatry at the University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC) released the results of a randomized control trial study that demonstrated significant positive behavioral health outcomes for individuals with severe and persistent mental health challenges who participated in peer-led WRAP® groups. 5

Research studies on WRAP® from UIC revealed positive outcomes were tied to the fidelity of the WRAP® co-facilitation model. This model was based on specific values-based practices highlighted further in this article. As WRAP® expands to schools, the healthcare system and developmental programs, we are called to ensure fidelity of a proven model that works. We want the very best possible outcomes for people we have the honor to support toward an everyday life.

At The Copeland Center, we like to distinguish WRAP®’s meaning by emphasizing that we are “Recovering our Wellness” not recovering from an illness. As the acronym denotes, it is also a plan. It is a structured system that I develop for myself to take back control of my life and move toward a wellness goal. Perhaps I want to take back control of my life from unhealthy eating habits and move towards a healthier diet or a healthier weight – I can develop a WRAP® for that. Perhaps I want to take back control of my life from unemployment and move towards getting a job – I can write a WRAP® for that. Perhaps I want to discover a way to be happier and healthier in my everyday life – YES, I can write a WRAP® for that too. WRAP® is not a plan that I put on the shelf; WRAP® is a plan I put into action. WRAP® works if I work it; it doesn’t if I don’t.

One example of how I’ve used WRAP® in my own life, includes developing a plan to become a nonsmoker. When I was court-committed to a State Hospital, I didn’t get outside for almost 2 years because I wasn’t on a so-called privilege level. Then I found out that smokers, no matter what privilege level they were on got outside every 2 hours for two cigarettes. I could put two and two together and I started smoking. After 15 years of a pack of cigarettes a day, it became one of the hardest habits to break.

There are benefits to smoking, at least there were for me…I can name a few: 1) It lessened the noisiness in my head so I could focus outwardly on relationships. 2) It offered a purposeful pause to my life, making it easier to transition from one task or activity to the next. 3) It momentarily lessened boredom and eased anxiety.

When I decided to become a nonsmoker, I developed a WRAP® to quit smoking. First, I developed a list of Wellness Tools that would meet the same needs that smoking once met and Wellness Tools that were incompatible with having a cigarette. For example, you can’t take a shower and smoke at that same time; the first two months of becoming a nonsmoker, I was the cleanest person in the world. Rock climbing was a particularly helpful Wellness Tool because the left to right physical activity of climbing helped me to balance my left-right brain activity. I got to envision what I’d be like as a nonsmoker – the things I needed to do every day to control cigarettes so they didn’t control me and the things I might choose to do on occasion especially if

I was saving money becoming cigarette free. I recognized my Triggers and Early Warning Signs AND how I could take action using my wellness tools. I learn so much about myself – why I smoke and what I could do if I was choosing not to. As a reward for developing my WRAP® – I celebrated with two cigarettes. It is when I took personal responsibility for implementing my WRAP® and gathered supporters to encourage my journey – I was able to quit smoking.

WRAP® works when you live your self-determined plan.

WRAP® is also an evidence-based practice. WRAP® groups are co-facilitated by people living WRAP® in their own lives and who have taken the opportunity to complete a WRAP® Facilitators Course. This course is essential to the fidelity of WRAP® groups. Through training, co-facilitators experience living the values and ethics intra- and interpersonally.

I’m Matthew Federici and in 2010 I came to work for the Copeland Center for Wellness and Recovery as the executive director. Prior to this position, I had been on a journey that many of you have been on; from providing direct human services, management and then directing mental health programs. In this journey I was increasingly drawn toward programs and models based on individual strengths, practical approaches, and peer-to-peer models. When I signed up for a team working to transform Pennsylvania through the training and implementing of Peer Specialist, I met more and more people like Gina Calhoun.

Gina is a peer supporter, who was demonstrating that with the right opportunities, people considered to be in the “backwards” of institutions with little hope for recovery, can indeed succeed as full contributors in the community. Yet it was through the workshops on the Wellness Recovery Action Plan with Gina and other peer colleagues, side by side, that I found my voice, my story of wellness recovery.

Underneath my professional journey was a deep-seated belief in any individual’s potential for personal transformation because I had experienced it and witnessed firsthand. I had grown through times of near self-destruction. I grew with my family through times of mental health crisis. I visited my older brother in state hospitals and group homes. As a family, we recovered with a supportive community that never gave up hope, took responsibility, learned everything we could, advocated for our goals and found the peer support we needed. It wasn’t until attending my WRAP® workshop that I found a clear explanation of why my encounter and my brother’s encounter with the mental health system didn’t result in chronicity.

The Copeland Center’s work and Dr. Copeland’s initial research leading to the first WRAP® book validated the message of hope, self-efficacy, and personal empowerment. It validated messages that were just waiting to take root and expand in my professional

and personal life. My application of WRAP® started by illuminating my inner strengths and life lessons learned and today remains active to guide me in new personal bests in my wellness. Without my active use of WRAP® with peer support

I am convinced I would have burned out five times over by now.

The practice of WRAP® is expanding to support more and more people around more and more life issues. The most encouraging part for me is that this practice came from the people of our society who were written off as having the least insight into

recovery.

Highlighting the fidelity to values-based practices

As executive director, I have had the privilege to collaborate, network, and learn from likely close to a thousand people applying WRAP® in their own lives but also that are facilitating the application of WRAP® for thousands of other people. One of my consistent observations over the past 10 years is how the WRAP® Co-Facilitator course impacts our lives. A pre-requisite for this course is having learned and used our WRAP® so that we can build on that individual application and focus on critical values and practices in how we create a shared learning environment as co-facilitators.

Over the years, I have experienced and witnessed a key impact in learning these values and practices: a deepening understanding of how our WRAP® is not isolated to our personal, private life. Wellness recovery happens in relationships with others and is strengthened by an ongoing process of living with supporters whom we choose. A few of my favorite values and practices are focusing on strengths, placing no limits on recovery, focus on the mutual learning of peers working together and being the expert in our own life. These may give you a sense of the stark contrast to some traditional beliefs. However, it is not just a few that makes the environment so empowering to me - it is the synergy and totality of all the values and practices embraced by each diverse group that I see compelling people toward personal transformation.

I once had the pleasure to meet another great professional hero in my career, Dr. William Anthony, considered the founder of the Psychiatric Rehabilitation model out of Boston University. He pointed out to me that evidence-based practices are great

but how we will innovate and create evidence for new effective practices is not just doing the same old things. Instead, it is focusing on values-based practices.

