Positive Approaches Journal, Volume 9, Issue 1

| Site: | My ODP |

| Course: | My ODP |

| Book: | Positive Approaches Journal, Volume 9, Issue 1 |

| Printed by: | |

| Date: | Friday, February 27, 2026, 4:17 PM |

Positive Approaches Journal | 6

Volume 9 ► Issue 1 ► 2020

Navigating

the Justice System: Considerations, Best Practices, and Points to Ponder

Introduction

I have worn many hats during my legal career over the past 43 years: as a federal prosecutor, a state prosecutor, a criminal defense attorney, a Parole Board Member, and a State Court Judge. However, I also acquired invaluable, non-legal insights as the father of a 30-year-old man who lives independently with the challenging cocktail of autism, anxiety and ADHD. While the books about autism that I collected over the years are informative, I found that the skills learned as a parent and engagements with other supporters were more helpful for my responses to those autistic individuals whom I encountered in the legal system.

The Criminal, Civil, Family and Orphans Divisions of the courts in Pennsylvania provide the judicial framework for the resolution of disputes. Involvement in the adversarial system is stressful and challenging for neuro-typical adults and children but is even more so for neuro-diverse individuals. Although researchers have come a long way since the work of Dr. Leo Kanner and Dr. Hans Asperger in the 1940’s, the various divisions of the justice system still have much work to do when dealing with participants who may be struggling with disabilities. It remains essential that all stakeholders in the legal system continue to provide thoughtful training -- and effective communication -- to all participants in order to ensure continued improvement of the way people with disabilities are treated within those systems.

—William F. Ward is a partner in the law firm of Rothman Gordon, P.C., of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

Positive Approaches Journal | 7-13

Data Discoveries

The goal of Data Discoveries is to present useful data using new methods and platforms that can be customized. For optimal viewing and engagement, use the full screen function at the bottom of this section.

Data Hunting: Finding the right source for your research question.

Finding the right data to answer questions, whether in your personal or professional life, has become an invaluable skill in recent years. With so many data sources out there, how can you tell what sources are reliable and what sources should not be trusted? In this issue of Data Discoveries we present you with a guide to finding the right data source for your research question. In the dashboard below, click on the rectangles or arrows along the top of the dashboard to move through the sections of the guide.

Dubin | 14-26

Volume 9 ► Issue 1 ► 2020

Autism, Sexual Development & the Criminal Justice System

Lawrence A Dubin

Last year I was giving a speech before a few hundred people and I posed this question: Has anyone ever had the experience of waking up when everything seemed to be in order and then something unexpected happened that same day that was life changing? Many people raised their hands expressing the sentiment that life is highly unpredictable and that we all live in a vulnerable state.

On October 7, 2010, my life changed radically. I was driving to the law school where I teach. It was a beautiful fall day. I had just left a restaurant after having a hearty breakfast, feeling that life was as good as it gets. Seemingly, out of nowhere I received a call on my cell phone from an FBI agent informing me that my autistic son' s apartment had been the subject of a search warrant based on the belief that there were illegal images on his computer. The agent advised me to go to his apartment immediately as he was in a terrible emotional state. As I made a U-turn to see my son, I knew that from that day forward, my life would never be the same.

As both a lawyer and a law professor specializing in the area of legal ethics, I have had a lot of faith in the importance of teaching law students about the role lawyers play in searching for justice especially in criminal cases. I believed in our legal system. I knew this system was not perfect, but I also believed it to be the best in the world. My faith in that system was shattered when my son was arrested for a non-contact sexually related federal offense that was committed in the privacy of his apartment - possession of child pornography. What I came to later understand as a result of this harrowing experience is that many people with autism are vulnerable to falling into the criminal justice system without any understanding of why their conduct was criminal. In other words, a criminal act may have technically been committed, but without any intent, in part, due to the characteristics of being on the autism spectrum. Instead of using my son's case to explain how the legal system can misunderstand and mistreat people on the autism spectrum, I am going to use a case study of another case of an autistic man who was charged with a similar offense. I have already written extensively about my own experience: Caught in the Web of the Criminal Justice System: Autism, Developmental Disabilities, and Sex Offenses co-written with Emily Horowitz, Ph.D1. The sources for the information provided in this article are supported within the contents of this book.

My objective in writing this article is first, to inform parents and other people who may or may not be professionals who provide important support for people on the autism spectrum and second, to expand the knowledge and understanding of defense lawyers, prosecutors, and judges who operate the criminal justice system and allow them to view the increasing number of men being diagnosed on the autism spectrum who are or have been charged with certain types of sex crimes more compassionately. These people need to receive appropriate mental health services in order to understand the social prohibitions of what they have done. These services may simply be to provide adequate sex education specifically designed for people on the autism spectrum.

When those who operate the criminal justice system misread this population as posing a serious danger to children and others, tragic consequences can burden the lives of individuals with autism including a criminal record, incarceration, and becoming a registered sex offender.

The diagnostic criteria for an autism spectrum disorder focuses on persistent deficits in social communication and social interaction. What is not specifically mentioned is how these major deficits can impede normal sexual development from the moment of birth into adulthood. Those on the autism spectrum have great difficulty making friends or having the verbal skills to socialize with others. Yet the subject of viewing people on the autism spectrum as sexual people who, due to their disability, have roadblocks to learning and experiencing normal sexual development is ignored.

Sex is a difficult subject for parents to discuss with their children, but much more so for parents with children on the spectrum. Yet, these defined deficits for people on the autism spectrum help to explain how such difficulties surrounding healthy sexual development are not their fault. This omission of deficits in normal sexual development as a diagnostic characteristic of autism has furthered the lack of understanding of autistic defendants within the criminal justice system. Just as a blind person should not be treated the same as a person with normal sight in a criminal trespassing case, an autistic person who has been diagnosed as having the characteristics of mind blindness, or theory of mind, (i.e., lacking a natural ability to form an awareness of other people's thoughts) should not be treated the same as a neurotypical person in evaluating certain types of criminal sexual offenses.

What also adds additional difficulty in assessing someone on the autism spectrum in a criminal case, is that they often have normal or even above-normal intelligence. However, they also have a large gap between intelligence and social development which is not clearly visible. Social research establishes that those with ASD typically possess social skills far below their age group yet are normal in their biological sexual development2.

Their hormones are age appropriate, but their lack of social skills make having direct and normal sexual experience nearly impossible. In addition, their intellectual development may cause them to appear extremely skilled in computers or highly competent in mathematics as well as in many other areas of their interest.

Some background information is offered to better understand the case study mentioned hereafter. The crime of possessing child pornography is a rabbit hole for many people on the autism spectrum to violate without any intent to do so. This crime is usually committed through a computer which is a common way for autistic people to learn about the world without having to engage in socializing with others. This criminal act is done in the privacy of one's dwelling.

With most crimes, prosecutors are required to prove that the accused not only committed the criminal act, but also had the intent/requisite state of mind to violate the law. The federal law criminalizing unlawful images on a computer in the case study presented does not require any proof of state of mind, only the presence of the illegal images on one's computer. The mind blindness of people with autism masks the illegality of this crime and leads the users to the reasonable assumption that these images aren't illegal otherwise they wouldn't be on the computer. Furthermore, there is no disclaimer informing potential users that viewing these images is a federal criminal act.

In an unbiased study of adolescents in Pennsylvania charged with various sex crimes, it was found, after a thorough clinical evaluation, that 60% of these teens were diagnosed on the autism spectrum. Is there any possible explanation why such a large percentage of those on the autism spectrum might be swept into the criminal justice system3?

Dr. Ami Klin, Head of the Autism Department, Emory University, has stated that people on the higher end of the autism spectrum have, "a disability of social cognition, social learning and communication [...] Adults, even those with high measured intelligence, may, in a practical sense, function like much younger children both emotionally and in their adaptive (life skills) behavior. Expectations for their understanding, skills and abilities are misplaced if development is based on IQ and chronological age4."

