Positive Approaches Journal, Volume 8, Issue 4

| Site: | My ODP |

| Course: | My ODP |

| Book: | Positive Approaches Journal, Volume 8, Issue 4 |

| Printed by: | |

| Date: | Wednesday, February 11, 2026, 4:57 AM |

Positive Approaches Journal | 6

Volume 8 ► Issue 4 ► 2020

Maximizing Resources

Introduction

When one hears the phrase, “maximizing resources” one usually thinks of making dollars stretch and saving money. No doubt, getting enough revenue to meet an agency’s budget, and to meet the needs of the people they support, is vitally important. But many agencies may find that cost savings result not only in better fiscal health, but also in better services to individuals. This issue focuses on the need to employ creative ways at addressing individualized needs with scant or sometimes unavailable resources. So, to state it again, urgency in resources may present an opportunity to change … for the better. Finding more money is not necessarily the solution to some problems. Nor is it realistic, in many cases, to think that more money will make a difference. Changes in administration or programming may result not only in saving money but also in potentially helping clients live better lives. For example, individuals deciding to share housing through a supportive housing program may find the new socialization – living with other people in close quarters – to be life-changing. Save money, and combat loneliness. Agencies employing free or low-cost technology may discover more efficient ways to deliver services. Save money, and achieve more speed, agility and communication. Organizations may benefit from considering other federally funded models of coordinating care, such as the capitated coordinated care model of managed care organizations. Save money, and provide additional, efficient services such as programs to address complex needs and special needs. Tapping into existing community resources in a systematic way is another way to not only achieve better fiscal health but also to expand the universe of caring, talented people who can help vulnerable individuals. Save money and integrate clients into the community. Ultimately, the most valuable resources in organizations are the human resources. Effective leaders know how to empower their employees to creatively suggest and employ strategies such as those mentioned above. This empowerment creates a culture of continuous improvement. When leaders allow people to think differently about problems and goals, the phrase maximizing resources takes on a deeper meaning that goes beyond cost savings. Hopefully this issue will challenge readers to think outside the box and find effective ways to deliver highly personalized services in an age of high needs and limited resources.

—Dave Knauss, Human Services Program Specialist,

Office of Long-Term Living

Positive Approaches Journal | 6

Data Discoveries

The goal of Data Discoveries is to present useful data using new methods and platforms that can be customized.

Where you live matters

Pennsylvania is home to many diverse communities. From rural farmland to one of America’s largest (and poorest) cities, where you live is linked to what health resources and services you can access. In this issue of Data Discoveries, data from the Area Health Resource File (AHRF) is displayed by county to illustrate that where you live impacts access to the access to specific types of health care facilities and providers near you. The AHRF collects data from more than 50 sources to capture many different types of health care facilities and providers. The AHRF does not survey Pennsylvania data specifically and may be missing certain types of providers or facilities and pulls data from different years, which may also miss providers or facilities.

There are two components to the below data dashboard. The first component of the dashboard displays two layers of data. The first layer, estimates of the prevalence of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and the prevalence of intellectual and developmental disabilities (ID/D), are indicated by the darkness of the county shading. Research from the CDC was used to generate these prevalence estimates by multiplying them by the size of the county population. A more darkly shaded county represents a higher prevalence of ASD and ID/D. The second layer of data from the AHRF is represented on the map by the symbols with the size and color of the symbol indicating how many facilities are located in the county. The second component of the data dashboard presents the AHRF data regarding number of medical providers by county. The rate of medical providers by 100,000 people is presented on the waffle chart.

The data dashboard below starts with the map of health care facilities – to filter the map by year, population estimate, and/or facility type use the filters along the top of the map. For definitions of the facility types, hover over the ‘?’ icon in the filter. Hover over each county or facility icon to see the number of facilities and the population estimates. To get to the medical provider waffle chart, click the medical provider icon in the top right-hand corner. The waffle chart can be filtered by county and/or medical professional type. The rate per 100,000 people will appear in the top left corner of the chart, to see more detail about the ASD/ID population hover over the people icons in the chart. To return to the facility map or explore more of the AHRF data on your own, use the icon buttons in the top right-hand corner.

Pennsylvania is home to many innovative health care providers and service models. As the 5th largest state in the US, the diverse needs of the state population may require individuals to travel to reach providers or facilities needed or to consider other health care options. One way to find out about services and providers in your area is to connect to local support groups. Find the maps of support groups in Pennsylvania here: https://paautism.org/support-groups/.

Frye | 10-19

Volume 8 ► Issue 4 ► 2020

Maximizing Resources in Rural Communities for Individuals with Dual Diagnosis (Intellectual Developmental Disability/Mental Illness [IDD/MI]) For Meaningful Community Inclusions

Rachel Frye

Abstract

Community inclusion, interacting and being accepted by others is a fundamental right and basic need for establishing self-determination and respect and dignity for everyone.1 Unfortunately, there is extensive evidence of the social exclusion of people with intellectual disabilities.2 Striving to create an inclusive community that provides opportunities for integration is urgently needed for individuals with intellectual developmental disabilities and mental health concerns. This can be accomplished by maximizing the resources in your community and minimizing a reliance on paid services. This article attempts to give a perspective of the challenges and success of one organization located in rural western Pennsylvania that successfully integrated individuals with dual diagnosis (IDD/MI) into their communities. Starting with input from individuals, recognizing system gaps, working through barriers with the goal of inclusion and the experience of an “everyday life.”