When the values and practices are alive in the group, people begin to unleash the power within themselves, try new ways of thinking and behaving and move toward a life filled with self-determination, empowerment, self-advocacy and personal responsibility.

Testimonials 6

The value of WRAP® and the community around it is buried right in the title for me. Our world is full of problems and turmoil and it would be very easy to give in to despair faced with any one challenge. I learned in a Copeland Center refresher course last year that the sweet spot in the catastrophe is not in having the ability to solve the problems but in the empowerment of being able to take an action no matter how small that action seems. There is a force and energy that can be unleashed with the endless options of Wellness Tools being shared by the mutual learning in the workshops and the ones I have yet to create. For me, this is the true essence of the first key concept of Hope, the unlimited possibilities of approaching finding wellness in existence in my own unique way. (Eric, Peer Support Specialist, Pennsylvania)

When I started my recovery journey, I learned that I could have hope, and WRAP® was a major part of that hope. Through WRAP®, I first learned that I was an expert on myself, that I could have hopes and dreams, and that everyone deserved to be treated with dignity, compassion, and respect. I would have been the last person who would have thought that I would be where I am now, living a life, instead of just living. But WRAP® taught me that no matter what happens from day to day, I am able to control my thoughts and feelings about it. WRAP® has been there, through many challenges, and it's given me the ability to come through the other side of those challenges, stronger than I would have been before. I also found a community of the greatest people who are my evidence, every single day, who let me know that I can succeed at the things that I don't realize that I can do, yet. (Joseph, Peer Support Specialist, New York)

Learning about WRAP® was a life changer for me. It taught me to look deep inside myself, to recognize my strengths, put my own label to my name, and to raise my self-awareness by identifying all the difficulties that I face but with a plan to take action in overcoming and dealing with those difficulties when they arise. WRAP® taught me to see more to me than my story told, and gave me the tools to continue to improve to be the person who I know I really am. I would sit down for hours at a time, developing my WRAP®, learning about myself, and increasing my own awareness to both my good and bad traits. I spent time “experimenting,” you could say, on what worked for me, and what did not. I became aware that I really was the only expert on myself. WRAP® enlightened me to the idea that self-discovery and being my authentic self was possible. It helped me to find me. (Amey, Program Manager for a Peer-run Organization, Vermont)

WRAP® has been an influence in my life by sharing commonalities with other individuals and been the breaking point for me and my recovery to move forward with work again, leadership, faith, and trust in myself.

There are many reasons why I am where I am today in my life and the factors of WRAP® just in its name stands for, wellness recovery action planning - without wellness there is no recovery, no action, and definitely no planning. (Todd, Executive Director of a Peer-Run Organization, Iowa)

I am Sue Walther, the Executive Director of the Mental Health Association in Pennsylvania (MHAPA). I have held this position for more than 15 years. In my role as executive director, I oversee programs that provide navigation and advocacy for individuals seeking services and supports. In addition, I coordinate trainings and MHAPA’s public policy activities. I have been committed to reducing the stigma surrounding mental illness and to ensuring that everyone has the opportunity to live in the community of their choice.

During my association with MHAPA, I have witnessed a revolution in the mental health system. There is still work to be done, but in my time the system has gone from a medical to a recovery model; it has changed from institutional based to community focused; it is shaped in true partnership with consumers and their families; and finally, it is based on wellness and strengths not illness and weaknesses. We owe a debt of gratitude to individuals and their families with lived experience who were willing to speak out strongly and frequently to ensure a system that works for the individual. Those courageous folks shaped my career at MHAPA and I am forever thankful.

SAMHSA defines recovery as a process of change through which individuals improve their health and wellness, live a self-directed life, and strive to reach their full potential. One of the recovery tools to assist individuals in their journey is a mental health advance directive.

In 2004, Pennsylvania enacted legislation (Act 194) that provides the opportunity for individuals living with mental illness to create a Mental Health Advance Directive (MHAD) and plan ahead for mental health services and supports in the event they become unable to make decisions for themselves. A MHAD offers a clear written statement of an individual’s mental health treatment preferences or other expressed wishes or instructions should they become incapacitated. It can also be used to assign decision-making authority to another person who can act on that person’s behalf during times of incapacitation.

MHADs offer several key benefits. Correctly implemented and executed, they can:

-

Promote individual autonomy and empowerment in the recovery from mental illness;

-

Enhance communication between individuals and their families, friends, healthcare providers, and other professionals;

-

Protect individuals from being subjected to ineffective, unwanted, or possibly harmful treatments or actions; and

-

Help in preventing crises and the resulting use of involuntary treatment or safety interventions such as restraint or seclusion.

Components of a mental health advance directive include the specific intent to create a document that allows for advance mental health care decision making; specific instructions about preferences for hospitalization and alternatives to hospitalization, medications, electroconvulsive therapy, and emergency interventions and participation in experimental studies or drug trials; instructions about who should be notified if and when the person is admitted to a psychiatric facility; and also instructions on who should have temporary custody of minor children or pet.

References

- Copeland Center for Wellness and Recovery. (2014). The Way WRAP® Works! Strengthening Core Values and Practices. https://copelandcenter.com/resources/way-WRAP®-works

- Copeland, M., Cook J., & Razzano, L. (2010). Wellness Recovery Action Plan: Application to the National Registry of Effective Programs and Practices. Chicago, IL: University of Illinois at Chicago Center on Mental Health Research and Policy.

- Wellness Recovery Action Plan, Updated Edition (Human Potential Press, Revised 2018)

- National Registry of Evidence-Based Programs and Practices. (2013). Wellness recovery action plan. Washington, DC: Author. Retrieved from http://nrepp.samhsa.gov/ViewIntervention.aspx?id=208.

- Cook, J.A., Copeland, M.E., Jonikas, J.A. et al. (under resubmit). Results of a randomized controlled trial of mental illness self-management using Wellness Recovery Action Planning. Schizophrenia Bulletin.

- Federici, M. R. (2013). The importance of fidelity in peer-based programs: The case of the Wellness Recovery Action Plan. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 36(4), 314-318.

