Positive Approaches Journal, Volume 10, Issue 4

| Site: | My ODP |

| Course: | My ODP |

| Book: | Positive Approaches Journal, Volume 10, Issue 4 |

| Printed by: | |

| Date: | Sunday, February 8, 2026, 7:39 AM |

Positive Approaches Journal | 6

Volume 10 ► Issue 4 ► February 2022

Embracing Behavioral Supports and Meaningful Applications

Introduction

If there’s one thing we’ve learned in the past year, it’s the value of being able to pivot. Our routines have been ransacked, whether we’re providing support services in our jobs or planning a family gathering. Day by day, we evaluate the risks and benefits of any activity involving an encounter with others and make choices about social distance, masks, and using hand sanitizer. The restrictions have encouraged us to develop creative ways to take part in the world around us. Meeting in parks, virtual breakout rooms, or under patio lights by a firepit is now commonplace. Flexibility once praised primarily for people in creative endeavors, has become a survival strategy. And those who have mastered the ability to adapt quickly have thrived in spite of the obstacles.

Positive Behavioral Support, when done well, merges not only evidence-based practices but also ones that are flexible and creative. All humans use behaviors that work for them. Behavior specialists work like detectives uncovering clues and solving the puzzle to determine the functions of behavior. Each plan is unique and individualized, exploring not only observable consequences but also past trauma, environment, and genetics.

Articles in this issue

encourage us to focus on merging silos of mental and physical health and

incorporating biomedical and socio-environmental influences which all play into

how a person behaves. No longer limited to practices like discrete trial

training and aprons filled with M&M’s, Positive Behavioral Support has

proven effective in a variety of messy settings where challenging behaviors are

likely to be triggered, like fast-food restaurants, playgrounds, job sites, and

people’s homes. We’ve learned that behavioral approaches, once thought to be

effective only with specific populations of people with diagnoses like autism

or intellectual disability are effective for everyone, especially when

developing plans with people who require complex mental health support. Creating

multidisciplinary teams with a variety of stakeholders who like and admire the

person needing support helps to promote a positive outcome and ensures

simplicity and ease of administering a plan that works for everyone.

If this work inspires you, check out The Home and Community Positive Behavior Support (HCPBS) Network of the Association of Positive Behavior Support. HCPBS is a nonprofit organization that is dedicated to expanding and enhancing the application of positive behavior support principles across home and community settings, contexts, and the lifespan for people with behavioral challenges (including intellectual and developmental disabilities, mental health diagnoses, and seniors who require memory care and other related services) and the systems who support them. The HCPBS website (www.hcpbs.org) is loaded with practical resources, videos, stories of people who have been helped, and a treasure trove of evidence-based practices and research.

Molly

Dellinger-Wray, MS Ed

Home

and Community Positive Behavior Support Network

Partnership

for People with Disabilities at Virginia Commonwealth University

Positive Approaches Journal | 8-12

Volume 10 ► Issue 4 ► February 2022

Data Discoveries

The goal of Data Discoveries is to present useful data using new methods and platforms that can be customized.

Positive Behavioral

Supports (PBS) include a series of strategies for supporting individuals to

improve quality of life and decrease challenging behaviors through

evidence-based methods. PBS can be used in a variety of contexts like schools,

homes, and communities.1 While often described and implemented in

disability populations like those with developmental disabilities or autism

spectrum disorder (ASD)2,2 PBS has been used

in a wide array of populations including those with childhood obesity3 and an acquired

brain injury.4,5 One of the core principles of PBS is

the Assessment of Contexts and Functions.6 Assessment is

critical in PBS to track patterns in when, how, and within what context(s) a

behavior occurs to implement appropriate supports to improve individual quality

of life. Assessments can take many forms in PBS including “…record reviews,

interviews, and observations”.6 A Functional

Behavior Assessment (FBA) is one example of a process that can gather and

measure data surrounding a behavior that is occurring and identify variables

that may be impacting the cause and effect of the behavior.7 The goal of an

FBA as part of PBS is to assess and replace challenging behaviors.

Pennsylvania, through efforts of the Office of Developmental Programs (ODP), has

been propelling strategies to support providers, across the service system and

lifespan, in execution of FBAs as well as the development of a treatment or

behavior support plan that can be used across settings through an FBA training.

The ODP FBA training has been delivered in-person and via a DVD and has

recently been upgraded to be an interactive, self-paced module online format

that is widely accessible through the MyODP web platform.

