Positive Approaches Journal, Volume 9, Issue 3

Brusilovskiy & Salzer | 12-19

Volume 9 ► Issue 3 ► 2020

Using Global Positioning Systems to Assess Community Mobility and Participation of Individuals with Disabilities

Eugene Brusilovskiy & Mark S. Salzer

Background

Community inclusion and participation are essential for the health of people with disabilities.1 Community mobility, defined as “locomotion in environments outside the home”2 is often needed for community participation.3,4 Global Positioning Systems (GPS) offers a novel approach for understanding the extent to which people with disabilities are getting out of their homes and moving about their communities. The purpose of this paper is to 1) provide a brief overview of GPS tracking, 2) describe mobility variables from GPS data, and 3) briefly summarize some key findings of our GPS research.

Using GPS to Track Mobility of Individuals with Disabilities

There are numerous GPS devices that can be used to track the mobility of individuals with disabilities. Some include handheld GPS transmitters that can be worn or carried, such as watches, keychains, pocket-size trackers, or GPS-enabled smartphones. Data can be downloaded from these devices or sent in real-time via WiFi or cellular transmissions. Data includes latitude, longitude, and sometimes altitude, and tracking can be to the minute, which could lead to up to 1440 data points per day and 10,080 in a week. There are often two major concerns with GPS data collection, briefly described below.