___Genesis of our Community Participation Initiative

During the summer of 2019, Fayette Resources Inc. hosted trainers from the Pennsylvania Office of Developmental Programs (PA ODP) and Self Advocates United as 1 (SAU1) to train employees on “Charting the LifeCourse” methods and tools. The core belief of the “Charting the LifeCourse” framework is that, “all people have the right to live, love, work, play, and pursue their life aspirations.”3 This belief and the framework’s various tools and processes place the individual at the forefront of every conversation and stage of community engagement planning.

The Pennsylvania Office of Developmental Programs’

“Getting Connected to the Community” training also served as a resource to

Fayette Resources during the development and application of community

inclusion.4 This training brought the individual and their

interdisciplinary team together for brainstorming, community planning, and

relationship mapping. The model explains how being present at an activity can

lead to participation in the activity, which can lead to an opportunity to

connect with others involved, which can then lead to an opportunity to

contribute to the group.4 Keeping this in mind with each new

connection allows opportunity for the development of more community inclusion.4

Using

the principles provided in the “Charting the LifeCourse” training and “Getting

Connected to the Community” provided Fayette Resources with a foundation of

resources to utilize for the implementation of Community Participation Supports

(CPS) services.3,4 CPS services, “provide opportunities and

support for community inclusion, building interest in and developing skills and

potential for competitive integrated employment.”5 CPS

services should “result in active, valued participation in a broad range of integrated activities that build on the

individual’s interests, preferences, gifts, and strengths while reflecting his

or her desired outcomes related to employment, community involvement and

membership.”5

Identification of Barriers

Barriers in rural communities are similar to those experienced in large metropolitan areas; the identification of person–centered interests and identifying locations that are supportive in the community participation process so that individuals could pursue their desires, dreams, and interests.

Sometimes people are not able to identify what their interests are and who they want to engage with. This could be due to lack of life experiences or prior negative experiences in the community setting. At Fayette Resources, interdisciplinary teams who provide support services have scheduled exploratory activities or tours of their community. Exploratory activities are community activities that an individual has never experienced. By observing the individual in the new community environment engaging in a new experience, identification of a new person-centered interest may surface. Charting the LifeCourse published an “Experiences and Questions Booklet” which can be used to start and lead the conversation as to how an individual may prefer to engage in their community across their life span and through different life domains.6 The booklet enables the user to reference where they are in life (school age, transition age, adulthood, aging) and start the conversation around what life domain (employment, community living, safety, healthy living, social & spirituality, and citizenship and advocacy) they want to explore more in a community inclusive way.6

In rural communities there are a limited number of businesses, fewer recreational or social outlets, and less opportunities visually apparent. One way to move past this barrier is to utilize the relationship map offered in the “Getting Connected to the Community” training to identify what social capital already exists for the individual. In order to initiate growth in social capital for someone that may have minimal or no social capital, an interdisciplinary team could look at community connections that are already established by employees, families, or friends. These are gatekeepers.7 The Pennsylvania Department of Human Services’ “Community Participation Supports for Direct Support Professionals” training defines a gatekeeper as a “person who is already a trusted and valued member of an existing group.”7 While the individual themselves may not have an avenue into the community for a desired interest, they could use a gatekeeper as a resource to gain access to the community inclusive activity.

Once an area of interest has been identified, “The Integrated Supports Star Worksheet” offered through the “Charting the Lifecourse” framework is an excellent resource tool to use to determine a pathway for community inclusion.3 The worksheet serves as a visual brainstorming and planning tool. Fayette Resources used this tool by placing the community inclusive activity or opportunity that individual wishes to purse at the center or the “star.” The star leads the individual’s interdisciplinary team through the planning process by helping them identify the individual’s current strengths and needs, appropriate internal or external supports that are needed, community location options, and technology that is present for the identified activity.

Participation and Relationship Building

The primary goal of community inclusion is to develop meaningful relationships with others in the community that are built on common interests and are mutually supportive. Guidance and support should be provided in the establishment and sustainment of the meaningful relationship; keeping in mind that meaningful relationships are not formed overnight, but over time. As the relationship continues to grow the interdisciplinary team should modify supports allowing the individual to purse independence and personal growth.

Results

Fayette Resources began informally implementing community inclusive services two years ago. Since then the organization has incorporated the aforementioned trainings to help maximize “evidenced based strategies” in planning community inclusive activities that are person-centered.

We have witnessed individuals who receive CPS services build meaningful reciprocal relationships through community inclusion. Currently, individuals that receive services through Fayette Resources in rural communities are leading their “everyday lives” through volunteerism with 18 different groups, pursing health and wellness activities with small community groups, exploring hobbies and interests and being active members of their community.

Case Example: Maximizing Resources to Ensure Successful Community Inclusion

Daniel

is a 41-year old individual with an intellectual disability and a mental

illness (IDD/MI). Along with his dual diagnosis comes a history of trauma. He

experiences rapid changes in aggression, agitation, anxiety, depression, and

significant challenges with regulating his mood when angry. Daniel's

symptomology, related to his diagnosis, and his history of trauma have

impeded his access to community inclusion opportunities.