The data dashboard below shows information about PBS and FBAs from several data sources. The first tab, ‘Positive Behavioral Supports in Publications’ shows the use of PBS in various populations that have been published in academic, peer-reviewed journals through a search of scholarly journal databases for the phrase “positive behavior supports”. Click on a circle and you will be directed to the full text of the PBS articles. The size of the circle represents the number of other research articles citing that article, which is sometimes referred to as the impact of the article (e.g, the bigger the circle, the more impact or the more others have cited the article). To learn more about implementation of FBA training and practice in in Pennsylvania, click on: ‘FBA Training in Pennsylvania Over Time’ to view a timeline of training in FBA delivered in Pennsylvania by ODP FBA training. You can also learn about ‘Provider Perceptions of FBAs’ to view responses to a 2017 survey conducted by ODP and the Autism Services, Education, Resources, & Training Collaborative (ASERT) to gather opinions and perspectives about the ODP FBA training content and process. Use the filters to view responses by provider type, role function, and ages of individuals supported.

Conclusion

For more resources and training to learn more about PBS, visit the Home and Community Positive Behavior Support Network (HCPBS) website (www.hcpbs.org/). HCBPS is a clearinghouse of resources, webinars, literature, and other information focused on the application of PBS in home and community-based settings. For more information about the web based ODP FBA training, visit: https://www.myodp.org/enrol/index.php?id=1644. For more resources about FBAs from ASERT visit: https://paautism.org/resource/functional-behavioral-assessment-student-education/.

References

1. Hieneman M. Positive Behavior Support for Individuals with Behavior Challenges. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2015;8(1):101-108. doi:10.1007/s40617-015-0051-6

2. Horner RH, Dunlap G, Koegel RL, et al. Toward a Technology of “Nonaversive” Behavioral Support. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities. 2005;30(1):3-10. doi:10.2511/rpsd.30.1.3

3. Smith JD, St. George SM, Prado G. Family-Centered Positive Behavior Support Interventions in Early Childhood To Prevent Obesity. Child Development. 2017;88(2):427-435. doi:10.1111/cdev.12738

4. Todd A, Horner HR, Vanater S, Schneider C. Working together to make change: An example of positive behavioral support for a student with traumatic brain injury. Education & treatment of children. 1997;20(4):425.

5. Gardner RM, Bird FL, Maguire H, Carreiro R, Abenaim N. Intensive Positive Behavior Supports for Adolescents with Acquired Brain Injury. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation. 2003;18(1):52-74. doi:10.1097/00001199-200301000-00007

6. What is Positive Behavior Support? Home and Community Positive Behavior Support Network (HCPBS). Accessed February 10, 2022. https://hcpbs.org/what-is-positive-behavior-support/

7. Shriver MD, Anderson CM, Proctor B. Evaluating

the Validity of Functional Behavior Assessment. School Psychology

Review. 2001;30(2):180-192. doi:10.1080/02796015.2001.12086108

Alford, Arva, Bell, Burger, Easley, Gaworski, Hollander & Treadway | 13-31

Volume 10 ► Issue 4 ► February 2022

Common Misconceptions About Behavioral Support – Debunked!

Amy Alford, M.Ed., BCBA; Heidi Arva; George Bell IV MA; Emily Burger, MS, NCC; Heather Easley; Lindsay Gaworski, M.Ed.; Jordan Hollander, M.Ed., BCBA, BSL; and Pamela Treadway, M.Ed.

Office of Developmental Programs Unified Clinical Team

Abstract

Behavioral support is often misunderstood, even while it provides a critical approach in supporting someone who may be using behaviors that interfere with optimal functioning and are challenging for supporters to understand. Applied research has provided the field with a plethora of evidence that this approach is an important consideration in treatment. The intent of this article is to provide accurate information about the behavioral approach as it applies to supporting people across the lifespan, who have varying disabilities, and work, live, and play in many settings and environments. The following misconceptions from the field will be reviewed:

- Misconception #1: Behavioral support only works for people with autism and certainly is not effective for people with mental illness.

- Misconception #2: Behavioral support is the only treatment modality that will address challenging or problematic behavior.

- Misconception #3: The more complex a person’s needs are, the more behavioral support is required.

- Misconception #4: Behavioral support is primarily focusing on developing rewards as reinforcement for the person to decrease their challenging or problematic behavior.

- Misconception #5: There is one right way to conduct a Functional Behavioral Assessment (FBA).

- Misconception #6: Behavioral support and therapy are the same.

Misconception #1: Behavioral support only works for people with autism and certainly is not effective for people with mental illness.

Research has established behavioral interventions as an effective treatment strategy for people with autism; however, that does not mean behavioral supports and interventions should be limited to those diagnosed with autism. Behavioral supports include the development and implementation of behavioral interventions that are grounded in FBA across diagnoses.