Gary Mesibov, Ph.D., a respected international expert in autism has stated, "people with ASD often get into trouble without even realizing they have committed an offense. Offenses such as [...] child pornography and stalking [...] would certainly strike most of society as offenses that demand some sort of punishment. This assumption [...] may not take into account the particular issues that challenge an ASD individual5."

John Elder Robison, a best-selling author who is on the autism spectrum, states that autistic defendants who are charged in sex crime cases, "needed much more help than punishment. Ignoring that reality is like ignoring the teachers who locked autistic people in basements at school when I was a kid5" Experts in autism view the actions of those on the spectrum differently than criminal prosecutors. These experts understand the behavioral impact of ASD on the person's undeveloped sexuality whereas a prosecutor may see that same history as being irrelevant to the crime committed.

Case Study

An adult man in his 30's, who I will refer to as Jeff (not his real name), was charged with the federal crime of possession of child pornography punishable up to ten years in federal prison. Both of his parents are highly trained professionals. Jeff's defense lawyer had represented over sixty men facing similar charges and was aware of their vulnerability and lack of understanding as to the criminal nature of their acts. Jeff was diagnosed with Asperger's when he was 11 years old. As a young child he displayed a lack of social interest in other children and had significant neural developmental impairments. While at times displaying unusual behavior, testing showed he had a gift for understanding mathematics and computers while his nonverbal reasoning, reflecting his social skills, scored a 20-point gap from his verbal reasoning. In other words, his social skills substantially lagged behind his intelligence.

During his adolescence and into adulthood, Jeff's severe social delays and other neurological symptomology led his parents to assume that he showed either no sexual interest or that it was severely delayed. Sex did not seem to be on his mind and his parents felt inadequate to discuss sex with Jeff in a meaningful way. The many therapists who had worked with Jeff also seemed to lack the competence to broach the subject of sex with him. In fact, Jeff had not experienced any type of sexual experiences with other people. Nevertheless, his parents felt optimistic about Jeff's development because his knowledge of computers could lead to future employment opportunities.

On the day that their lives suddenly changed forever, Jeff’s parents remember attending a church service and giving thanks for the progress their son was making. Soon after coming home, there was a knock at the door. Jeff's father opened the door to men dressed in camouflage, wearing helmets and bullet proof vests who barged into his home. The entire family, father, mother, son, and teenage daughter were ordered to drop to their knees and put their hands behind their backs. They grabbed Jeff from his bed and brought him to the living room. They then searched the home. After doing so, they took Jeff back to his room and told him he had child pornography on his computer and obtained a confession from him. Jeff was taken to a police station and later released to his parents the same day without any restrictions being imposed on him.

The family' s entire criminal history consisted of one traffic ticket. Over the next three years, nothing further happened in relation to this event. Thereafter, Jeff was suddenly and unexpectedly notified that he was being arrested for the federal crime of possession of child pornography. Jeff’s parents were shocked that their socially reclusive and neurologically quirky son who had shown no interest in sex would be arrested for a serious federal crime. They were also shocked to learn that such sexually illicit material not only existed on the internet, but that it was easily accessible, free of charge, and without any explicit warnings being given that that possession of these images was a federal felony.

The government clearly didn't see Jeff as a danger to society as no restrictions had been placed on his life during the interim period before charges were brought against him. His parents hoped that the federal prosecutors would understand how a person with autism who lacks the social skills engaged in sexual development could use a computer to view images as a way to learn about his sexuality in the privacy of his home. Experts in autism understand that viewing these images of minors does not indicate a desire to engage in sexual activity with them because that would require a higher level of social skills7

Once charged with this crime, Jeff lost his job, was required to wear an ankle bracelet, lost his freedom by being placed in home confinement, and had to report to a pretrial officer on a regular basis. Two more years passed during which time Jeff’s parents paid thousands of dollars in legal fees for legal representation, and expert witness evaluations and report s. Jeff agreed to plead to a reduced charge of transporting obscene materials. Since this criminal conviction would not be for child pornography, there was the reasonable assumption that incarceration and registration as a sex offender would not be punishments for Jeff.

Unfortunately, that assumption was proven wrong. Even though the prosecutors in Jeff's case did not ask incarceration, the federal judge who presided in his case sentenced him to three years in a federal prison that was six-hundred miles from his home. Upon Jeff' s release from prison, he was ordered to register as a sex offender.

How could our legal system allow such a miscarriage of justice to occur? The answer is this: experts in autism have a completely different understanding of individuals with ASD than prosecutors do. Whereas autism experts understand that most men with developmental disabilities, like Jeff, are not dangerous and that they may unwittingly commit criminal acts without any intent to violate the law, prosecutors mistakenly view anyone who possesses these illegal images as being extremely dangerous and likely to hurt children. The data on this issue supports the position of the autism experts.

The good intentions of laws that are enacted to protect vulnerable children cannot be rationalized if the cost is the dehumanization of another vulnerable population - those with developmental disabilities who pose no danger to others. Jeff represents a class of people who are being victimized by the government without any benefit to the public. Jeff' s father said that when he was dropping his son off at the prison where Jeff was to serve his three year sentence, he looked his son in the eyes, told him he loved him, and then drove a few miles away and cried like he had never cried before.

As is true for most parents with a child on the autism spectrum, Jeff's mom and dad were always there to protect their vulnerable son from others, including insensitive teachers, unhelpful therapists, and the bullies who taunted Jeff at school or at work. Leaving his son to be a prisoner at a federal penitentiary six-hundred miles away meant that he could no longer protect Jeff as he had always done. Knowledge of that fact permanently broke his heart.Advice

To Parents:

1. Understand your child is a sexual person even if he or she shows no interest in sex.

2. Monitor the use of your child's computer.

3. Get the best professional support that you can for your child.

4. Make sure your child understands that if ever questioned by police, to inform the officer that they are on the autism spectrum and that they should not make any statements unless their parent or a lawyer are present. Otherwise, the police will likely take advantage of your child in acquiring an incriminating statement.

To Therapists:

1. Only work with people on the autism spectrum if you possess expertise in autism and understand the social and sexual issues that they must confront.

2. Be aware of the dangers and pitfalls your client could face if encountering the legal system.

To Others Who Serve This Population (e.g., group home staff, behavioral specialists, etc.):

1. Report any observed sexually inappropriate behavior to professionals who are available to properly provide the necessary assistance.

2. Inform parents about any sexual norms that are misunderstood by their child if they can seek further helpful professional interventions.

To Prosecutors:

1. Remember that your legal and ethical goal is TO SEEK JUSTICE. That means that a criminal conviction is not always the best objective to achieve in the case of a person with a developmental disability.

2. When dealing with a defendant on the autism spectrum, determine whether the charged offense is related to his/her developmental disability and whether the person is a danger to society. Use reasonable discretion to divert the person from the criminal justice system. Instead provide conditions that will ensure appropriate sex education and other mental health support to prevent any further criminal acts from occurring.

To Defense Lawyers:

1. Do not represent a person on the autism spectrum without a complete knowledge of whether the crime charged is related to the characteristics of their developmental disability.

2. Your important task is to gather highly qualified experts who can help prosecutors understand that your client is not dangerous and needs mental health support rather than a criminal conviction.

3. Fight to keep your client from being incarcerated or becoming a registered sex offender.

References

- Dubin, Lawrence, and Emily

Horowitz. Caught in the Web of the Criminal Justice System: Autism,

Developmental Disabilities and Sex Offenses. J. Kingsley, 2017.

- Gougeon, NA. Sexuality and autism: A critical review of selected literature using a social-relational model of disability. American Journal of Sexuality Education. 2010;5(4):328–361. doi:10.1080/15546128.2010.527237.

- Sexuality and autism: a critical review

of small selected

literature using a social-relational model of disability. American

Journal of Sexuality

Education 5(4):328-361.