Daniel resided with his biological parents until the age of seven when he was removed from their care following reports of physical and sexual abuse committed by his father. Daniel resided in foster care until adulthood. He had three failed family living placements and now resides in a group home with Fayette Resources Inc. He attends Fayette Resources Inc.’s Community Participation Supports Program, where he has started working on community inclusion outcomes.

Conversations and exploratory community activities with Daniel revealed an interest in volunteerism. The team supported Daniel’s mental health needs during the community exploration process. They focused on finding the appropriate community volunteer location that would foster a positive self-image while offering Daniel opportunities to pursue meaningful relationships. A safe, trusting and supportive community environment was paramount in choosing a volunteer opportunity for Daniel.

Daniel and his interdisciplinary team reviewed his relationship map to identify Daniel's current social capital. During this review, they found that Daniel lacked social capital and natural supports. They determined the optimum pursuit of community inclusion would be through the use of a gatekeeper.

The gatekeeper member of Daniel’s team communicated information about a volunteer opportunity at a local non-profit “pay what you can” cafe. The café only served meals on Fridays and Saturdays. The gatekeeper was a childhood friend of a board member of the cafe. The gatekeeper possessed valuable knowledge about the cafe that would help the team determine if this would be a good opportunity for Daniel.

Being mindful of Daniel’s mental health concerns, Daniel and his team decided to explore this opportunity. Daniel began volunteering on Wednesdays, this was preparation day for the café, which means only volunteers would be present. This smaller volunteer group was accommodating, providing support for Daniel during periods of increased anxiety and agitation, allowing a slow transition into the community in a safe and supportive environment. Daniel shared similar positive personality traits with fellow volunteers, most notably a good sense of humor, which made the transition positive.

Daniel had opportunities to choose tasks to complete, resulting in discovering and learning new talents and improving his self-image. Daniel seemed to be very fond of a husband and wife pair who volunteered at the café. They seemed to take an interest in Daniel as well, especially the husband, Joe. An opportunity to forge a meaningful friendship was revealed.

As Daniel’s connection with Joe grew, Daniel’s emotions stabilized. He exhibited fewer outbursts in the community, a decrease in anxiety and agitation, and he was able to be himself around his new friends. Since Daniel has developed excellent coping skills his emotions have stabilized, Daniel has been able to laugh and share his sense of humor among his new friends at the café.

Daniel’s friendship with Joe is very important to him. Staff continue to support Daniel in building and maintaining this friendship with Joe. Staff have accompanied Daniel into the community to meet Joe to get ice-cream and to celebrate their birthdays together. Daniel's goal is to interact one-on-one with Joe in the community, without staff support. Daniel's support team is currently working with him to pursue this goal. The “Charting the LifeCourse Experiences and Questions Booklet” is indispensable in helping Daniel plan for one-on-one time in the community, maintaining the focus on his safety and promoting his independence.

Daniel has realized new skill sets through his volunteer experience, established meaningful relationships, and is contributing to his community. Recently, Daniel was asked to be one of the representatives of the café for a radio broadcast interview. With his new natural supports, his friends at the café, Daniel was able to successfully contribute to the interview. Having natural supports and people who understand and care about him, aided in reducing his anxiety in that new environment.

References

- Selzer M. Community Inclusion as a human right and medical necessity. The PA Journal on Positive Approaches. 2019;8(2):29-35.

- Abbott S, McConkey R. The barriers to social inclusion as perceived by people with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disabilities. 2006;10:275-287.

- University of Missouri-Kansas City Institute for Human Development,

Missouri’s University Center for Excellence in Developmental Disabilities

Education, Research and Services (UCEDD). (2012). LifeCourse Principles.

Charting the LifeCourse ™. (https://www.lifecoursetools.com/).

- Getting Connected to the Community, Practical Skills for Building Person-Centered Community Connections. (PA Department of Human Services, Office of Developmental Programs, 2018).

- Application for a 1915 (c) Home and Community Based Service Waiver. (The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, 2017). p.71.

- Charting the LifeCourse: Experiences and Questions Booklet Pennsylvania Edition. (Pennsylvania Community of Practice for Supporting Families, 2016).

- Community Participation Supports for Direct Support Professionals: Part

6 - Introduction to Community Mapping. (Pennsylvania Department of Human

Services, Published Oct. 2017).

Biography

Rachel Frye is the Director of Community Participation Supports (CPS) Services at Fayette Resources Inc. in southwestern Pennsylvania. Frye has been in this position for just over a year and has been working for Fayette Resources Inc. for more than nine years. Prior positions included Day Program Site Director, Program Specialist, and Direct Support Professional. Frye received her bachelor’s degree in Special Education and Elementary Education at California University of Pennsylvania in December of 2002.

Contact

Rachel Frye, Fayette Resources Inc.

1 Millennium Drive, Suite 2 Uniontown, PA 15401

(724) 437-6461

Priego | 20-28

Volume 8 ► Issue 4 ► 2020

The Maximization of Organizational Resources Through Continuous Improvement

Sam Priego

Abstract

The role that leaders play in maximizing the resources of their organization is described in this article. Lean, a continuous improvement mindset, scientific thinking, and organizational culture is emphasized as requirements to significantly improve the effectiveness of an organization.