The connection between behavioral support and mental illness is often misunderstood and undervalued. Behavioral supports may be overlooked as a treatment option for people with mental illness because when we think of “behavior” we associate it with things that we can readily observe such as breaking objects, biting, or refusals to complete personal hygiene whereas mental illness is viewed as an internal or physiological state that we cannot easily observe. It is often misconstrued that there is nothing behavioral supports can do to address behavior that is attributed to an internal state. Griffiths, Gardner, and Nugent offer a comprehensive and individualized approach to functional behavioral assessment that incorporates assessment of both biomedical and socio-environmental influences.1 Biomedical factors may play a part in explaining the occurrence of problem behavior.

Behavioral assessment can effectively be utilized to understand the interaction between physiological (biomedical) and environmental factors. For example, an individual is diagnosed with an anxiety disorder and when faced with an anxiety-provoking

situation that results in physiological changes such as sweating and a pounding heart, a problem behavior such as physical aggression is triggered. An FBA can assist in identifying those situations that are associated with the physiological symptoms

of anxiety so that behavioral strategies can be put in place to prevent or reduce the likelihood of physical aggression. Additionally, the role of other biomedical factors such as medications, sleep, and medical conditions may be discovered during

the FBA which aids in the development of comprehensive behavioral interventions.

As the needs within our system grow so does the complexity of behavior. Factors like trauma, neurodevelopmental differences, environment, and genetics all play into how an individual behaves. It can create a confusing picture and many teams are not sure where to begin or what to address first. Utilizing a functional behavioral assessment can help to clarify that picture and to sort out the complexities. Mental health diagnoses are at their essence a collection of visible behaviors and internalized thoughts and emotions.2 It is not easy for the individual to sort out and verbalize nor is it easy for the outside observer. Practicing the use of purposeful, evidence-based tools allows the individual and the support team to better define and understand what is happening. Furthermore, it can potentially be determined what other factors influence the symptoms and can be changed or adapted to improve the outcome.3 There is evidence dating back to some of the very first behavior analysts that indicates that the modification of antecedents and triggers can produce different outcomes for those living with mental illness. In fact, behavior modification rooted in functional behavior assessment was used to support things like improvements in social skills, working skills, and overall independent living over 30 years ago.3

Misconception #2: Behavioral support is the only treatment modality that will address challenging or problematic behavior.

Effective behavioral supports require a multidisciplinary approach. This is especially true when the person receiving support has complex needs. Complex needs are complex because supports require a biopsychosocial approach – it’s never one thing. 3 As mentioned above, behavioral assessment can effectively be utilized to understand the interaction between physiological (biomedical) and environmental factors. Behaviors have a suspected physiological cause. It is within the scope of behavioral support to collaborate with other professionals to develop a holistic plan that includes recommendations and instructions from a multidisciplinary team, especially when the FBA does not demonstrate a clear relationship between environmental antecedent and behavioral function.

These professionals include:

- Psychiatrists for when the individual has a suspected or diagnosed condition that may require medication.

- Mental Health Professionals for when there is a suspected or diagnosed mental health condition that is outside the scope of practice for the behavioral specialist.

- Medical doctors for when there is a potential physiological cause that has been confirmed or one that has not been ruled out as a cause. A rule of thumb with a quality FBA is to rule out anything that may be medical first before developing behavioral-based strategies. This is especially important when the individual is experiencing pain, sleep issues, or food-related issues.

- Clinical Specialists such as substance abuse counselors, or sexuality specialists for when there are needs outside the behavioral specialist’s scope of competence.

Some of these professionals may already be involved when this person becomes known to the behavioral specialist and some may be identified during the FBA process when the behavioral specialists identify needs beyond their scope of practice and seek recommendations from relevant professionals. The resulting Behavioral Support Plan (BSP) should be a document that is consistent with and informed by the treatment plans developed by all members of the multidisciplinary team and is aligned with the individual’s values and goals.

Misconception #3: The more complex a person’s needs are, the more behavioral support is required.

One of the most common yet unfitting assumptions we encounter in supporting people with complex needs (i.e., needs requiring significant attention, resources, or supports) is that increases in maladaptive behavior should be met with an equivocal increase in service. In other words, the more concerning behavior a person exhibits, the more we attribute a need to increase direct behavioral supports. However, an increase in direct support is not always the answer. Of course, there are times where the challenges a person exhibits can be mitigated by increasing direct service, but often these increases can have an inverse effect, and can even exacerbate the problem. At its core, behavioral support is about the consistent implementation of the BSP by the entire support team.

As a review, let’s provide simple explanations for these two approaches.