Biographies

Gina Calhoun: Certified Peer Specialist, Educator and Program Director for the Copeland Center for Wellness and Recovery. gcalhoun@copelandcenter.com

Matthew Federici: Executive Director and International Speaker for the Copeland Center for Wellness and Recovery. mfederici@copelandcenter.com

Sue Walther: Advocate for Human Rights and the Executive Director of the Mental Health Association in Pennsylvania. swalther@mhapa.org

Contacts

Gina Calhoun

Matthew Federici

Sue Walther

J. Rachel Krouse, Kathleen E. Ammerman, Zachary L. Ulisse, and Timothy J. Runge | 28-46

Volume 8 ► Issue 3 ► 2019

School-Wide Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports: A Promising Framework to Reduce Exclusionary Practices and Placements

J. Rachel Krouse, Kathleen E. Ammerman, Zachary L. Ulisse, and Timothy J. Runge

Abstract

School-wide positive behavioral supports and interventions (SWPBIS) is a comprehensive approach to addressing the social, emotional, and behavioral health of all students. Data from schools affiliated with the Pennsylvania Positive Behavior Support Network were analyzed to determine the extent to which SWPBIS is associated with reductions in restrictive disciplinary and educational-placement practices. High schools implementing SWPBIS reported significantly lower out-of-school suspensions over time. Further, results suggest that SWPBIS is associated with reductions in out-of-school placements for all student and students with emotional disturbance.

Introduction

Positive Behavior Supports is a broad term that defines an array of approaches designed to create changes in social behaviors that facilitate access to various ecologies.1 When applied in school settings (i.e. kindergarten through 12th grade), it is commonly referred to as School-Wide Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports (SWPBIS). SWPBIS is a multi-tiered system of behavioral supports that employs evidence-based prevention and intervention strategies throughout all ecologies of a school 2 to support the behavioral, social, and emotional development of all students. SWPBIS can also create a more inclusive environment for students with disabilities.

There are three tiers within SWPBIS, termed tier 1 (primary), tier 2 (secondary), and tier 3 (tertiary). Tier 1 SWPBIS includes the assessment and instructional practices provided to all students to prevent or minimize barriers to learning while concurrently promoting inclusive educational practices for all students. 3 Additional assessments, interventions, and supports beyond the primary tier are required by approximately 15% – 30% of the school population. 4,5 These additional assessments, interventions, and supports are known as tier 2 SWPBIS. If students do not respond positively to the tier 1 or tier 2 interventions and supports, they are then provided tier 3 interventions and supports. This applies to approximately 5% – 10% of the students. Eber and colleagues 6 describe these services as student-centered and family-oriented given that there are often significant needs that extend across all the students’ ecologies.

There is growing evidence that SWPBIS is associated with positive outcomes for students, staff, and schools. For example, Lassen, Steele, and Sailor 7 found that adherence to SWPBIS procedures was significantly correlated with decreases in problem behaviors exhibited by students. When students display significant behavioral disruptions in the school environment, typically an office discipline referral (ODR) is issued. The empirical evidence regarding the extent to which SWPBIS implementation is related to decreases in ODR is robust. Flannery et al. 8 found a negative correlation between fidelity and ODRs in 12 high schools. Specifically, when the extent to which SWPBIS was implemented as prescribed (i.e., fidelity) increased, office disciplinary referrals significantly decreased.

Another indicator of discipline challenges in school settings is the occurrence of out-of-school suspensions (OSS) which often are the result of either a student’s chronic misbehavior in school or exhibition of extremely dangerous or illicit behavior. As is the case with ODRs, the empirical literature regarding SWPBIS and OSS is growing. Gage, Grasley-Boy, George, Childs, and Kincaid 9 found that high fidelity implementation of SWPBIS resulted in fewer OSS, particularly for students with disabilities and students of color. Thus, SWPBIS is an encouraging framework for reducing chronic and dangerous behavior for populations that are historically at risk for school failure.

Given the national evidence regarding the association of SWPBIS and reductions in OSSs, it was hypothesized that similar reductions in exclusionary disciplinary practices would be observed in data from Pennsylvania. Specifically, our first empirical question was to appraise the extent to which SWPBIS is associated with changes in OSS.

SWPBIS promotes implementation of evidence-based supports and practices across all settings, not limited to just the special education classroom. Consequently, Freeman and colleagues 10 hypothesized that SWPBIS: (a) creates environments in which all educators are equipped with the skills and resources to support the complex needs of students with disabilities in general education settings; and (b) students with disabilities can be included more with non-disabled peers as a direct result of increased skills of all educators and supports embedded within general education settings. Therefore, the extent to which SWPBIS is associated with providing the practices and supports necessary to educate students with disabilities in their least restrictive environment (LRE) was of interest and constituted our secondary empirical inquiry.

Relatedly, some students present with such significant academic, social, emotional, and/or behavioral needs that highly specialized and intensive services are necessary to help them maximally benefit from instruction. For some of these students,

their neighborhood school does not have the resources to provide the specialized and intensity of services they need. Consequently, out-of-school placements (OSP) are sometimes recommended. OSPs are a broad set of options available to

schools, families, and students, including non-neighborhood public schools, private schools, day-treatment centers, public and private residential facilities, homebound instruction, or instruction within a hospital setting. Leaders in SWPBIS

have articulated that reducing OSPs was one of the primary motivations for its development and implementation over two decades ago. 10,3 It is hypothesized that implementation of the multi-tiered SWPBIS framework may reduce the need for

OSPs, especially for students whose primary needs are focused on social, emotional, and / or behavioral functioning. This was our third line of inquiry.

Method

Data from the Pennsylvania Positive Behavior Support (PAPBS) Network database were analyzed to test these hypotheses. Briefly, the PAPBS Network includes affiliation of over 1,000 schools in Pennsylvania. Fidelity of implementation of

tier 1 SWPBIS and various student- and school-level outcomes are monitored annually by the Pennsylvania Department of Education. Data are voluntarily submitted by participating schools to a secure website. Data are then released by Pennsylvania

Department of Education to the research team at Indiana University of Pennsylvania per its Institutional Review Board for the Protection of Human Subjects approval. Because of the voluntary nature of data submission, not all schools regularly

submit fidelity of implementation and / or complete outcome data. As of spring 2019, 565 schools were implementing tier 1 SWPBIS with fidelity. The number of schools submitting partial or complete outcome data varies from one year to the

next and by outcome measure reported.

Out-of-School Suspensions

National data indicate out-of-school suspensions (OSSs) are used at statistically significant lower rates in elementary schools compared to secondary schools. 9,11 Therefore, PAPBS Network data were dichotomized into elementary and secondary

schools. Initial analyses of OSS data indicated that elementary schools consistently reported statistically significantly lower OSS rates than secondary schools (i.e., middle, junior/senior, and high schools), therefore subsequent analyses were

conducted separately for elementary and secondary schools.