- Sutton L, Hughes T, Huang A, et al. Identifying individuals with autism in a state facility for adolescents adjudicated as sexual offenders: a pilot study, Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities. 2012; 28(3):1-9.

- Attwood T, Henault I, Dubin N. The Autism Spectrum, Sexuality and the Law - What Every Parent and Professional Needs to Know. Jessica Kingsley Publishers; 2014:168.

- Attwood T, Henault I, Dubin N. The Autism Spectrum, Sexuality and the Law - What Every Parent and Professional Needs to Know. Jessica Kingsley Publishers; 2014:169.

- Attwood T, Henault I, Dubin N. The Autism Spectrum, Sexuality and the Law - What Every Parent and Professional Needs to Know. Jessica Kingsley Publishers; 2014:167.

Biography

A professor of law at the law school since 1975, Lawrence A. Dubin teaches courses in legal ethics and litigation. He was appointed by the Michigan Supreme Court to be a member of the Michigan Attorney Grievance Commission from 1978 to 1986, serving at times as its chair. Prof. Dubin served for many years on the State Bar of Michigan's Standing Committee on Grievance and is currently the co-chair for the State Bar's Lawyers and Judges Assistance Committee. He has authored books on the subject of legal ethics, evidence, and trial practice and has written many articles on the subject of legal ethics. An invited guest on radio and television programs, Prof. Dubin is also a frequent media commentator on legal matters and is often quoted in the local and national press. The State Bar of Michigan has twice awarded him the Wade H. McCree, Jr., Award for the Advancement of Justice for his public television programs, and in 2018 it awarded him the John W. Reed Michigan Lawyer Legacy Award. He was also written extensively on the subject of autism and the criminal justice system.

Contact Information:

Lawrence A. Dubin

Gosselin & Sands | 27-54

Volume 9 ► Issue 1 ► 2020

Collaboration to Continuity: A Case Study Narrative on Berks County’s Mental Health

Forensic Diversion Program

Brandon Sands and Jillian Gosselin

Abstract

The number of individuals with mental illness diagnoses incarcerated each year continues to grow. Individuals with mental illness diagnoses often stay in jail longer, are less likely to post bail than those arrested for similar offenses and are more likely to experience significant delays in case processing than those who do not have a mental illness diagnosis1. “Research has identified that the criminal justice system may contain bias toward individuals with mental health diagnoses and has documented instances of improper treatment of individuals with mental health diagnoses while incarcerated2.” While many jails and prisons continue to be ill-equipped to provide adequate mental health care; these facilities are often where individuals first receive treatment and are identified as having a mental health condition2. Incarceration often exacerbates already present mental health symptoms and lends itself to the development of additional mental health concerns.

Introduction

Prevalence of mental illness diagnoses among local jail inmates are very high. One in six inmates who had a mental illness received treatment since detainment. Just over a quarter (26%) of jail inmates who had a diagnosed mental illness, compared to a fifth of those without, had served 3 or more prior incarcerations2. While incarcerated, 19% of jail inmates with mental illness were charged with violating facility rules compared of to only 9% of the overall inmate population. Those with a mental illness were three times as likely to be injured in a physical altercation since admission (9% compared to 3%).

The majority of offenses being committed by those with mental illness are minor such as trespassing, public intoxication, and other nuisance offenses3. These individuals are often arrested multiple times for similar offences over short periods of time and their risk for arrest is often increased due to substance use, homelessness, and unemployment.

Mental Health (MH) disorders are highly correlated with substance abuse (SA). About 76% of local jail inmates who had a mental health diagnosis also met criteria for substance dependence or abuse2. There are an estimated 4.2 million adults living with a Co-Occurring Disorder (CODs), which is a diagnosis of mental illness along with a substance abuse diagnosis4. Many times, CODs can influence and aggravate each other when left untreated2. Although improving considerably, only 12% of offenders with CODs received services for both disorders in 20122. Over 76% of State inmates with a MH disorder have a co-occurring SA disorder. Inmates with CODs have much higher rates of homelessness (133% higher), past physical or sexual abuse (58% higher) and parents who also were abused (71% higher)2.

Due to offenders facing multiple barriers to rehabilitation and crime-free lives and those with mental illness diagnoses being at a substantial disadvantage, forensic diversion and The Stepping Up Initiative were developed. Forensic diversion aims to assist an individual with mental illness to avoid or reduce jail time by linking them to community services. In many cases, where their charges are minor and the sanctions are limited, individual can be linked to community-based services without any reduction in jail time5. In diversion programs, early screening and engagement is key to minimizing contact with the justice system and even avoiding a short jail stay. The Stepping Up Initiative acknowledges that those with mental illness are overrepresented in the jails and are taking a toll on the criminal justice system.

Stepping up Initiative

The Stepping Up Initiative was launched in 2015 by the National Association of Counties, the Council of State Governments Justice Center, and the American Psychiatric Association Foundation to mobilize local, state, and national leaders to achieve a measurable reduction in the number of individuals in jail who have mental illness as the number of those incarcerated with mental health illness diagnoses has far surpassed those receiving treatment in hospitals. Berks County was chosen as one of eleven Innovator Counties across the nation and the first in Pennsylvania who are using the Stepping Up suggested three step approach which includes establishing a shared Serious Mental Illness (SMI) definition across criminal justice and behavioral health systems, ensuring everyone who is booked into jail is screened for a mental illness diagnosis, and regular reporting on this population.

Mental Health Forensic Diversion & Case Management Program in Berks County, Pennsylvania

Forensic Diversion is a program of the Berks County Mental Health & Developmental Disabilities Program (MH/DD) in partnership with Service Access Management Inc. (SAM) to reduce the incidences of individuals with identified and/or suspected mental illness from being incarcerated, reduce lengthy stays of incarcerations due to lack of supports, and decrease recidivism and/or police contact after release from higher levels of care. The Diversion team consists of the individual served, MH/DD, Diversion Specialist and Forensic Blended Case Manager, Criminal Justice Agencies (Police, District Attorney, Jail, Probation/Parole, and Public Defender), mental health agencies, and family members.

The Diversion Specialists (both licensed clinicians) meet with individuals to determine if they are appropriate candidates for services. Appropriateness for services is defined as a person living with the following: mental illness diagnosis, current criminal justice involvement, and reduced imminent risk to the community. If an individual is deemed appropriate for a diversion plan, the Diversion Specialist will make recommendations to the Courts as to specific conditions to reduce and/or eliminate charges. Some conditions may include; stipulated treatment compliance, compliance with medication management, participation is assigned community wellness programs, and oversight with mental health case management supports. Most commonly, these stipulations are regulated with unsecure bail conditions which are then monitored through Pretrial Services. Forensic Blended Case Managers (FBCM) monitor compliance to the Mental Health Forensic Diversion Program and meet weekly with individuals on an active diversion plan. If conditions are not followed and the person is not engaging in services, bail can be revoked, and further criminal charges pursued.

Within the past 2 years, the Mental Health Forensic Diversion Program (MHFDP) in Berks County expanded to include 17 one bedroom, fully furnished Forensic Housing apartments in partnership with another local treatment provider to address the issue of homelessness that many individuals face. Every individual who is accepted into the Forensic Housing program works with a housing case manager through a contracted agency as well as a FBCM through SAM.