When the topic of maximizing resources comes up in any type of organization it almost invariably includes conversations about belt tightening, doing more with less, or implementing cost-cutting measures. While these are important conversations to be had, the topic generally does not resonate with people; it is not appealing or exciting. There is more excitement and engagement on the job when people are empowered to change things for the better and when they understand the purpose and relevance of their work and how it makes a meaningful difference in a person’s life. It is the role of leadership in an organization to create a palpable culture of continuous improvement, where staff are empowered and have the autonomy to improve processes and solve problems without having to go through layers of rigid organizational bureaucracy. Otherwise, the notion that employees are our most valuable resource becomes an empty platitude.

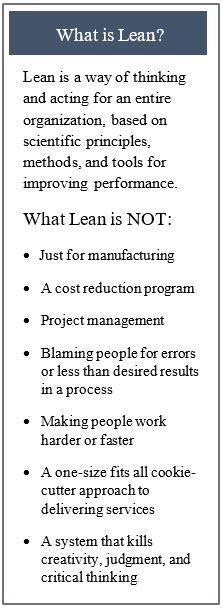

Leaders can empower others through Lean, a scientific thinking mindset that allows staff to maximize their talents, problem-solving skills, and creativity, which ultimately maximizes resources in an organization. Lean is a philosophy built on respect for people, meaning that the people who do the work know best how to improve the work. It also does not place blame on individuals when there are less than desired outcomes or results, but rather it scrutinizes the process that led to those results. Lean focuses heavily on continuous improvement through the relentless pursuit of waste elimination. Waste can be found in all work processes. It can include unnecessary wait times for the customer, mistakes or defects in a service, burdensome steps in a process, or activities that are non-value-added from the customer perspective1, see table 1.

In a 2011 study, researchers Seibert and Wang found that when employees feel empowered at work, their work performance is better, they have greater job satisfaction, and stronger commitment to the organization3. Leaders who empower have a positive effect on performance, organizational citizenship behavior, and creativity at both the individual and team levels4. For an organization to maximize its most valuable resource, its people, it must empower them beyond the conventional measures. This means developing people’s scientific thinking skills to solve problems encountered in their daily work. It is no longer only a manager’s or leader’s exclusive role to solve problems. People at all levels in the organization should be able to do this.Scientific thinking is defined as the intentional coordination of theory and evidence, whereby we encounter new information, interpret it and, if warranted, revise our understanding accordingly5. It is not the same as the scientific method, which is not always used in daily life. In his book, Toyota Kata, Mike Rother, a leading expert on scientific thinking mindset, states, “It is not about learning problem solving. It’s about learning a mindset that makes you better at problem solving.” Scientific thinking is not difficult, it’s just not our default, normal way of thinking. The “normal” way of thinking about problems is to jump to conclusions and immediately seek to solve problems because the brain does not like uncertainty. Per Rother, the unconscious part of our brain takes bits of surface information, quickly extrapolates to fill in blanks, and gives us a false sense of confidence in our conclusion.

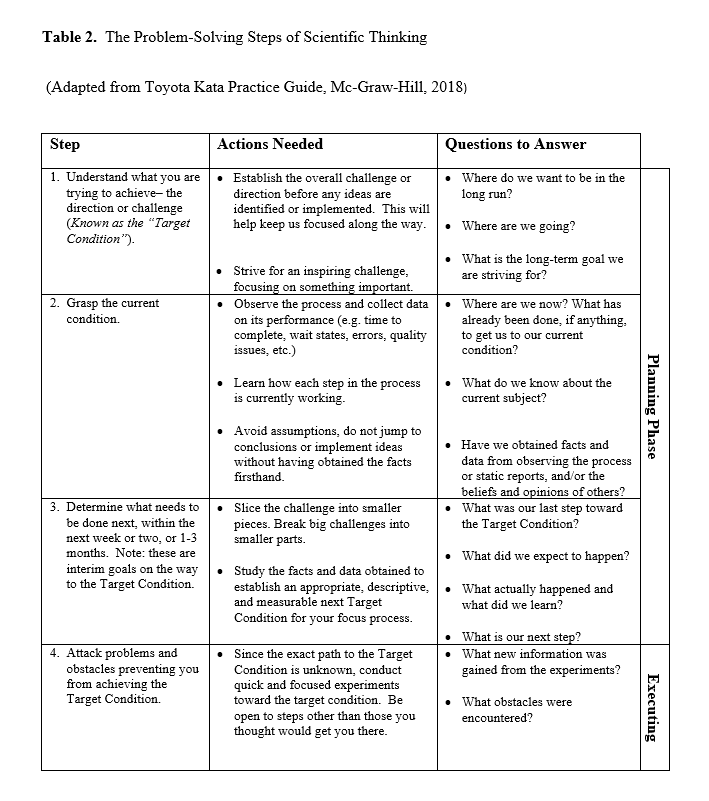

Developing new habits and allowing people to think differently about problems and goals is an ingredient to make teams and organizations more effective and successful. Just like athletes and musicians practice daily or often to develop a skill, developing a scientific thinking mindset also takes deliberate daily practice6. Below, table 2 shows the four practical problem-solving steps based on scientific thinking principles.