Elementary Schools

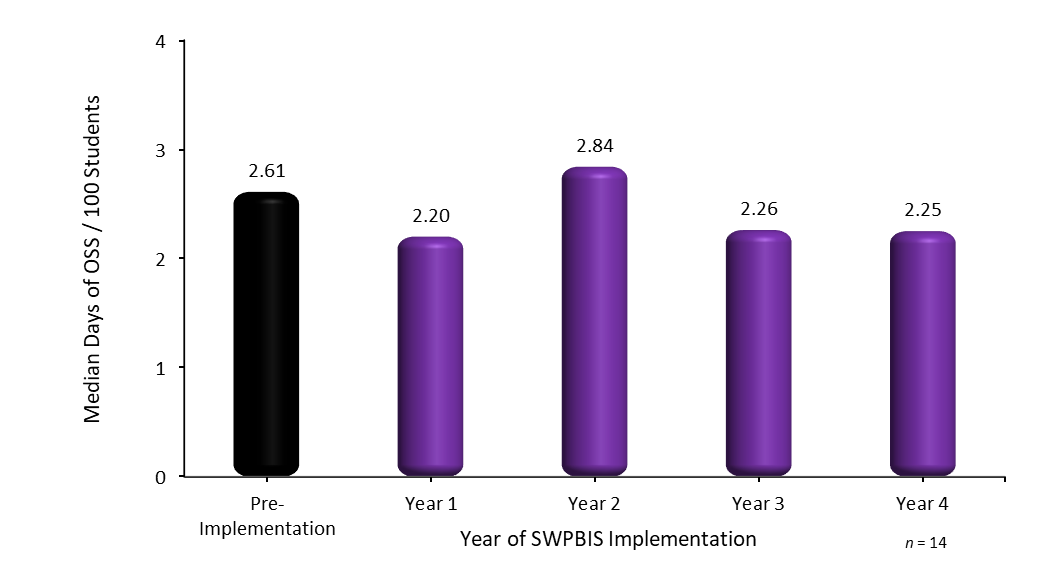

A series of Friedman tests were conducted to assess whether OSS rates prior to tier 1 SWPBIS implementation changed once the framework was adopted. These non-parametric equivalents to the repeated-measures ANOVA are reported given violations of normality in the data; however, repeated-measures ANOVAs were also conducted for each analysis, producing identical results. In every instance, tier 1 SWPBIS was not associated with statistically significant changes in OSS rates across pre-implementation to multiple years of implementation. A longitudinal review of pre-implementation to the fourth year of tier 1 SWPBIS implementation is provided in Figure 1. For these 14 elementary schools, the OSS rates did not statistically change across any of the years of tier 1 SWPBIS compared to pre-implementation levels, X2(4) = 3.799, p = .434. Readers are cautioned that these data represent medians, not means; therefore, normative comparisons of OSS rates to national trends are inappropriate.

Figure 1. Annual Median OSS Days Served per 100 Students in Elementary Schools Pre-Implementation to Year 4

Note. OSS = out-of-school suspension; median OSS rates did not significantly change from one year to another.

Secondary Schools

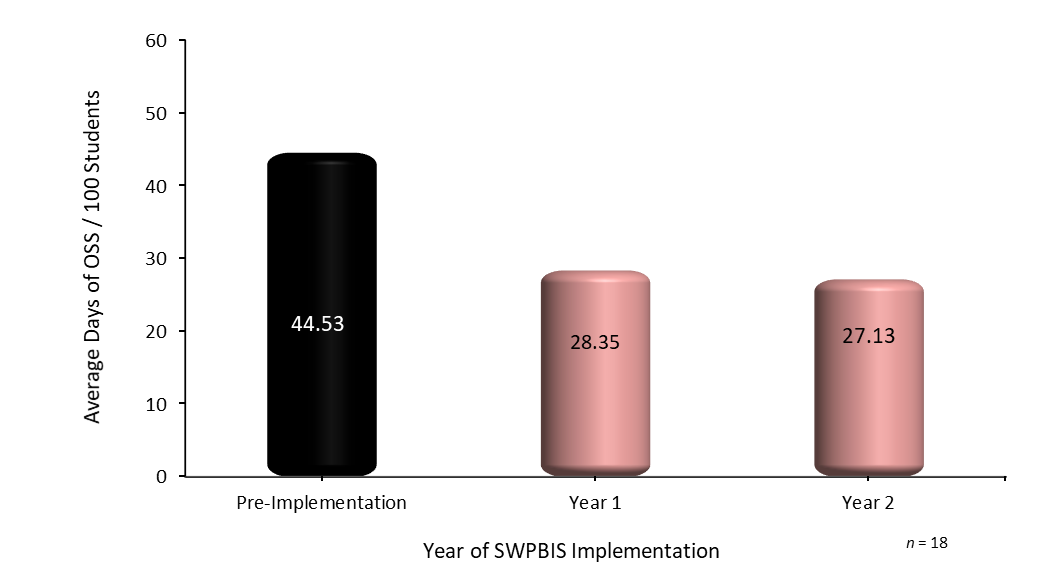

Parametric statistical analyses were conducted with secondary school data given that assumptions of these procedures were all met. Non-parametric equivalent procedures were also employed as confirmation, although these results are not presented here. As displayed in Figure 2, OSS rates statistically significantly declined across pre-implementation to year 2 of tier 1 SWPBIS, F(3, 24) = 3.719, p = .025, for a group of 18 secondary schools. Inspection of the pairwise comparisons, via Bonferroni post hoc tests, indicated that the greatest decline in OSS rates was from pre-implementation to year 1, representing an initial 36% reduction in OSS rates in the first year of Tier 1 SWPBIS. OSS rates from year 1 to year 2 remained statistically similar.

Figure 2. Longitudinal Average OSS Days Served per 100 Students in Secondary Schools from Pre-Implementation to Year 2

Note. OSS = out-of-school suspensions. OSS rates statistically significantly declined from pre-implementation to year 1 and remained statistically similar from year 1 to year 2.

Similar reductions in the first year of tier 1 SWPBIS adoption followed by sustained OSS rates in subsequent years were noted in analyses of longer duration (e.g., pre-implementation to year 3), although those analyses were based on small sample sizes.

For example, a 5-year longitudinal analysis of 10 secondary schools that supplied pre-implementation and year 4 fidelity and OSS data (but not necessarily complete data during the interim years) was also statistically significant, t(9) = 2.649,

p = .027.