The goal of FBCM is to assist individuals, both currently in the penal system and former inmates, to connect to the system of supports and programs available that help them achieve their wellness and recovery goals. FBCMs meet with individuals within the county jail system to determine eligibility for case management, assess individual’s needs, and develop goals prior to their release. Forensic case managers also assist released individuals to access appropriate community resources and coordinate mental health services.Sequential Intercept Model

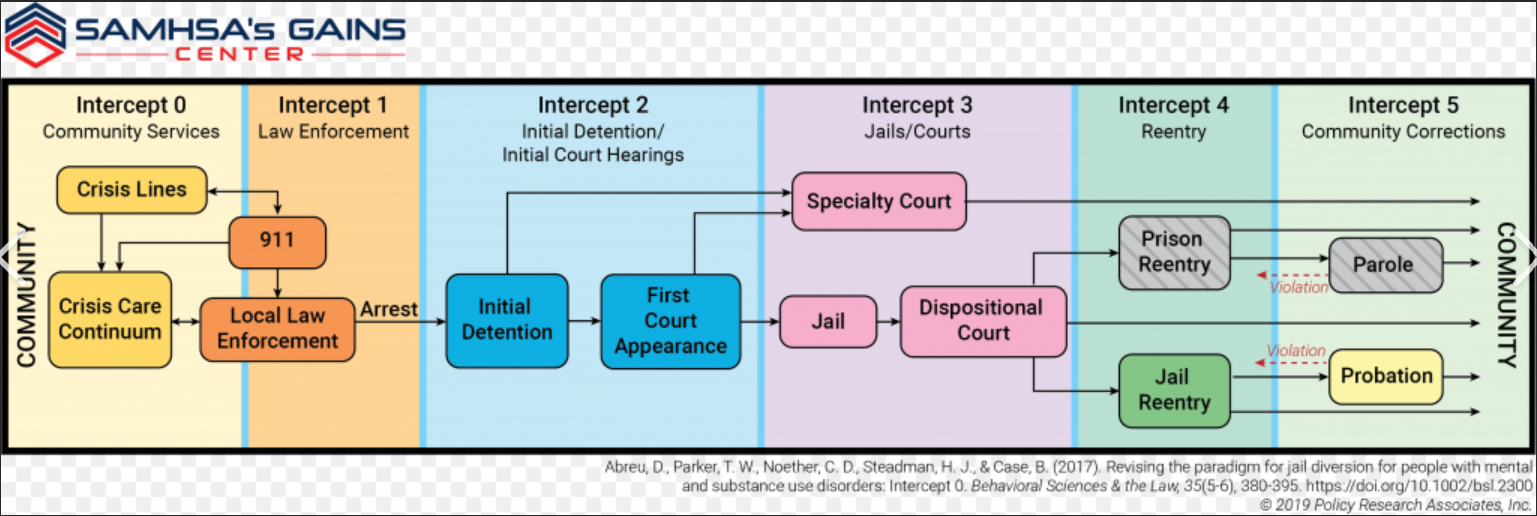

As stated above, individuals with mental illness are overrepresented in jails and prisons. It has been our program’s observation that correctional facilities are not intended to be mental health treatment facilities and are unable to service in this capacity. In addition to mental health symptoms worsening during incarceration, individuals experience a disruption in treatment as well, if they were receiving community-based treatment prior to their arrest and detainment. The Sequential Intercept Model (SIM) outlines several points at which a person with mental illness can be “intercepted” and kept from going further into the justice system (see Chart 1 below). Berks County’s Diversion Specialists utilize the SIM for every diversion. Six different intercepts have been identified by the SIM: Intercept 0: Community Services encompass the early intervention points for people with mental health issues before they are arrested and involves other agencies outside of the justice system such as Crisis Intervention services; Intercept 1: Law Enforcement and/or other first responders are often the first to encounter an individual experiencing a mental health crisis. This intercept includes all pre-arrest diversion options and concludes when someone is arrested; Intercept 2: Initial Detention/Initial Court Hearings include post arrest diversion options which include treatment instead of incarceration or prosecution. Strategies are used at this Intercept to screen for mental health issues, divert individuals through pre-trial services for low level offenses with treatment; Intercept 3: Jails/Courts concentrate on individuals who are being held in pretrial detention and are awaiting disposition of their criminal case(s). Specialty treatment courts may be offered at this intercept; Intercept 4: Reentry addresses continuity of care between the jail system and mental health providers in the community; and, Intercept 5: Community Corrections includes probation and parole and offers alternatives to technical violations that would usually result in jail time. Diversion specialists can engage an individual with mental illness at any one of these six intercepts.

Chart 1. Sequential Intercept Model

Berks County Mental Health Forensic Diversion Program Overview and Case Studies

The Berks County Mental Health Forensics Program was developed January of 2011. Its initial growth came from a collaborative joint effort between Berks County’s Office of Mental Health and Developmental Disabilities (MH/DD) and the county’s pre-trial service provider with a preliminary focus to offer diversionary assessments and evaluations for defendants at the Common Pleas Level of pretrial judiciary commitments. With an initial purpose to integrate diversionary supports and options that would serve as alternates to incarceration of the “mental health forensics” population, early findings concluded that a broader scope of what a mental health forensics population would need to be redefined.

As the program developed and more focus was on redefining the mental health forensic population, it became clear that more intercept and diversionary efforts were needed at the arresting intercept point. Berks County quickly began a course of mental health forensics training, education, collaboration, and communication with all judiciary, criminal, justice, law enforcement, and mental health stakeholders. Numerous levels of intercept mapping were developed to help assess where the largest need was present and to intercept non-imminent risk mental health arrests, provide jail diversion at the pre-arrest point, and decrease non-imminent risk defendants at the magisterial district court and arraignment intercept points. It is with these intercept points of recognition that the Mental Health Forensic Diversion Program (MHFDP) was created and implemented real time psycho-forensics assessments at the arresting intercept point.

Berks County’s MHFDP quickly became a resource for Berks County’s 42 different law enforcement departments. The police department’s reception of the MHFDP was nothing short of outstanding. By offering the police departments a specialized program that increased police officer awareness and training in dealing with mental health contacts, the number of incarcerated, low-risk mental health offenders decreased.

To date, 633 mental health forensics diversions over the past eight years have been completed including 326 police encounters interventions and only 33 cases of re-arrest by diversion clients while in the program. Finally, the most impactful and prideful fact, of the 326 arrest point diversions with police, only twice did a police officer disagree with the recommendations at two separate intercept points. This demonstrates the exceptional quality of collaboration, community support, and citizen empathy that occurs when varying county offices are in complete agreement with and understand the need to improve mental health supports.

Below are two case examples that will highlight our programs efforts in supporting the mental health forensics population.

Presentation of Mental Health Forensic Diversion Intercept Point Case Examples

Case Example I: John Doe Mental Health Forensic Diversion Intercept Point 3(A2)

Mental Health Forensic Intercept Narrative (A2) for John Doe

Berks County Mental Health Forensics Program received a contact from a rural police department in Berks County asking for a diversion specialist to complete a psycho-forensic evaluation for diversionary options on scene where several imminent risk factors are present: self-harm, threats of harm, weapons, and aggregated assaultive behavior. The Police Officer on scene also reported that, despite the imminent risk threat, he is concerned that John Doe may have underlying mental health concerns, and that jail may not be the most appropriate level of care for John Doe.

Mental Health Forensic Presenting Narrative (A2):

The psycho-forensic diversion specialist arrived on scene to a moderately secluded single home in a rural township of Berks County. On scene were five police officers, two EMT’s, and two firefighters. Along with the first responders are John Doe, his mother, father, brother, and four on-looking neighbors. The time of day was approximately 8:30pm on a Friday in late summer. The home was clean but unorganized.

The police officer reported that John Doe and his sibling engaged in a physical altercation, of which John Doe threatened to kill his brother with a knife. The police officer reported there have been multiple calls to the home for similar complaints and added that there is a history of marijuana and alcohol use in the home and by the brothers. It was also reported that John Doe had written $5,000.00 worth of fraudulent checks from his father’s checking account. John Doe used the checks to purchase a cache of firearms, parts, and accessories. The police reported no known criminal behaviors to harm others or threats of illicit weapons usage.