The application of scientific thinking in the workplace improves work processes and enables workers to identify and eliminate waste. Benefits can include costs savings, improved quality,

less waiting time, improved safety, and improved morale. For example, a small workgroup began examining the process of mailing paper notices to county assistance offices. The mailing of these notices cost between $500 to $700 in postage fees each week. The workgroup used scientific thinking to create and implement a better system. Over the course of weeks, the workgroup mapped the current process and identified waste in the process. They applied scientific thinking to create solutions that addressed the root cause of the problem, resulting in an electronic delivery of notices, and savings in excess of $36,000 a year, not including the staff time required to hand stuff the notices into envelopes and prepare them for bulk mailing.

To begin building a culture of continuous improvement will require leaders to model the behavior they want the organization to emulate7. Leaders shape people’s behavior even when they say nothing. People are watching what their leaders do (or don’t do), what they say, how they say it, how they react to different situations, and how they behave. Management consultant guru, Peter Drucker, is famously attributed for his quote, “Culture Eats Strategy for Breakfast.”8 Without the right culture in place, organizational goals, objectives, priorities, initiatives, and strategies will be constrained. The maximization of resources in any organization starts with its leadership empowering their staff by developing a scientific thinking mindset and creating a culture of continuous improvement to improve the effectiveness of their organization.

References

- Ohno T. Toyota production system: beyond large scale production. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 1988. https://www.crcpress.com/Toyota-Production-System-Beyond-Large-Scale-Production/Ohno/p/book/9780915299140.

- Krafcik J. Triumph of a lean production system. Sloan Management Review. 1998; 30(1): 41-52.

- Seibert S E, Wang G, Courtright S H. Antecedents and consequences of psychological and team empowerment in organizations: a meta-analytic review. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2011; 96(5): 981-1003.

- Lee A,

Willis S, Tian AW. Empowering leadership: a meta-analytic examination of

incremental contribution, mediation, and moderation. Journal of

Organizational Behavior. 2018; 39: 306-325. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2220.

- Rother M. Toyota Kata Practice

Guide. McGraw-Hill Education; 2017: 13-41.

- Rother M. Toyota Kata Practice Guide. McGraw-Hill Education; 2017: 46-48.

- Whitehurst J. Leaders can shape company culture through their behaviors. Harvard Business Review. Fall 2016.

- Deming E. Out of the Crisis.

Massachusetts Institute of Technology; 1982: 213-221.

Biography

Sam Priego is an experienced Lean practitioner with more than 15 years of experience spanning healthcare, city, county, and state government. Sam is an invaluable asset for organizations seeking expert guidance with process improvements, lean strategies, and leadership coaching in order to transform operations, reduce costs, and improve the client and staff experience. Sam earned a master’s degree in Public Administration from the California State University, Dominguez Hills. He currently lives in Chambersburg, PA with his wife and children.

Contact Info

625 Forster Street, Rm 602, Harrisburg, PA 17120

Phone: 717.772.4139

Email: spriego@pa.gov

[MM1]Do we want to include title, organization here?

Rizzo and Siegfried | 29-36

Volume 8 ► Issue 4 ► 2020

The Adult Community Autism Program: A Different Approach

Julie Rizzo & Kimberly Siegfried, Ph.D.

Abstract

Ten years ago, a group of individuals proposed a paradigm shift in human service delivery. Challenging the traditional model, the Adult Community Autism Program (ACAP) was developed as a comprehensive, person-centered, individualized, integrated, and cost-effective way to provide the care, supports, and services an individual needs to live a socially valued and healthy life. This article describes the advantages of this program to maximize resources through a capitated support model that provides physical, behavioral, and community-based services to adults with autism.

Ten years ago, a group of individuals created an innovative approach to supporting adults with autism. In contrast to the traditional model of service-delivery, their vision was to support adults with autism within their communities, in natural settings, rather than segregated facilities. Determined to evolve the role from that of a provider of services to that of a facilitator and community organizer, their model incorporated several key aspects: person-centered services across the lifespan; efficient, accessible, sustainable, quality, and cost-effective services; and partnership among individuals, families, government, and providers. From this vision, the model for the Adult Community Autism Program (ACAP) emerged.

In 2009, Pennsylvania Department of Human Services (DHS) obtained approval for a Prepaid Inpatient Health Plan (PIHP) under the 1915(a) authority to create the Adult Community Autism Program (ACAP) in four Pennsylvania counties.1 ACAP was the first program in the nation to use a single home- and community-based services (HCBS) provider, Keystone Autism Services (KAS), to provide an integrated system of care as a managed care organization.1 ACAP was designed to provide physical, behavioral, and community-based services to adults with autism not limited to Medical Assistance service definitions. KAS, a subsidiary of Keystone Human Services, functions as a service provider as well as the managed care organization. All health services as well as behavioral, skill building, and community supports are coordinated and provided by ACAP. This model was designed to maximize continuity, flexibility, integration, and coordination of a wide range of services for participants, and thus maximizing resources. ACAP is guided by the following foundational principles:

- Every

person living with an Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) can experience a

meaningful and quality life

- Every

person with ASD can grow and learn for the entirety of their life

- Services

are comprehensive, highly individualized, flexible, and continuously adapted to

the person’s needs and preferences

- Services

are community based and make maximum use of the capacity of the family,

friends, neighbors, and community at large

- Therapeutic

strategies are evidence based and are carried out by a highly qualified

clinical team

- The

effectiveness of the program is continuously measured

- The

program makes maximum use of innovation, creativity, and technology to support

successful functioning

ACAP operates as a fully functioning Managed Care Organization (MCO) where KAS receives a capitation payment and takes risk for 200 individuals. ACAP Participants must disenroll from their HealthChoices Plan and enroll in the ACAP as their insurer. ACAP is responsible for clinical and administrative oversight of all services provided pursuant to an individual support/care plan. ACAP contracts with a provider network of physicians, as well as psychologists, therapists, counselors, and nutritionists. An administrative third-party organization (TPO) is responsible for processing billing and claims. ACAP manages and pays all health services, with exception of hospital, diagnostic, laboratory, and pharmacy services, which are covered by private insurance, Medicare or Medical Assistance.

ACAP has incorporated many strengths of the traditional MCO approach such as the capitation payment methodology matched with the responsibility for coordination of all care and services. ACAP has been able to bridge the traditional health services to the traditional waiver services and successfully coordinate and integrate the services. ACAP is not just a model for the young, healthy, and singly diagnosed adult with autism. The majority of individuals in ACAP have co-existing medical and/or mental health conditions. Supports for individuals served reflect careful consideration of the impact of comorbidities. As an MCO, ACAP has a responsibility to manage the health and wellness of its participants. Hiring clinically skilled staff has helped ACAP succeed in making progress with individuals. ACAP serves individuals with a broad range of support and supervision needs. Currently there are seven individuals living in a licensed residential setting with five of those individuals having significant medical needs. There are four individuals for which ACAP provides 24/7 support with limited natural supports, and there are nine individuals which are dependent on support shared by family and ACAP. The capitated model works with a mix of those independent individuals with those needing a higher level of care and support.

ACAP is able to maximize resources by having an adaptive, flexible, integrative team approach. With in-house supports coordination and a team led by a behavioral specialist, an individual’s supports and services can be changed quickly to meet the needs of the individual and/or family. ACAP also has the ability to identify non-traditional services that are deemed medically necessary to meet the needs of each individual. This provides flexibility to address important issues. For instance, gym memberships have been purchased for participants to address underlying medical issues including obesity, to provide a typical role for the individual, and to afford community inclusion and socialization in a typical setting. The internal supports coordination process permits efficient flexibility in service and supports authorization and delivery.

ACAP is structured to focus on outcome measures in addition to process measurements. The program is highly person-centered, clinically driven and integrated. The outcomes measured include improving the stability of participants, increasing community participation, independence, and meaningful engagement (employment, volunteering, and higher education), and improving access to medical services. With an individual’s team led by a behavioral specialist, services are driven by data-informed decisions based on progress the participant is making on their own person-centered goals, on an analysis of the annual assessments, on a review of medical needs, and on what the participant finds most important in their life.

Employment was an early goal identified for ACAP. The chance to serve in a valued role and earn money is very important for individuals. ACAP’s model allows for the focus towards integrated and competitive employment through skill building related to job searching, resume writing, interview skills, applying for jobs, volunteering, and/or higher education. Current data indicate this to be a highly successful service, with over 55% of ACAP individuals being competitively employed. Data are also gathered and assessed for the following quality indicators: volunteer work, number of hours participants work or are engaged in volunteer work, type of employment, and involvement in higher education.

Finally, the inclusion of health

services, along with behavioral health and other support services in a truly

integrated approach is an important part of the success of ACAP. Individuals

and their families are spared the challenge of navigating multiple systems to

meet their various medical and behavioral needs. ACAP successfully developed a

network of healthcare providers so individuals can obtain access to the care

they need. For these reasons, ACAP participants are largely successful with

completing annual physical, dental, and gynecological exams. As ACAP evolves,

so too does its impact on health with a focus on exercise, nutrition, and

medication.

In conclusion, the

ACAP structure and approach allows KAS to maximize resources for a truly

comprehensive, person-centered, individualized, integrated, and cost-effective

way to provide the care, supports, and services an individual needs to live a

socially valued and healthy life.

References

- Pennsylvania Department of Human Services Medical Assistance Quality Strategy for Pennsylvania. Health Choices website http://www.healthchoices.pa.gov. Published April 20, 2017. Accessed January 29, 2020.

- IHI Triple Aim Initiative: Better Care for Individuals, Better Health for Populations, and Lower Per Capita Costs. Institute for Healthcare Improvement website www.ihi.org/Engage/Initiatives/TripleAim/Pages/default.aspx Accessed December 27, 2019.

- The Center for Consumer Information & Insurance Oversight: Medical Loss Ratio. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services website www.cms.gov Published July 24, 2018. Accessed December 27, 2019.

Biographies

Julie Rizzo is the Executive Director for Keystone Autism Services and provides program administration for the Adult Community Autism Program as both the managed care organization and provider services.