Missing Data Concerns

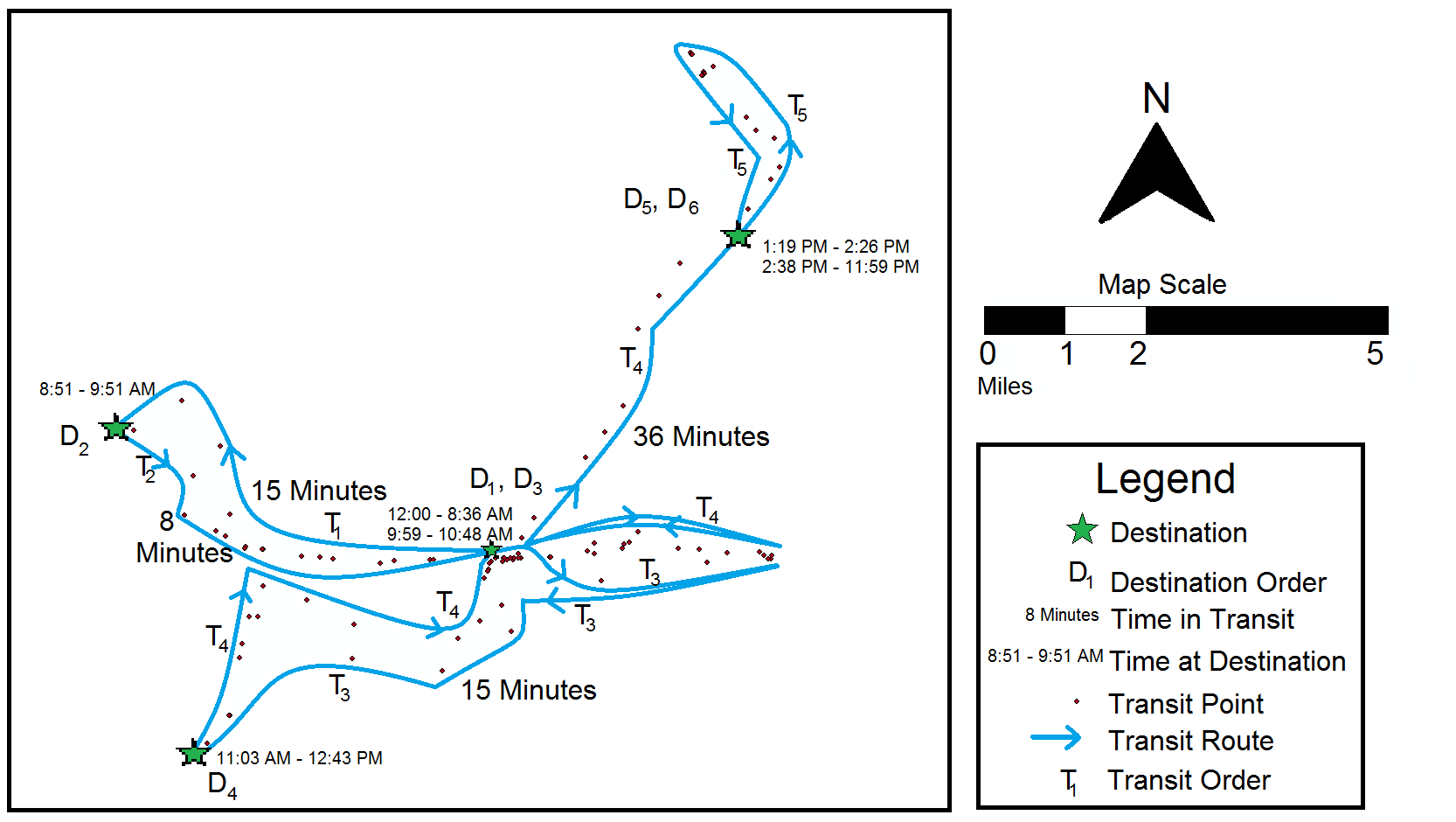

GPS data are messy, and a lot of cleaning needs to happen before any constructs can be computed. For instance, because GPS reception only works when the phone is outdoors or close to a window, when an individual is indoors, GPS data will be missing and will need to be imputed. We developed an algorithm for dealing with missing data which is described in detail in Brusilovskiy, Klein, & Salzer (2016)5. Figure 1 shows an example of what GPS points look like once put on a map with consecutive destinations denoted by D and transit to other destinations indicated by T, along with time stamps.5

Figure 1. Visualization of GPS Data5

Ethics Concerns

Another key concern is the issue of ethics and privacy around GPS data collection. Although GPS tracking may seem intrusive, it is important to keep in mind that only the location is being recorded, and not what the individual is doing at that location, or who she is with. Storing data on a secure, password-protected HIPAA-approved server, and making sure that any maps that are published do not disclose the identity of the participant through reverse geocoding or other means are some additional ways to mitigate privacy-related concerns. Lastly, it is very important to have a detailed consent form which ensures that participants understand what GPS tracking entails, as well as the risks and benefits of participating in the study. In our experience, the majority of individuals with serious mental illnesses and autism-spectrum disorders were interested in participating and did not express concerns about issues related to privacy.

What Mobility Constructs Can We Measure Using GPS?

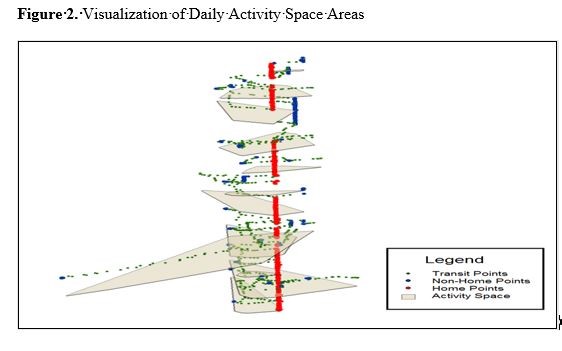

As can be seen in Figure 1, 5 GPS allows us to track numerous things related to mobility, including the total number of destinations someone goes to, number of non-home destinations, and number of unique destinations. This information tells us about how many places people visit and the diversity of places they visit. We can also examine how much time people spend at home and outside of the home, and drill down to time spent in-transit and at each non-home destination. This data can also allow us to calculate the percentage of days they never leave their homes (we might refer to people who spend a large percent of days at home as homebodies) or times of the day when they are more likely to be active outside of the house. Finally, we can examine Activity Spaces, which are defined as “local areas within which people move or travel during the course of their daily activities.” 6,7 Having larger areas to move around may increase people’s opportunities to engage in different types of activities. Figure 2 below shows daily activity space areas for a hypothetical person. Each polygon in the figure represents an activity space for a different day in the study period. The activity spaces in the figure appear to be vertically stacked on one another; this is because in this figure, the vertical axis represents time. Hence, the polygon at the very bottom of the figure represents the activity space for the first day of tracking, the polygon above it represents the activity space for the second day, and so on. Red points show the times that the individual was at home, blue points show the times that individuals spent at non-home destinations, and green points are transit points. This figure enables us to visualize the variability in activity space area by day, as well as the presence of a potential routine if activity space areas on certain days have similar sizes and shapes.

In addition to activity space, we can calculate the total distance they travel over the course of the study period and, for example, the % of days on which the individual traveled distances above or below certain thresholds (less than 1 mile, more than 10 miles, etc.).

What We Are Examining Using GPS

We have carried out several studies which tracked individuals with serious mental illnesses with GPS. One study (Brusilovskiy et al., under review), examines the relationship between the GPS-derived mobility constructs described above and self-reported

measures of community participation. We found that individuals who had more destinations and spent more time out of the house reported greater levels of community participation.