In meeting with John Doe’s mother and father, both report an exacerbated history of mental health treatment and medical concerns. They reported that John has been diagnosed with various mental health disorders over the past four years and that John Doe displays erratic and psychotic type behavior. The parents reported that John has active charges pending in another county for a DUI, trespassing, and damage in excess of $1,000.00. These charges were a result of John becoming agitated and aggressive after an altercation with his brother over a video game which led John to consume alcohol and smoke marijuana, which led to him crashing his car into a local grocery store. His mom reported that behavior as being out of character for him.

During conversation, his parents reported that they have been divorced for three years. They described their relationship as poor at best and the family’s typical home life is unhealthy and unsupportive. Dad reported that John’s grandfather is an avid gun collector who taught John about the craft of making firearms. Dad continued to report that John is a marksmen on several area shooting clubs and that John possesses the ability to hit a bullseye from 300 yards away, and that he was very concerned as John decompensates more frequently. It was explained that John was a straight A student as a high school sophomore three years ago. John suffered a concussion from football three years ago and that they noticed depressive fugue type states. Additionally, John experienced three more concussions since his sophomore year in high school and the concussions went primarily untreated; although, he did seek medical attention via area emergency departments.

Brief Real Time Psycho-Forensic Assessment (A2)

A real time psycho-forensic assessment was conducted on scene to determine the motive of criminal behaviors, psychopathology, and imminent risk. Upon meeting with John, it was evident that he was experiencing acute features of anxiety, instability of thought, and mild depressive features. His overall presentation was best described as engaging in posture, articulate of content, and distracted in reality-testing. He did not present any psychotic features or expressions of self-harm. He was easily distracted by the overall energy surrounding the current intervention. He reported acute and heightened anger feelings and thoughts as explained by John: “sometimes I get like this and I don’t know why, my brother really did nothing wrong. I just get so angry and I can’t control it.” He continued to state, “I don’t hear voices, I don’t usually feel out of control, I never want to hurt anyone. Just I get this feeling when I can’t think right. Like my brain is out of control.” John reported an extensive history of acute, unprovoked angry states. He described these states as out of his control and reckless. John reported some drug use with marijuana and minimal alcohol use, which began about 2 years prior.

As the conversation continued, John maintained a cooperative and engaging tone and posture. He appeared labile for the most part of our conversation, and was talkative and expressive; however, his mood was flat. He continued to state, “I probably would have killed my brother and I have no idea why. I just get so angry I don’t know why.” When asked about the cache of firearms parts he purchased with his father’s blank checks he replied, “I don’t know what I was going to do with them, probably nothing good.”

It is also noted that John’s family offered the following information: John had multiple concussions that were untreated the past four years, he had numerous mental health interventions and treatment with minimal success, John is highly intelligent and had full academic scholarships to three universities, and he has displayed unprovoked aggressive and dangerous behaviors multiple times since his first concussion.

The following recommendations were made as a result of the assessment and rationale: detainment to jail on the current charges was needed to eliminate any imminent risk and provide a level of safety for John and the community, of which he would not receive in an inpatient mental health facility. John presented with several Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) markers that lead this writer to rule out mental health primary concerns; due to this, an inpatient psychiatric admission would serve no current purpose. Exploration of adequate treatment options for John’s underlying traumatic brain injury pathology would be determined while decreasing all imminent risk possibilities.

Based on forensic diversion recommendations and after consultation with the arresting police officers and the Berks County District Attorney’s office, John was detained at jail. Subsequent diversionary actions began to explore a level of adequate treatment for John related to TBI pathology and treatment.

Jail-Based Diversion Planning (A2):

John was placed in a single cell on the jail’s medical unit. During several meetings and assessments with various providers and professionals, John continued to display excellent compliance with all jail programming, willingness to learn about his mental and cognitive concerns, and an excellent level of investment into stabilizing his impulsive and unexplained anger outbursts. He stated, “I just feel that sometimes my brain loses track of what I’m doing and makes me so angry. Like I can be reading about history and all of a sudden, I want to hurt someone. I don’t hear voices, it’s like a switch just flips.”

John continued to report TBI type effects while in jail and during the time the diversion specialist met with him at the jail to build rapport. He stated, “My head just hurts sometimes, I get headaches all the time. I throw up without warning. Flickering lights cause so much pain in my head.” John started reporting these symptoms during the first meeting while he was in jail. It was evident that his TBI pathology was his primary health concern and that there are no mental health markers that should be considered at that point. From a pathology of behavior understanding, it became clear that John needed TBI and Cognitive Rehabilitation supports and not psychiatric intervention.

The forensic team started a course of research into TBI and Cognitive Restorative Programs in Pennsylvania which uncovered a new State funded program for “Early Onset TBI Rehabilitation.” This program is grant funded and awarding of the state grant requires several levels documentation that included historical and demographic information, current assessments, medical TBI evaluations, social relationships, and academic performance. The team quickly prepared the referral packet and began the referral process. After approximately two weeks, the referral packet for TBI state programming was accepted and the residential program director of TBI Rehabilitation agreed to meet John at the jail. The program director and her team conducted four separate assessments with John while he was in jail and it was determined that John was an ideal candidate for TBI Rehabilitation. They agreed to award him a grant of $200,000.00 for 16- month admission into their TBI Cognitive Rehabilitation Residential Program (CRRP). His official acceptance and move-in to the program would occur in about four months.

Once the team received confirmation of John’s acceptance into the CRRP, the district attorney and John’s legal defense were notified. It was recommended that John remain in jail for the next three months to continue his course of stabilization with jail-based reentry programming and that John be released one month prior to the CRRP admission and admitted into the Mental Health Forensic Diversion Housing Program (MHFHP). The goal for his admission into our MHFHP was to prepare John for re-integration into a program-based setting while under a supervised supportive structure.

The district attorney’s office, John’s legal defense, and the judge agreed with the recommendations of the forensic diversion specialist. An unsecured bail plan was filed, and John was ordered to comply with all diversion conditions of the bail plan.

Unsecured Bail Diversion Plan (A2)

John was released from jail approximately three months after his arrest for charges of aggravated and simple assault, harassment, possession and administration of fraudulent checks, possession of illicit firearms in excess of $5,000.00, and terroristic threats. He was placed on unsecured bail and the charges were to be held for continuance through his admission into Berks County’s Mental Health Forensic Program.

John’s unsecured bail conditions-based diversion recommendations were as follows:

For one month, or until admission into the CRRP, you will comply with all conditions of your bail:

1. Maintain compliance with all the rules and conditions of the MHFHP

2. Maintain compliance with all of you outpatient treatment requirements

3. Begin a course of peer support

4. Begin participation with Berks County’s Forensic Mental Health Case Management Program

5. Begin pre-trial supervision until your admission into the CRRP

While in the MHFHP, John maintained exceptional compliance, ongoing eagerness to stabilize his health, and significant initiation in life goal achievement, behaviors of motivation towards rehabilitation, and insight into his own pathology as affected by TBI. John was able to live in an independent living setting and comply with all re-integrative supports during the one-month admission into the MHFHP.

CRRP Admission and Dismissal of Charges

John completed the one-month re-integrative condition of his unsecured bail. He was then admitted into the CRRP. All of his charges were dismissed at this point and he was not convicted on any of his original charges.

John was admitted and living at the CRRP which is approximately ninety minutes away from his residence. He was in the CRRP for about four months where the focus is on long term cognitive rehabilitation treatment for early onset TBI individuals. John is now connected to a team of professionals as he lives independently in a CRRP apartment. To date, John has displayed exceptional improvement during his rehabilitation process. He no longer carries any psychiatric diagnoses and his only active medical diagnosis is Early Onset TBI.

John’s immediate goals for the future are to re-enroll into college, continue his road to TBI understanding, independent living, and becoming an advocate for TBI awareness among our youth.