Least Restrictive Environment

Schools submit the number of students who are educated in three state-defined categories of LRE. These categories are based on the proportion of time a student with a disability is educated with non-disabled peers. The three categories are: (a) ≥80% of the school day in a general education classroom; (b) 40-79% of the school day in a general education classroom; and (c) <40% of the school day included with non-disabled peers. Data on the proportion of students with disabilities educated in the three respective LRE categories were used in the analyses.

The first empirical inquiry for LRE focused on whether the LRE indices varied as a function of building type. A series of ANOVAs with applicable Bonferroni post hoc analyses were conducted at pre-implementation and each subsequent year of SWPBIS implementation to evaluate the extent to which LRE indices differed by elementary, middle, K-8, junior / senior, and high schools. Overall, none of the F tests or post hoc analyses were statistically significant, indicating that LRE indices are comparable across building types. Therefore, data were aggregated across elementary, middle, K-8, junior / senior, and high schools.

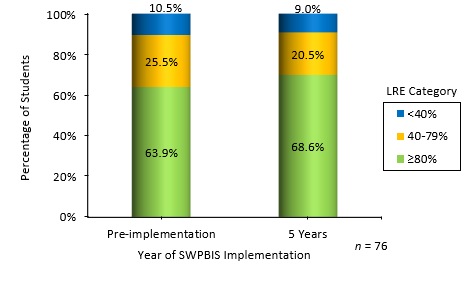

For schools that submitted both fidelity and outcome data, a series of pre-post comparisons were conducted to analyze differences in LRE placement across multiple years of SWPBIS implementation. These analyses suggest that the most inclusive categories of LRE placement (proportion of students in the ≥80% and 40%-79% of the school day educated in regular education setting categories) did not significantly change over multiple years of implementation; however, the results also suggest that the most exclusive category of LRE (<40% of the school day spent in a regular education setting) decreases after multiple years of SWPBIS implementation. For example, there was a statistically significant decrease in the proportion of students educated in the most restrictive environment starting two years after implementation, and this reduction continued to occur until year 5 post-implementation. A visual display of these results is presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Longitudinal LRE Percentages

Note. The percentage of students in the ≥80% LRE index did not statistically change by Year 5; the percentage of students in the 40-79% LRE index did not statistically change by Year 5; the percentage of students in the <40% LRE index statistically

significantly decreased by Year 5.

Out-of-School Placements

OSPs were operationalized as the rate of OSP for all students per 100 students enrolled in the school and the rate of OSP for students identified as emotionally disturbed per 100 students enrolled. A series of ANOVAs with Bonferroni post hocs were conducted using cross-sectional data to evaluate the extent to which tier 1 SWPBIS is associated with changes in OSPs. Kruskal-Wallis H tests were conducted as well given the violation of the normality assumption of the ANOVA, although the results were similar to the parametric tests and are thus not reported here.

Across pre-implementation and multiple years of SWPBIS and across all OSP metrics, elementary schools were statistically similar to middle and K-8 schools. For example, the mean rate of placing any student in an OSP in the year prior to SWPBIS implementation

was statistically similar, F(2, 153) = 0.826, p = .440. The mean rate of placing students identified as emotionally disturbed in OSP was also statistically similar in the year prior to SWPBIS implementation, F(2, 150) =

2.581, p = .079. Similarly, elementary, middle, and K-8 schools in their first year of SWPBIS were statistically similar in their OSP rates for all students, F(2, 204) = 0.752, p = .473, and in their OSP rates for students

identified as emotionally disturbed, F(2, 210) = 2.405, p = .093. This pattern of similar results across elementary, middle, and K-8 persisted in subsequent years of SWPBIS implementation to at least the fifth year of SWPBIS at

which time sample sizes became too small to test for differences.

For many, but not all, of the years of implementation and OSP outcomes, high schools were statistically significantly different from elementary, middle, and K-8 schools. For example, high schools (M = 4.85 per 100 students) used OSPs with

all students at statistically significantly higher rates than elementary, middle, and K-8 schools (M = 1.37 per 100 students) in the year prior to SWPBIS implementation, t(182) = -4.629, p = .000. High schools also used

OSPs with students identified as emotionally disturbed (M = 1.24 per 100 students) at statistically significantly higher rates than elementary, middle, and K-8 schools (M = 0.404 per 100 students), t(178) = -4.695, p =

.000, during the year prior to SWPBIS implementation. Similar statistically significant differences were found in the other years of SWPBIS implementation, although results are not presented here. Therefore, subsequent OSP analyses were

completed on elementary, middle, and K-8 schools separately from high schools.

Elementary, Middle, and K-8 Schools

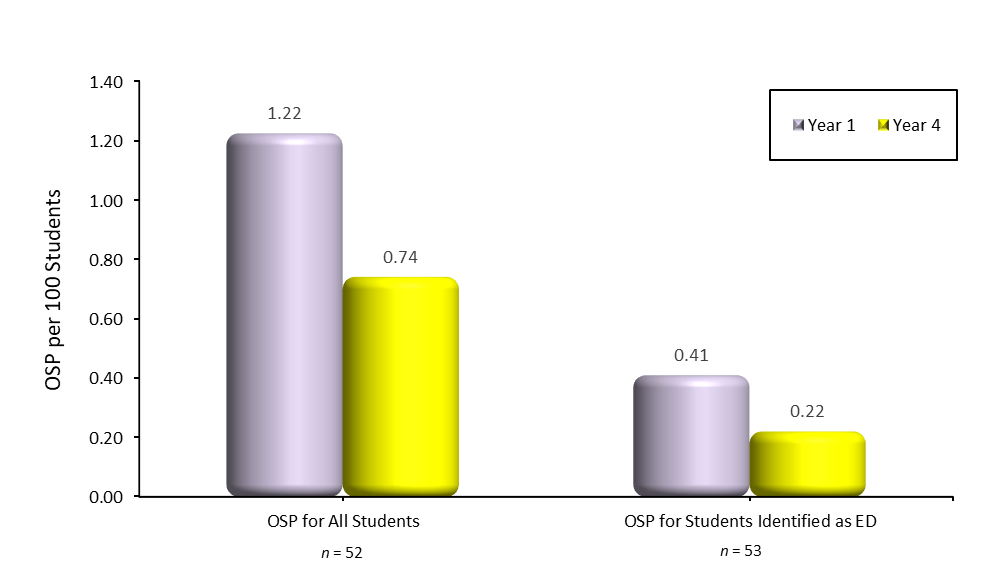

Longitudinal OSP rates for all students and students identified as emotionally disturbed submitted by schools implementing SWPBIS for one to four years are presented in Figure 4. Importantly, pre-implementation OSP rates are not presented in these

results. Paired-samples t-tests revealed that OSP rates for all students statistically significantly declined from year 1 to year 4, t(51) = 2.148, p = .036. OSPs for all students dropped from an average of 1.22 OSPs per

100 students in year 1 to an average of 0.74 OSPs per 100 students in year 4. Similarly, OSP rates for students identified as emotionally disturbed approached statistically significant mean differences from year 1 to year 4, t(52) = 1.937,

p = .058. OSPs for students identified as emotionally disturbed dropped from an average of 0.41 per 100 students in year 1 to an average of 0.22 per 100 students in year 4.