These findings were consistent with the premise that community mobility is a prerequisite for community participation. A second study (McCormick et al., under review), found that spending many more days at home was associated with lower neurocognitive functioning among adults with serious mental illnesses. While it may be the case that neurocognitive functioning may lead people to be more likely to be homebodies, there is substantial research suggesting that environmental deprivation, including possibly spending most of your time at home, can both prevent cognitive development or lead to cognitive decline. A third GPS study,9 examined whether individuals had greater community mobility on days they received services at their community mental health centers. We found that individuals had more unique destinations and time spent out of home on CMHC days than on non-CMHC days, which suggests that scheduling and attending healthcare appointments may have ancillary benefits of getting people out of their homes more. A fourth GPS study,10 shows that individuals who have more destinations and spend more time outside of home have higher levels of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity, lower levels of sedentary activity, and more steps per day. Future studies will look at the relationships between the GPS mobility variables and psychosocial outcomes, physical health outcomes, as well as indicators of the social, built and natural environment.

Conclusions

Using GPS to measure community mobility of individuals with disabilities is an area of increasing interest to researchers, health service providers, and policymakers, for understanding people’s lives in the community. Emerging findings suggest that supporting people in getting out of the house and moving about their community may have positive benefits for their physical, cognitive, and mental health and wellness.

Acknowledgment

The contents of this article were developed under a grant from the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living and Rehabilitation Research (NIDILRR; Grant # 901F0065-02-00; Salzer, PI). However, the contents do not necessarily represent the policy of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, and endorsement by the Federal government should not be assumed.

References

1. Salzer MS. Community inclusion and social determinants: From opportunity to

Health. Psychiatric Services. Rin Press.

2. Patla AE., Shumway-Cook, A. Dimensions of mobility: defining the complexity and difficulty associated with community mobility. Journal of Aging and Physical Activity. 1998;7:7-19.

3. Gattinger H, Senn B, Hantikainen V, Köpke S, Ott S, Leino-Kilpi, H. Mobility care in nursing homes: Development and psychometric evaluation of the kinaesthetics competence self-evaluation (KCSE) scale. BMC Nursing. 2017;16(1):67.

4. Poole JL, New A, Garcia C. A comparison of performance on the Keitel Functional Test by persons with systemic sclerosis and rheumatoid arthritis. Disability and Rehabilitation. 2018;40(21): 2505-2508).

5. Brusilovskiy E, Klein LA, Salzer MS. Using global positioning systems to study health-related mobility and participation. Social Science & Medicine. 2016;161:134-142.

6. Axhausen, KW, Rai RK, Rieser M, Balmer M, Vaze VS. Capturing human activity spaces. ETH, Eidgenossische Technische Hochschule Zürich, IVT, Institut für Verkehrsplanung und Transportsysteme. http://dx.doi.org/10.3929/ethz-a005237115.

7. Rai RK, Balmer M, Rieser M, Vaze VS, Schönfelder S, Axhausen KW. Capturing human activity spaces: New geometries. Transportation Research Record. 2007;2021(1):70-80.

8. Brusilovskiy E, Klein L, Townley G, McCormick B, Snethen G, Salzer MS.. Community mental health center as a community participation affordance: Comparing visit days and non-visit days. Presented at APHA's 2019 Annual Meeting and Expo; November 2019; American Public Health Association.

9. Snethen G, Brusilovskiy E, Klein LA, McCormick B, Salzer MS. Community mobility and participation are associated with greater physical activity among individuals with schizophrenia-spectrum disorders. Presented at APHA's 2020 Annual Meeting and Expo; October 2020, American Public Health Association.

Biographies

Eugene Brusilovskiy is the Director of the Laboratory on Geography, Mobility and Disability at Temple University. He has served as co-investigator on numerous NIDRR-funded grants and has co-authored dozens of peer-reviewed manuscripts. His research interests include the use of innovative technologies and analytical tools to measure community mobility, community participation, and physical activity of individuals with disabilities, and examine how these variables are related to various health outcomes.

Mark Salzer, Ph.D. is a psychologist and Professor of Social and Behavioral Sciences in the College of Public Health at Temple University. He is also the Principal Investigator and Director of the Temple University Collaborative on Community Inclusion of Individuals with Psychiatric Disabilities, a rehabilitation research and training center funded by the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research since 2003. Dr. Salzer’s research focuses on community inclusion and participation.

Contact Information

Eugene Brusilovski

eugeneby@gmail.com

Mark Salzer

mark.salzer@temple.edu