Case Example II: Jane Doe Mental Health Forensic Intercept Point 2 (A2)

Mental Health Forensic Diversion Intercept Narrative for Jane Doe

Jane Doe was referred to the forensic diversion program by a mental health case management provider who asked for a diversion assessment for her client. The Blended Case Manager (BCM) reported that Jane has an upcoming trial for theft of $55,000.00 from a non-profit social club where she volunteered to manage the financial records and related charges. Jane was referred to us at pre-trial intercept point of diversionary intervention.

Jane’s diversion narrative consists of several layers of mental health, criminology, and pathological behaviors that exacerbated her ability to formulate healthy and rational decisions in the 16 months leading up to her arrest. Her case manager reported that Jane was employed for numerous years as a financial auditor for a private business, but that she consistently struggled with her mental health stabilization, thus the need for case management services.

Her BCM continued to discuss that Jane is morbidly obese, lived in isolation, had poor physical mobility, few social contacts, and a chronic feeling of suicidality. It was reported that Jane was active in treatment; however, it was difficult for her to manage consistent appointment attendance and commitments due to her limitation with transportation and the distance her current residence is from nearby towns and cities.

Jane’s case presentation for referral at the pre-trial intercept point was atypical. Generally, the forensic diversion program does not address theft charges in this range as a precautionary factor in dealing with monetary bail conditions. However, it was in the best interest of Jane that the diversion specialist consulted with the assistant district attorney (ADA) assigned to the case. Knowing the ADA is an advocate for mental health criminal justice support, a diversionary plan that offers support and other options was presented. This consultation was before the diversion specialist met Jane, but based on the reliability of the BCM’s relationship with her and the overall extent of her crime, there was a need for an immediate consult which was done in an effort to save time and/or rule out any denial of such plan for related crimes. The ADA reported that Jane is facing numerous federal and state charges. He stated the federal charges would most likely be dismissed at the pre-trial level, but Jane would still face serious charges with the likelihood of extensive jail time. The Diversion Specialist offered consideration to assess Jane and determine an underlying mental health pathology that could rule out any motive to commit such crimes. Based on Jane’s referral presentation, Jane’s quality of life was presented to help the court make conclusions as to any level imminent risk she would present to the community. The ADA agreed to hold the charges for continuance of one month until a full assessment could be completed and recommendations made to the court.

Initial Referral Our Program

The Diversion Specialist met with Jane two days after receiving the initial referral from her BCM. Jane, her BCM, and a diversional specialist met at Jane’s home for approximately three hours. This was to conduct a MHFDA in order to rule out motive and to support any exacerbated mental health pathology as the driver to her crime.

Mental Health Forensic Diversion Narrative

Jane presents as morbidly obese and physical limited in mobility. She required a walker to help move throughout her apartment. Jane appeared moderately hygienic and there were some concerns with her ability to maintain herself and her home. However, this could be due to her obesity and limited mobility.

Jane reported that she has been in mental health treatment her whole life and added that her life has been marred with significant trauma, abuse, neglect, and minimal supportive networks. Jane reported that as she aged, she did develop more supportive friendships. She continued to report that she has always held employment and believes in working hard to be a responsible citizen. Jane reported only a high school education but that she has developed a skilled set in tax preparation and financial records administration type services.

Brief Real Time Psycho-Forensic Assessment and Evaluation

Jane reported the last three years have been very difficult as her weight increased and she became less mobile. She mentioned the difficulty she had in getting to work regularly and subsequently earning an income relative to her daily living needs. It was also around this time that she started playing video gambling games on the internet. Jane reported these games cost money and she started paying to play. It was also at this time that she volunteered at a local non-profit social hall to help manage the finances. Jane reported the past three years she became addicted to video gambling and subsequently funded her addiction by stealing funds from the social hall. She was able to detail each occurrence of theft, the amount of each theft, and what the stolen funds covered in way of her addiction and daily living needs.

Upon presentation, Jane appeared labile, moderately depressed and with mild anxiety type features in mood and affect. She was open to discussion but guarded with personal and historic questioning. Jane displayed concerns with a poor lifestyle of wellness and with moderate concerns of hygiene. She reported, “I have not cared about my weight and health for a long time. I have been so depressed and angered about my trauma and terrible family supports. I just let myself go”. She does not present any psychotic features and she is orientated to person, place, and time. She is an intelligent, elderly woman in her 60’s that does display quality of insight and rationalization. There were no cognitive or thought disorder concerns. Jane reported several areas of social relationship isolation and an inability to form adequate emotional relationships. She reported, “I have lost complete trust in any one person to care and love. I have no one, and everyone in my life has abandoned me or taking advantage of me. I was abused atonally, bullied often, and ignored by kids as a child and later by adults. So, I just don’t know how to form good friendships that I can trust.” Jane presented as a survivor of abuse to some form on an emotional level. Her overall personality is like a depressive type personality disorder. When asked about the gambling abuse and theft of the funds, she stated, “I am addicted to those games, it’s the only thing that makes me feel something. I feel in control. I started stealing the money knowing I would get caught. But I didn’t care. I didn’t want to feel depressed anymore, those video games and gambling helped numb my depression and my abusive past.”

At the conclusion of the assessment, it appeared that Jane was living with some form of a personality disorder, possibly a depressive type. This personality disorder most likely developed as a behavior need to survivor and cope. Her overt behaviors say addiction; however, when the layers of her pathology are removed, it was concluded that Jane is in emotional despair.

Based on the assessment, it was recommended that Jane be considered for acceptance into the diversion program. Jane would not benefit from being in prison, a diversion from a prison sentence would serve to help Jane become a contributor to society by paying restitution and improving her overall quality of life.

Mental Health Forensic Diversion Plan

Recommendations were made to the ADA, Jane’s legal defense, the victims, and the presiding judge for Jane’s case. Based on Jane’s overall level of poor health, her underlying features of marked abuse and neglect, her willingness to comply with treatment, her ability to pay full restitution, and the conclusion that her motive was not to steal money, but rather to not feel her depressive pathology. Jane needed to cope with her pathology, she endeavored to a place of addiction as means to feel. Understanding the crime itself is significant, her behavior in the crime would not serve to help Jane return to society after a lengthy prison sentence.

Jane’s case presented with numerous

variables, of which diversion has not historically offered to support in the

past. It was clear Jane did not have a criminal motive, she was not an imminent

risk to society, and she was genuinely willing to offer full restitution. Jane

was facing numerous charges, of which carry a minimum sentence of 6-8 years in

state prison. I presented the following recommendation for Jane’s diversion

from a conviction and sentencing to state prison:

1. Agree and comply with all recommendations at the point of agreed continuance of your charges to unsecured bail.

2. Agree and comply with all conditions upon your admission into the Berks County Mental Health Forensic Transitional Housing Program offered through our program.

3. Agree and comply with all recommendations upon admittance into our county’s Intense Outpatient Program (IOP) and Addiction Treatment Group.

4. Agree and comply with all recommendations upon your admission into our county’s mental health treatment court program.

5. Agree to pay 75% of the restitution with in the first year and the remaining 25% of the restriction with in the second year.

6. Agree and comply with all treatment recommendations upon admission into our Wellness/Lifestyle Program.

7. Agree and comply with all psychiatric medication management recommendations upon admission into our Psychiatric Outpatient Program.

8. Agree and comply with all recommendations by your step-down provider upon completion of the IOP.

9. Agree and comply with all services offered through SAM, Inc. upon completion of the intake.

10. Agree and comply with all recommendations provided by your peer specialist.

11. Agree and comply with all recommendations made by the Mental Health Forensic Diversion Program.

12. Agree and comply with all recommendations upon admission into our Job Readiness Program.

13. Agree and comply with all treatment recommendations made by your entire support team.

The victims, Jane’s legal defense, ADA, and the presiding judge all agreed to support Jane with the recommended plan. Jane was placed on unsecured bail and ordered to comply with the above plan. She also had status hearing checks in court every two months for the next year. If she maintains her compliance for the next year, she will only be convicted of a much lesser charge and never set foot into a prison.