Figure 4. Longitudinal Analysis of Out-of-School Placements for All Students and Students with Emotional Disturbance per 100 Students for Elementary, Middle, and K-8 Schools After SWPBIS is Adopted

Note. OSP = Out-of-School Placement; ED = emotional disturbance. OSP for all students and for students identified as emotionally disturbed were statistically significantly lower at the fourth year of SWPBIS compared to the first year

of SWPBIS.

High Schools

An insufficient number of high schools submitted complete fidelity and OSP data to permit data analyses to be conducted. Further, reporting of the few high schools that did submit these data would violate the schools’ promised confidentiality.

Therefore, these data will be monitored in future years in the hope that more robust amounts of data will be available to review and report.

Discussion

SWPBIS is viewed as a promising school reform framework to address, among many things, exclusionary practices for students with social, emotional, and behavioral challenges. Data from the PAPBS Network indicate that SWPBIS is associated with a number of positive outcomes for all students, and in particular, students with disabilities. Specifically, these findings suggest that SWPBIS is associated with statistically significant reductions in OSS in secondary schools. Such reductions appear to occur within the first year of SWPBIS implementation. Similar reductions in OSS were not observed in elementary schools, although it is noted that OSS rates in PAPBS Network elementary schools are very low anyway. Still, reductions in elementary schools’ use of OSS would be ideal.

Data from PAPBS Network schools suggests a statistically significant association between SWPBIS implementation and reductions in the most restrictive educational placement for students with disabilities. This conclusion is made with considerable caution, however, for a number of reasons. First, SWPBIS alone is likely not the sole impetus of reductions in restrictive placements, particularly given that most students with special education needs require substantial academic support. It is likely that SWPBIS is a necessary, but insufficient, framework to promoting more inclusive practices for all students with special needs. Further, considerable work has occurred across Pennsylvania and the nation to promote other inclusive practices, including standards-based education and use of empirically-supported curriculum that employ evidence-based instructional practices, which likely result in more inclusive educational placements for students with disabilities. Therefore, the apparent reductions in the most restrictive education placement in the data reported in this study are likely due to a number of factors, with SWPBIS contributing only a small amount toward more inclusive practices. Despite this caution, it is encouraging to observe more inclusive practices in SWPBIS schools.

Finally, these data suggest that SWPBIS is, at least in part, associated with reductions in OSPs for all students and students with a primary classification of emotional disturbance. Such findings appear to support the contention made by Freeman

and colleagues 10 that SWPBIS will create environments that are more supportive of students’ needs. This conclusion, as with the previous conclusions, is made cautiously given these preliminary findings. Replication of results

with larger sample sizes is necessary before stronger conclusions can be made.

Limitations

The first limitation to these findings is the lack of a control group to compare with SWPBIS schools. This methodological limitation was partially addressed via longitudinal analyses whereby schools served as their own control. Future work

must include control groups, however, to mitigate the potential influence of time and the social milieu that is lost when aggregating data over the 10-year period of this project. Another limitation of this study includes the abnormality of

the data in some of the analyses. When reviewing OSS data, most schools engage in these practices infrequently. There are a handful of schools, however, that administer these types of disciplines very frequently. This skews the data

distribution and thus makes it difficult to find any significant results. This limitation was partially addressed by employing non-parametric data analytic procedures and using parametric equivalents as validation. Also, the relatively

small sample size of schools that submitted data was a limitation. As was noted earlier, 565 schools have achieved full implementation of tier 1 SWPBIS; however, a very small proportion of those schools submitted complete data for the analyses

reported in this study. It is possible that a bias exists in the dataset where only those schools that achieved positive outcomes voluntarily submitted their data. Conversely, a school that did not achieve desirable outcomes might withhold

its data, thus resulting in a biased dataset with which to conduct data analyses.

Future Study

As more schools begin to reach full fidelity and submit data for all three tiers of SWPBIS, future studies can be conducted on these larger samples using the same methodology. Also, different SWPBIS procedures can be looked at more closely and compared across different schools. For example, are there certain SWPBIS practices or procedures that are different across certain schools which may help explain the differences in utilization of OSS? Are there certain practices that influence the tendency for certain schools to be more inclusive in terms of LRE? These, and other important questions, will continue to shape the practice of developing educational environments that meet the needs of all students.

References

- Kincaid, D., Dunlap, G., Kern, L., Lane, K. L., Bambara, L. M., Brown, F.,…Knoster, T. P. Positive behavior support: A proposal for updating and refining the definition. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions. 2016; 18: 69-73. doi: 10.1177/1098300715604826

- Algozzine, B., Barrett, S., Eber, L., George, H., Horner, R., Lewis, T., & Sugai, G. School-wide PBIS tiered fidelity inventory. Eugene, OR: National Technical Assistance Center on Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports. Retrieved from www.pbis.org. 2014.

- Sugai, G., & Horner, R. H. Schoolwide positive behavior support. In W. Sailor, G. Sugai, G. Dunlap, and R. Horner (Eds.). Handbook of positive behavior support. New York, NY: Springer Science + Media; 2009: 307-326.

- Gottfredson, G. D., & Gottfredson, D. C. A national study of delinquency prevention in schools: Rationale for a study to describe the extensiveness and implementation of programs to prevent adolescent problem behavior in schools. Ellicott City, MD: Gottfredson Associates; 1996.

- Walker, H. M., Ramsey, E., & Gresham, F. M. Antisocial behavior in schools: Evidence -based practices (2nd ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth / Thomson Learning; 2005.