Kimberly Siegfried, Ph.D. is the Clinical Director for Keystone Autism Services and provides clinical oversight as well as training and consultation with treatment teams to ensure efficacy of supports and services provided to participants. Dr. Siegfried collaborates with Julie Rizzo to align clinical and operational resources to optimize program outcomes.

Contact

Julie Rizzo, Executive Director

Keystone Autism Services

3700 Vartan Way

Harrisburg, PA 17110

(717) 220-1465

Todd | 37-45

Volume 8 ► Issue 4 ► 2020

Innovative Approaches to Gather Community-Based Service Data

Deborah Todd

Abstract

Data collection is an essential expectation of service grounded in Applied Behavioral Analysis (ABA). The Behavior Analyst Certification Board (BACB), 4th Edition Task List H-01, indicates, “select a measurement system to obtain representative data given the dimensions of the behavior and the logistics of observing and recording.”1 The need to collect data in community-based settings to report progress on goals can create some challenges including how to collect data while providing treatment in a setting where safety must also be ensured and having some mechanism to communicate the data collected efficiently. This article will describe one provider’s approach to collecting data in the community while addressing the aforementioned and other challenges.

Focus Behavioral Health is a community-based provider, providing supports to adults with Autism and or an Intellectual Disability in the state of Pennsylvania. One of our organizational objectives is to use data efficiently and effectively to help individuals to reach their fullest potential. Initial concerns related to meeting this objective involved the lag in time that data were collected and shared to ensure data integrity and accuracy. Existing data-based platforms did not meet our needs nor were they specifically aligned with the regulations of the programs we are enrolled in; therefore, we developed our own platform, Reliable, to meet all of the data collection and progress reporting requirements of the waiver programs and to address potential barriers we identified in our evaluation of other platforms. Key features of our program include the use of iPads, pre-populated objectives for easy tracking, safeguards embedded within the program to help prevent fraud and errors, easy submission of notes through electronic synchronization of the clinical documents, and a two-step passcode protection process to ensure HIPPA compliance.

Staff training is critical to the success of this model. Staff are trained to the chosen objective. They are taught how to break the objectives down so that they know what replacement behavior or targeted skill they are collecting data on. Additionally, the training focuses on forms of data measurement systems and creating opportunities to address the objective. The interventions outlined in the participant’s plans are described for the staff so that they understand how to implement the intervention and record the participant’s response to the intervention. During the training, staff are presented with sample scenarios and are tested on the ability to create a documentation note based on a scenario so that the trainer can assess basic understanding of their data collection skills. Staff also shadow a Behavior Support Specialist, Skill Building Specialist, or a Program Supervisor to ensure that they understand how to create opportunities to work on the objectives, how to implement the interventions within the community setting, how to complete the data collection tool correctly, and how to translate this into the clinical documentation captured in Reliable.

Ongoing supervision and support are also included in this model. It is expected that the Behavior Support Specialist or the Skill Building Specialist provide consultation with all staff responsible for collecting data at a minimum of twice per month. They provide consultation regarding how the objectives the participant selected to work on are being addressed within the natural environment, they observe the staff implementing the objectives outlined in the participant’s plan, they provide training if an intervention is not being utilized as designed, and they may take their own data as a sample of interrater reliability, and address any discrepancies in data collection. The Behavior Specialist or Skill Building Specialist are integral to ensuring that all staff working with the participant are identifying the targeted behaviors and replacement behaviors/skills and are collecting data in a consistent manner.

There were initial concerns about how the participant would respond to this data tracking system. To alleviate these concerns, the participants are introduced to the iPad system at their initial intake meeting to review expectations and answer any questions. The participant is involved in the development of their goals and objectives, and once they are established, they are reviewed on the iPad with the participant so that they are aware of what appears on the forms. As the parameters about the data collection system have been reviewed from the beginning, staff remain open with participants about the need to collect data during sessions. Since the bulk of the clinical documentation and data are collected within the session, staff review the data and any other observations, concerns, and next steps with the participant before leaving for the day. As the objectives are reviewed within each session, the participant becomes familiar with their objectives, making it easier to maintain treatment integrity in the community setting.

Barriers and Solutions

A project workgroup began by identifying common barriers to community-based data collection systems, and a review of the requirements of the waiver programs.

The first barrier identified was treatment planning with unclear or vague definition of behavior(s) or targeted skill(s). If staff were not clear on what data to measure, data could not be reliably gathered. For example, a vaguely written objective such as “will increase social skills” is not clear, not defined and subjective to the staff’s interpretation of the behavior. To avoid this problem, supervisory staff, with supporting information from the Functional Behavioral Assessment (FBA) Processes and Behavior Support Plan (BSP) and input from the participant and his/her family, are responsible for developing the objectives and uploading them into Reliable.