Diversion Outcome

Jane was able to comply with the entire plan for one year and was able pay full restitution back to the victim over the course of 18 months. She gained meaningful employment and started living a life of wellness, independence, and recovery. Presently, Jane is living independently and recently completed her last cycle of mental health treatment court. She has only received one conviction of a summary offense.

Jane’s case offered a moment to really pay attention to what drives overt criminal behavior—often taking time to listen, the person can be understood, and services are not fixated on the crime. When the layers of a person’s criminal actions are peeled away, and time is taken to learn what drives such behavior, then more help can be offered as opposed to incarceration. Jane’s case was a complete stretch to support based on her theft and its amount. This is an excellent example of the judicial system working to help and not incarcerate.

Conclusion

Throughout the past several years, the forensic diversion program has offered individuals with mental illness and criminal charges an opportunity to engage in treatment to address their mental health concerns and/or other concerns that directly affect their behavior and interactions with others. The case studies presented above are just two examples of this program’s success.

Our success is a direct reflection of the collaboration of our county’s stakeholders shared with the development of our program. The impact of this collaboration has born significant fruit in continuity of care. The continuity to foster support for this population among all stakeholders, public office, law enforcement departments, and treatment providers is a direct reflection of the regard each office has for the mental health population.

To continue our program’s goals of collaboration and continuity within the mental health forensics population, our team conducts law enforcement trainings, presents at national conferences, provides community education, and continues to engage our citizens about the desensitization of the mental health population.

References

- Council of State Governments Justice Center. The Stepping Up Initiative: The Problem. 2020. https://stepuptogether.org/the-problem. Accessed March 16, 2020.

- Council of State Governments Justice Center. Improving outcomes for people with mental illnesses involved in New York City’s criminal court and corrections system. 2020. http://csgjusticecenter.org. Accessed March 16, 2020.

- James D.J, Glaze LE. Mental health problems of prison and jail inmates. Bureau of Justice Statistics. 2006. https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/mhppji.pdf. Accessed March 16, 2020.

- Fisher WH, Roy-Bujnowski KM, Grudzinskas AJ, Clayfield JC, Banks SM, Wolff N.

Patterns and prevalence of arrest in a statewide cohort of mental health care

consumers. Psychiatric Services. 2006;57(11):1623-1628.

- SAMHSA (no details)

- Christie A, Clark C, Frei A, Ryerson S. Challenges of diverting veterans to trauma-informed care: The heterogeneity of intercept 2. Criminal Justice & Behavior, 2012, 39:461-474.

Appendix 1

Tracking Statistics: Programs Inception through March 2020

Referral

Source Tracking Statistics:

· Total # of Referrals: 1112

· Referrals from Police: 398

· Referrals from Courts: 376

· Referrals from Jails/Prison: 244

· Referrals from Family, Agencies, Hospitals, Others: 94

Diversions Tracking Statistics:

· Total # of Diversions from Mental Health Forensic Intercept Points: 626

· Total # of Diversions at Intercept 0 (A2): 326

· Total # of Diversions at Intercept 1 (A2): 98

· Total # of Diversions at Intercept 2 (A3): 84

· Total # of Diversions at Intercept 3 (Detainment/Jail/State Prison): 118

· Total # of Diversion Referrals (Criteria not met): 486

Total Charges & Convictions Diverted from:

· Total Charges (summaries, misdemeanors, felonies): 1408

· Total Summaries Diverted or Dismissed: 821

· Total Misdemeanors Diverted or Dismissed: 433

· Total Felonies Diverted or Dismissed: 154

Total Re-Arrest and/Recidivism

· Total New Arrests: 33

· Total Arrests while in the diversion program: 17

· Total Arrests after completion of diversion program: 16

Appendix 2

Berks County Mental Health Forensics Program

Definition of Terminology Commonly used in our Program

1. Brief Real Time Psycho-Forensic Diversion Evaluation and Assessment: Our programs clinical interview that concludes a contact referrals likelihood to present imminent risk based on mental health diagnosis and symptoms. Based on the contacts presentation during our programs interview we will determine if the contacts current behavior is based on exacerbation of mental health pathology or if there is a criminal motive for which contact is presenting.

2. Jail Based Diversion Planning: Based on our programs assessment and evaluation we conclude the contact would be better served in a treatment program specified to their current mental health pathology, thus diverting them from jail. Our program then prepares recommendations to the court for the court’s ruling on diverting the person from jail and into a specified treatment program.

3. Mental Health Forensic Diversion Contact: Any person who is referred to the program at any of the four intercepts points of diversion.

4. Mental Health Forensic Intercept Point 0: Any diversion referral provided through Family, Supports, and/or police prior to an arrest.

5. Mental Health Forensic Intercept Point 1: Any diversion referral provided at an arraignment or arrest point of intervention.

6. Mental Health Forensic Intercept Point 2: Any diversion referral provided at the pretrial, sentencing and/or conviction point of contact.

7. Mental Health Forensic Intercept Point 3: Any diversion that occurs at the detainment, local jail, state prison and federal incarceration point.

8. Mental Health Forensic Diversion: Any effort made to support an individual living with a mental health disorder and their transitioning from one of the four intercept point and into treatment-based program, all the while removing the likelihood on continued criminal justice involvement

9. Mental Health Forensic Intercept Narrative: The referral sources initial observation, information, and/or concerns for the referral at the initial point of contact

10. Mental Health Forensic Presenting Narrative: The Mental Health Forensic Diversion Specialist initial discussion of the contacts global and historical personal information as relevant to their involvement at the presenting intercept point.

11. Unsecured Bail Diversion Plan: Based on our programs evaluation and assessment we recommend the person be placed on a bail plan which rules the person is to comply with our program’s recommendations for an unspecified period of time. The unsecured bail plan carries no monetary responsibility to the person, but conditions of compliance.

Biography

Jillian Gosselin, MSW, LSW, CPSS, is a Diversion Specialist and Forensic Blended Case Management Supervisor at Service Access & Management, Inc., Berks County, Pennsylvania. She has worked to further develop the Forensic Mental Health Diversion Program, with Mr. Brandon Sands, as well as develop and expand case management services specifically for the forensic mental health population. Ms. Gosselin graduated from Albright College with a Bachelor of Arts Degree in Psychology and from Marywood University with a Master’s Degree in Social Work. Over the past 17 years, Ms. Gosselin has presented at National and International Conferences in various topics including mental health, drug and alcohol, sex workers, prevention of high-risk behaviors among youth, and HIV prevention.

In addition to her work in the behavioral health field, she continues to work as an independent consultant, writing grant proposals, analyzing data, and working with a highly qualified evaluation team for federally funded substance abuse grant programs focusing on at-risk populations. Ms. Gosselin also works as a Peer Reviewer for SAMHSA grant applications. In previous years, she has worked as an Adjunct Professor of Psychology at Albright College in Reading, Pennsylvania.

Ms. Gosselin resides in West Reading, Pennsylvania with her husband, Mark, and 10-year-old daughter, Sara. In her free time, she enjoys spending time with her family and playing soccer in a competitive women’s league.

Contact Information:

Jillian Gosselin, MSW, LSW, CPSS

Diversion Specialist and Forensic Blended Case Management Supervisor at Service Access & Management, Inc

(484) 987-5321

Biography

Brandon Sands, LPC, NCC, CABA, CPSS has assisted in the development of the Berks County (Pennsylvania) Mental Health Forensic Diversion Program. Over the past 10 years, he has implemented specific psycho-forensic parameters to assist in the diagnosis, treatment and reintegration of the Forensic Mental Health Population. He speaks nationally on various topics regarding the training, treatment, education, development and psychopathy of the Mental Health Forensic population. Mr. Sands, along with Ms. Gosselin, have developed specified restoration and reintegration services, guidelines, programs and initiative to assist with national awareness and training for those providing any level services and support for this population.