- Eber, L., Hyde, K., Rose, J., Breen, K., McDonald, D., & Lewandowski, H. Completing the continuum of schoolwide positive behavior support: Wraparound as a tertiary-level intervention. In W. Sailor, G. Sugai, G. Dunlap, and R. Horner (Eds.). Handbook of positive behavior support (pp. 671-704). New York, NY: Springer Science + Media; 2009.

- Lassen, S., Steele, M., & Sailor, W. The relationship of school‐wide Positive Behavior Support to academic achievement in an urban middle school. Psychology in the Schools. 2006; 43: 701-712. doi: 10.1002/pits.20177

- Flannery, K. B., Fenning, P., McGrath Kato, M., & McIntosh, K. Effects of school-wide positive behavioral interventions and supports and fidelity of implementation on problem behavior in high schools. School Psychology Quarterly. 2014; 29: 111-124. doi: 10.1037/spq0000039

- Gage, N. A., Grasley-Boy, N., George, H. P., Childs, K., & Kincaid, D. A quasi-experimental design analysis of the effects of school-wide positive behavior interventions and supports on discipline in Florida. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions. 2019; 21: 50-61. doi: 10.1177/1098300718768208

- Freeman, R., Eber, L., Anderson, C., Irvin, L., Horner, R., Bounds, M., & Dunlap, G. Building inclusive school cultures using school-wide pbs: Designing effective individual support systems for students with significant disabilities. Research & Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities. 2006; 31: 4-17. doi: 10.2511/rpsd.31.1.4

- Spaulding, S. A., Irvin, L. K., Horner, R. H., May, S. L., Emeldi, M., Tobin, T. J., & Sugai, G. Schoolwide social-behavioral climate, student problem behavior, and related administrative decisions: Empirical patterns from 1,510 schools nationwide.

- Journal of Positive Behavior Intervention. 2010; 12: 69-85. doi:10.1177/1098300708329011 School-Wide Information System. SWIS summary. Eugene, OR: Educational & Community Supports. Retrieved from pbisapps.org; 2017.

Biographies

J. Rachel Krouse, M.Ed., is a third-year doctoral student currently enrolled in the Indiana University of Pennsylvania School Psychology PhD program. She has been involved with School-Wide Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports research for more than two years.

Kathleen E. Ammerman, M.Ed., is a third-year doctoral student currently enrolled in the Indiana University of Pennsylvania School Psychology PhD program. She has been involved with School-Wide Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports research for more than two years.

Zachary L. Ulisse, M.Ed., is a second-year doctoral student currently enrolled in the Indiana University of Pennsylvania School Psychology PhD program.

Timothy J. Runge, PhD, NCSP, BCBA is a Professor and Chair of the Educational and School Psychology Department at Indiana University of Pennsylvania. He has more than 20 years of experience implementing, consulting, and conducting research on School-Wide Positive Behavioral Interventions and Support.

Timothy J. Runge, PhD, NCSP, BCBA,

Indiana University of Pennsylvania,

1175 Maple Street, Stouffer 246C,

Indiana, PA 15705O'Brien | 47-54

Volume 8 ► Issue 3 ► 2019

Fair and Prudent Risk

John O’Brien

Introduction

When Bob Perske introduced the concept of dignity of risk he intended “to illustrate [with practical examples] that there can be such a thing as human dignity in taking risks, and there can be a dehumanizing indignity in safety” 1. The risks he has in mind are far from trivial. In a discussion of dignity of risk for parents, Perske,2 among less extreme examples, itemizes a mother’s memorial to her son with Down syndrome who died trying to save his brother in a house fire; an account of five group home residents and a staff person who drowned while trying to save swimmers caught in an undertow; and German institution residents who, for a time, outwitted and then faced, with dignity, agents of the Nazi euthanasia program whose grey vans prototyped a means of mass killing.

Perske makes five arguments, paraphrased here, which are relevant today.

-

No matter the motivation, imposing unnecessary avoidance of risk degrades human dignity, reinforces prejudiced beliefs and deprives people of opportunities to show courage and develop their capabilities.

-

There is great developmental power when high expectations and mindful supports encourage accepting the risks that accompany the pursuit of a person’s purposes.

-

Determining whether a risk is fair and prudent is a matter of judging the likely fit between a particular person’s capabilities and protections and the foreseeable demands of specific circumstances.

-

Judgement of the fairness and prudence of a risk can be skewed by underestimation of people’s capabilities and courage in the face of actual risk and their resilience to adverse experiences given good support.

-

Bias toward underestimating a person and risk avoidance can be mindless, built-in to internalized beliefs, taken-for-granted routines and policies, structures, and culture.

Competing Goods

Retrieving these foundations regarding the idea of dignity of risk matters because the changes that occurred in the 50 years since Perske’s writing have sharpened conflict between the pursuit of different positive ideologies. The field has never been so certain of people’s right to choose. The first General Principle in The UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities is, “Respect for inherent dignity, individual autonomy including the freedom to make one’s own choices, and independence of persons.”3 Also, the domain of service provision has never been so concerned with assessing, preventing and managing risk. At its best, this concern actively promotes safety and health, and anyway it related efforts to comply with regulations and to minimize liability. Efforts to dissolve the conflict by subordinating one good to the other are unsatisfying. Neglecting concern for health and safety opens the way to avoidable harm; asserting the supremacy of others’ judgments about health and safety insults dignity and stifles development. Without thoughtful deliberation grounded in particular circumstances, risk avoidance is favored because it is the simpler solution.

Rising consciousness of the ways in which services to people with intellectual disabilities (ID) and autism historically been offered via power exercised over these often socially excluded people requires reflection and re-examining our thoughts about

risk. Service workers not only have the power to make decisions about risk, they, along with policy makers, also control the assistance available to support people’s efforts to discover and pursue valued social roles. Ethical service providers

and policy makers realize they are accountable for any power inequality that might shape what they offer those who count on their services.

Prudence Shows the Way

Perske shows the way forward in his choice of modifiers for the risk he advocates. Risk, he says, must be prudent and decisions about limiting freedom in order to decrease the chances of risk must be made fairly.

Fair deliberations lead to action that considers both the right to risk and the right to safety and health as each individual exercises their freedom to pursue what matters to them in a specific situation. Prudence – the virtue of choosing the right means to good ends under conditions of uncertainty4– guides fair deliberations. In English, prudence has acquired a shadow of caution and risk avoidance. The Latin translation of a key word in Greek philosophy provides a better understanding of its power. In this usage, prudence means “practical wisdom” (the Greek in Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics is pronēsis).