The second barrier identified was the need to collect data in the community setting while balancing the need to focus on the participant. To ensure easy access, all staff are provided with an iPad. The iPad has two layers of security within it to keep participant’s information private, requiring passcodes at both the home screen and the entry point to Reliable. The forms are structured within our Reliable server and are released only to the participant’s direct staff by an administrator. Reliable lists each participant they are supporting and the clinical document form that contains pre-populated goals and objectives. When supporting a participant, the staff are encouraged to review the objectives with the participant identifying priorities for the day and how the participant would like to address the objectives (for example, cleaning can mean many different things- cleaning their kitchen, the bedroom, the car); this way the staff are already thinking as to how to create opportunities to work on the objectives. Since iPads are a common piece of technology in community settings, staff are taught to casually use their iPad to capture data so that the data is reliable as it is being recorded in close proximal time within the time spent with the participant. If not done this way, staff may not remember the exact number of opportunities that were presented to work on the skill or replacement behavior and the number of successes, as well as the number of prompting that was needed.

The third barrier we identified was the need for data to be easily accessible for analysis. Too often in paper pen systems there is a delay with staff sharing their notes and we had experienced many staff who did not meet timelines. The delay impacts the ability to review the data as they have to physically come to an office during hours when they are commonly actively working with participants. With our Reliable system, staff are encouraged to complete the note that evening and sync it to the server. At minimum, it is mandatory they sync the iPad on Wednesdays and Sundays of each week. Therefore, the maximum number of days that would lag between a session and the submission of the clinical documentation is three days. Once it is synced, administrative staff have immediate access to the data. This allows data to be summarized in a timely manner to provide data based instructional decisions on next steps in supports for the participant. It also allows for immediate follow up with the staff if they do not submit their notes by the established deadline, as administrative staff can easily view who has and who has not submitted clinical documents on time. This timely submission can quickly identify simple errors, such as a note missing a section by labeling them as “incomplete” and puts the color of the note in red. Identifying these errors in data collection errors early allows for quick correction and staff training, if necessary.

Results

Initially Focus’s administrative team had much discussion regarding the cost of developing the program and providing iPads for staff. While there was a significant upfront cost, the administrative team was able to see immediate outcomes within the first year of implementation. First, administrators were able to track utilization on a weekly basis and follow up with direct staff if a participant’s hours were not utilized according to their Individual Support Plan. Second, because notes are submitted consistently twice a week, the billing is kept up to date and submitted within a timely manner, preventing lags in reimbursement. Specifically, the claims submitted for payment under the Reliable system are submitted 80% quicker than in the past. Third, the paybacks Focus had at audit due to billing errors were reduced by 90% and we have increased revenue due to the reduction in amount of claims that we could not submit for billing, either because we did not receive the clinical documentation in a timely manner, it was submitted incompletely, or there was an over utilization of units.

A primary reason we wanted to our data collection to be technology based was because of the potential impact for participants. For example, one participant had an objective regarding reducing socially inappropriate behaviors (i.e., purposefully belching, passing gas, touching other’s food), as well as reducing self-harm behaviors (i.e., threats to cut self, expression of suicidal ideations). We found, through easy data analysis of this data collection system, a correlation between socially inappropriate behaviors and an increase in self-harm behaviors. We were able to use this information to help the treatment team look closer at socially inappropriate behaviors as an indicator of impulse control issues, and start to put additional strategies in place to reduce the risk of self-harm, having the potential to make a huge impact in the everyday life of this individual.

Reliable lends itself to a higher level of consistency in communication with staff. For example, if a staff member calls off, a supervisor can see from the clinical documentation of the session last provided and communicate the information to the substitute staff. Efficiencies in managing staff and streamlined services and supports while acknowledging staff turnover and need for substitute staff are also positive outcomes related to the adoption of this system.

Discussion

As Focus is preparing to expand this model to the services we provide in other waivers, several things were considered. First, given the number of employees we have, the anticipated growth rate needs to be factored in the budget based on the number of iPads to be purchased. Second, programmers were consulted regarding the cost of modifications to the Reliable program for the purpose of meeting the expectations of other waivers. Third, a pilot of the Reliable program is important to provide staff an opportunity to try the system and provide feedback to make this a system that is relevant to their programs.

Overall, the use of technology has improved our

operations and the services and supports we provide to participants. Not only

are staff and participants more cognizant of the objectives contained within

the support plans but data has been recorded more accurately, in general. This

system has also improved the ability to control for timelines in which clinical

documents are received and can be reviewed by a supervisor and it has prevented

common errors in billing, reducing payback at audit from occurring. Reliable has assisted in making staff

training more efficient and streamlined through enabling a more efficient

analysis of data that is used to support programmatic changes for participants

and our programs. A model such as Reliable

can be easily adapted for other service provider’s needs and operations.

References

- BCBA/BCaBA Task List Fourth Edition. BACB.com. https://www.bacb.com/bcba-bcaba-task-list/.

Biography

Deborah Todd is the Clinical Coordinator of Focus Behavioral Health, Inc, which is an agency that provides supports to adults with Autism through the Pennsylvania Adult Autism Waiver. She has been in this position for 5 years. Prior to this position, she was the Director of a Children’s Behavioral Health Rehabilitation Services (BHRS)/Wrap Around agency, providing home and community-based services to children on the Autism Spectrum, for 15 years. She holds a Master’s degree in Special Education from the University of Pittsburgh and is a Board-Certified Behavior Analyst.

Contact Information

Deborah Todd

Focus Behavioral Health

4261 William Penn Highway

Murrysville PA 15668