Along with his work in the psycho-forensics field, Mr. Sands is also an Adjunct Professor of Psychology for the past 17 years at Alvernia University. He is partner in a private practice that serves five counties in Pennsylvania. In private practice, his treatment focus is primarily with clinical, testing, sports, anxiety, and behavioral-related areas of practice. Mr. Sands is a Licensed Certified Applied Behavioral Analyst that provides various testing, diagnosis, and treatment services for the Intellectually Disabled populations.

Contact Information:

Brandon Sands, LPC, NCC, CABA, CPSS

610-763-8537

Basands1@icloud.com

Hooven | 55-61

Volume 9 ► Issue 1 ► 2020

Interactions with Law Enforcement and Individuals with Autism

Kate Hooven

Abstract

The Center for Disease Control reported in March,2020 that the rates of autism have increased from 1 in 59 to 1 in 54. With the rates continuing to rise, so too will the interactions of individuals with autism and law enforcement. The circumstances and the outcomes of these incidents will vary, but, one thing will remain constant, the need for training and education for both the law enforcement community and individuals with autism in order to increase safety and more positive outcomes. Here is one mother and her teenage son’s story.

I saw the police car discreetly tucked under a tree on a country road. I knew without even looking at my speedometer that I was going to meet the officer sitting in that police car in person, and soon. Sure enough, within a few moments I was proven right. I saw the officer’s car pull out from under the tree. My eyes kept darting from the road in front of me to my rearview mirror, knowing full well what was coming behind me was almost as important as what lay ahead. Then, the lights, the siren, and perhaps a word or two one shouldn’t say in front of their kids.

Taking a deep breath to calm myself, I pasted on a smile and said, “Hey kids, I think mom is about to get a speeding ticket.” There were the expected shrieks of, “What?” and “Are you going to go to jail?” along with the shaking fear that many of us exhibit when those red and blue lights pull up behind us. I tried to calm my children’s fears by letting them know that I was not going to jail, and that mommy may have been going a little over the speed limit and that at most I would get a citation, a speeding ticket.

As I glided my car to the side of the road, I assured my 16-year-old son teenage son sitting next to me that it would be fine, but, he did not look as though he believed me. In fact, I don’t think my son heard a word I said because he had already gone into complete shut-down mode. My son has autism. This kind of disruption, this kind of interaction with law enforcement was certainly not part of his normal routine and if there is one thing my son craves, it is routine. He was terrified.

After I provided the police officer with my license and registration, the officer tried to joke with the kids about their law-breaking mother. A nervous giggle escaped from my daughter seated in the back of the car, but, my son, seated in the passenger seat, sat stone still, face down staring at the floor mats with no response. My son acted as if he hadn’t heard the officer when the officer directed a question at my son. He did not acknowledge the officer, he did not smile, he did not take his eyes off the car floor mats. I know full well had I not been there to say, “My son has autism and he is really, really nervous right now” that simple speeding citation could have ended much differently.

Although verbal, in that moment of such heightened anxiety, my son was unable to form the words, “I have autism.” My son does not carry any kind of autism identifier he could have shown police; however, he does wear an autism awareness bracelet. But, prior to this incident, we did not discuss what to do and what not to do, if stopped by the police. If I had not been there to advocate for my son, his autistic behavior to an untrained police officer may have looked like non-compliance. My son’s lack of eye contact could have led that officer to believe that my son was lying or keeping something from him. Worst yet, had the lights and sirens overwhelmed my sensory sensitive son to the point his sensory system could no longer handle such an onslaught of stimuli, he might have jumped out of the car and ran to escape those sensations which could have had dire consequences.

None of that happened because I was there to advocate for my son, who, as I mentioned, is completely verbal but unable to communicate in times of stress. My son’s inability to communicate his autism diagnosis to the police officer is not unique to him. Many individuals with autism have communication deficits or communicate in a different manner, a manner many of our law enforcement officers are unaware of if they have not been properly trained. This leaves both the individual with autism and the officer at a disadvantage that could have negative outcomes for both.

For example, had I not been present and able to advocate for my son, a trained police officer may have recognized my son’s silence and his lack of eye contact as signs of autism. Subsequently, the officer could have asked, “Do you have autism?” And although my son may not have been able to verbally say, “yes,” he could have nodded his head which would have given the officer the information he needed to move forward safely. My son and I have since had multiple discussions on what my son should have done and what he will need to do if there is a next time. One of the first things my son will do if there is a next time, is point to his autism awareness bracelet if he is unable to form the words, “I have autism.”

This was one incident, for one individual with autism, but we continue to hear about similar stories on the news and in other media outlets that these type of incidents are occurring with more regularity and sometimes the outcome is positive, but sometimes it is not. The one variable that seems to make a difference in these types of interactions and ensuing outcomes with law enforcement and individuals with autism, is awareness and training. How can we expect our law enforcement officers to understand and respect our individuals with autism, if we don’t educate law enforcement on the various ways individuals with autism communicate, the types of behaviors they may witness, or provide the officers with tools and strategies on how to safely interact with individuals with autism? And equally as important, our individuals with autism need to understand how to safely interact with law enforcement by learning what to do and what not to do if stopped by police.

For five years, Pennsylvania’s ASERT (Autism Services, Education, Resources and Training) has been providing training to justice system personnel, as well as training for individuals with autism. The positive response and the effectiveness of the training is evident from the stories we are hearing from both law enforcement, as well as, family members of individuals with autism. Four days following an ASERT autism training, two police officers were called to a home where a young man with autism was struggling with escalating behaviors. The mother alerted the 911 operator that her son had autism and “would probably need restrained.” Upon approaching the home, the police officers turned off their lights and siren and contacted the EMS Team who was responding and suggested they do the same. Once they entered the home, the officers asked the mother what her son’s interests were, what his sensitivities were and how he communicated. Thanks to the officers’ understanding of autism following ASERT’s training, the young man was able to walk unassisted to the police car and was taken to a local hospital without incident.

In trainings designed for individuals with autism and their family members, an ASERT team member and a local police officer spend an hour explaining the importance of following the laws, the role of a police officer and the do’s and don’ts if stopped by police, as well as, sharing valuable resources such as Social Stories ™ to enable our individuals with autism to be better prepared if they come into contact with law enforcement. These type of trainings not only benefit the audience member, but they also make the local officer who participates more aware as he/she is able to interact with these individuals with autism when they are not in a crisis situation which is invaluable. ASERT has provided in-person training to over 8,000 law enforcement and first responders as well as 1,400 participants in virtual trainings. The trainings are free and can be tailored for time and content, depending on the needs of the audience. All trainings are comprised of three content areas; clinical overview of Autism Spectrum Disorder including core deficits and symptoms, Statewide Data from the Pennsylvania Autism Census and the Statewide Survey of Justice System Professionals and how to practically apply information learned to everyday job duties. The training can be completed in person or virtually.

We cannot expect our law enforcement community to know the signs of autism and how to safely interact with individuals with autism if we don’t provide them with the information and the tools and strategies to do so. The same holds true for our individuals with autism. They must learn what to do and what not to do if stopped by police in order to keep them safe. The education and the awareness go both ways.

As

a mother, my greatest job is to love and protect my kids. I taught them about

stranger danger, how to cross the road safely and what to do in case of a fire,

but, until the day I got that speeding ticket and saw my then 16-year-old son

with autism completely shut down, I never had a discussion on what to do if

stopped by police. It is my job to keep my kids safe. It is my job to PLAN

(Prepare, Learn, Advise and Notify) for my kids’ safety, all of my kids,

regardless of age or ability. By educating law enforcement, educating the

community, and educating individuals with autism, we increase the odds that

every time my son walks out our front door, he will come back through that

front door safer, understood and accepted.

Mailloux | 62-72

Volume 9 ► Issue 1 ► 2020

Forensic Peer Support

Services: A Personal Perspective

Jaclyn Mailloux, CPS/Certified Peer Specialist

Abstract