Practical wisdom is the art of realizing general principles in particular circumstances. Prudence moves beyond the binary, “either risk or safety; autonomy or health,” into a socially creative space, “both risk with safety; development of capacity for wise choice”. Prudence doesn’t debate generalities, “Does Susan have the right to attend next week’s church revival?” Neither does it indulge in escaping the creative potential in uncertainty with pre-emptive judgements, such as “The crowd’s emotional excitement will overstimulate Susan and result in unsafe behavior.” Practical wisdom inquires, “How can Susan have the best possible chances to get what she wants from participating in this specific church event? Where can we foresee breakdowns and what combination of accommodation and assistance provides the best odds of preventing, repairing or retreating from them? Together how might we provide or arrange the required support for her.”

Those who have a say in determining acceptable risk have different perceptions of what is dangerous and what limitations are acceptable. Fair deliberations of these differences have preconditions. A fair deliberation is demanding. It calls for grounded inquiry into varying assumptions about danger and active exploration of possibilities for deploying creative support. Practical wisdom takes into account the person’s current capabilities and vulnerabilities, the likely protections and challenges in the situation the person wants to navigate, and the competence of available support. All of these considerations happen under uncertainty: it’s not possible to predict with complete confidence how a future event will play out and how a person will respond. In the event some people melt down in unpredicted ways; others show abilities no one has seen before. Uncertainty can draw the imagination toward the negative, if not catastrophic, “what-ifs”. Low probability losses claim more energetic attention than more likely rewards.5

When the process for deliberating on risk is sufficient, the person themselves is as active a participant as the competence of the rest of the others involved can support. The

individual should be engaged in decision making and in assessing the situation, generating ways to address potential risks, and deciding on a course of action along with support staff. Others actively involved in deliberation should know

the person in a way that gives them a reliable sense of the whole person, including their purposes and preferences as well as their specific vulnerabilities and the impact of their impairments in different life situations. A strong person-centered

planning process clarifies what matters to the person and develops a team able to creatively negotiate differences. When something matters to a person, oftentimes decision-makers have a bias toward doing what it takes to get to yes. Sometimes

professional team members who know the person less well, or managers who know about a person from other’s verbal or written accounts, assume responsibility for pronouncing on questions of risk. A competent supports team deliberates, listens,

raises facilitating questions, and encourages creative responses and prudent decision-making and is made up of those with strong personal connections and day-to-day interactions with the individual who wishes to pursue a potential/perceived risk.

Confidence in the competence, commitment, and relationship continuity of the direct support workers whose assistance the person will rely on in a potentially risky situation reduces uncertainty. There is more room for risk when people and direct support

workers have built trust through shared experiences. There is more room for risk when those who support a person have personal knowledge of what could challenge that person and what is likely to work to recover from unsafe occurrences or breakdowns

in participation. There is more room for risk when direct support workers can draw on past experience in accompanying a person into new experiences to decide when to stay in the background and when and how to step forward.

Organizational Accountability for Power Over People

Organizations have a responsibility to continually improve their capacity to underwrite risk in ways that give increasing scope for pursuit of a person’s purposes or expression of their preferences. One aspect of this responsibility commits an organization

to continually transforming its resources into forms that offer effective support for full, individual participation in community places of interest to the person.

6 When an organization accepts this responsibility, decisions that result in limiting a person’s choice are studied for what they reveal about opportunities to improve individualized supports. Staff schedules that limit support for

night time activities may rule a particular situation too risky. A responsible organization follows this conclusion with a search for better organization of support so that this cause of limitation will have less influence in the future.

A related responsibility encourages organizations to raise consciousness of mindsets that make limiting people’s freedom in the name of protection an unquestioned routine. Culture – our collective and usually unexamined take on “the way it is”– remains unfriendly to expanding the freedom of people with ID and developmental disabilities (DD). Yet people with ID/DD have the right to choose. The expectation of compliance still frames life for most people with ID/DD. An enduring presumption of incompetence disposes courts to routinely grant guardianship, extinguishing legal personhood. A service client is often expected to obey those who “know what is best,” even when those deemed to “know best” come fresh from new staff orientation. As a requirement of public funding for services, people comply with detailed specifications about how they will live, who may assist them, and what support personnel can do. Those placed in group settings live with more constraining norms and structures than people who live with adequate individualized supports. Systemically, the underestimation of developmental potential is common and too often internalized by people with ID/DD.

Deliberations about risk are a site for mindful resistance to the assumption of power over people with ID/DD. Organizations stretch to improve their capacity to offer good support in uncertain circumstances and to include people with ID/DD in deliberations

that take their will and preference seriously. Those assessing risks do not take decisions lightly because they realize that even necessary limitations of risk can deprive a person of their rights and compromise their dignity.

References

- Perske R. Dignity of risk and the mentally retarded. Mental Retardation 1972; : 10(1), 24-27. Retrieved from www.robertperske.com/Articles.html.

-

Perske, R. New directions for parents of persons who are retarded. Nashville: Abingdon Press; 1973.

-

United Nations Convention on the rights of persons with disabilities. 2006. Retrieved from https://www.un.org/esa/socdev/enable/rights/convtexte.htm

- Comte-Sponville A. Petit traitté de grandes vertus. Paris: Universitaires de France; 1996.

-

Thaler R, Tversky A, Kahneman D & Schwartz A. The effect of myopia and loss aversion on risk taking: An experimental test. The Quarterly Journal of Economics,1997; 112 647-661

- O’Brien J. & Mount B. (2015). Pathfinders: People with developmental disabilities and their allies building communities that work better for everyone. Toronto: Inclusion Press; 2005. https://bit.ly/2K5V5KR

Biography

John O’Brien learns about building more just and inclusive communities from people with disabilities, their families, and their allies. He uses what he learns to advise people with disabilities and their families, advocacy groups, service providers, and governments and to spread the news among people interested in change by writing and through workshops. He works in partnership with Connie Lyle O’Brien and a group of friends from 18 countries.

He is a Fellow of the Centre for Welfare Reform (UK) and is affiliated with the Center on Human Policy, Law & Disability, Syracuse University (US), in Control Partnerships (UK), and the Marsha Forest Centre: (Canada). You can find his books and papers at inclusion.com and The Centre for Welfare reform (https://goo.gl/svgNP1)

Contact

John O’Brien

58 Willowick Dr

Lithonia, GA 30038