- Direct Service: Direct implementation of strategies discussed in the BSP. These supports are often implemented by the behavior specialist, staff, family, or other caregivers and with the person themselves.

- Indirect Service: Analysis of fidelity of others implementing the plan through training, observation, data review, and feedback. Indirect services often occur without the person present, but always has the person as the focus.

In order to fully understand how to effectively support behaviors, we should first consider the philosophy of “quality over quantity.” Sometimes it is not necessarily how much direct support is provided, but rather the content, quality, and implementation of these services that truly drive effectiveness. Yet, the first response by many teams often involves some form of direct service increase. Instead of providing a quantitative response characterized by increases in direct support, emphasis should first consider a review of qualitative factors often found through indirect means. The focus should incorporate a review of plan fidelity and consistency of plan implementation. Additional indirect activities should incorporate a review of data, elicited feedback from the multidisciplinary team, observation, and additional training to supporters. It’s through these activities where most factors limiting success can be identified, resulting in a more profound impact than simply increasing direct support.

In summary, if response efforts maintain focus on indirect strategies that seek to analyze data and evaluate fidelity, changes can be made to better modify the environment and best meet the person’s individualized needs. When we question the effectiveness of supports, our focus is not always best served by increasing direct service with the individual. Instead, this provides an opportunity to enhance the implementation of indirect strategies that enable us to better understand the problem and how to best support the person. This includes an emphasis on:

- Plan Fidelity: Is the plan being implemented appropriately and consistently?

- Training: Do supporters require additional training to implement the plan more effectively and consistently?

- Data Analysis: What does the data tell us about the current situation?

- Plan

Modification: Does the data and additional analysis suggest a need to make changes to the current plan?

Adopting this approach empowers the multidisciplinary team to work collectively and ensure the application of supports is provided in a consistent manner, as they were intended, and helps to alter the practice of simply adding already ineffective direct supports as a means of better managing the person’s needs. Without these considerations, there is an increased risk of over-reliance on the behavioral specialist. After all, effective behavioral support is evidenced by empowering other members of the team to understand the function of challenging behaviors and implement individualized strategies with integrity.

Misconception #4: Behavioral support is primarily focusing on developing rewards as reinforcement for the person to decrease their challenging or problematic behavior.

When people think about behavioral support, many envision Pavlov’s dogs or Skinner’s reinforcement theory. Many think of sticker charts and token economies or tangible rewards used in discrete trials when training new skills. Though these are all components of its history, the field has grown from this simple notion of rewards and consequences to a rich tapestry of understanding and perspective rooted in the experience of the person supported.

A behavioral approach, at its core, is all about reinforcement, but the principles of reinforcement are often misunderstood. All humans engage in behavior that is functional to them. This means that our individual behavioral repertoires are developed throughout our lifetimes based on our experiences and responses to those experiences. We continue to engage in behaviors that have been successful in meeting our needs in different situations throughout our lives. Favorable consequences or outcomes make it more likely that the behavior that led to that outcome will occur in that situation in the future. This is the core of reinforcement theory, but behavioral support is so much more than a focus on decreasing challenging behavior by pairing new behaviors with rewards or privileges thought to be reinforcing.

Through the FBA process, a behavioral specialist should have a functional understanding of a person’s challenging behavior. This includes an understanding of the situations in which challenging behaviors have historically occurred as well as an understanding of WHY those situations may be challenging to the person. To understand the function is to understand the reinforcement history of that behavior. In practice, this means if the behavioral specialist has completed a quality FBA, they already know the needs of the person in specific challenging situations as well as what will likely reinforce more efficient alternative and replacement behaviors. Positive behavioral supports focus on modifying or avoiding those situations to help the person be more successful in the future. As one cannot simply suggest an environment change in isolation, one must couple that with skill-building, “...to promote performance of desired behaviors, support planners must ensure that these behaviors have been taught and that they produce adequate maintaining consequences (reinforcers) when they occur.4” This is accomplished in two ways. First teaching more efficiently achieves the same function when preventative strategies are not effective, and second, by teaching alternative behaviors that help the person cope with some of the challenges presented in those situations.

Behavior support in current practice takes a holistic approach to assessment and implementation. When a problem behavior has been identified and supports are sought, the gathering of information begins. As the assessment gives shape to the behavior support plan, we see the proactive nature of behavior support emerge. It is not about responding to a crisis and stopping the behavior at that moment but rather setting up the internal and external environment to respond proactively to avoid the crisis altogether. The plan focuses on identifying alternative, adaptive responses to a given trigger or antecedent and practicing those to create a fluidity that feels natural and then becomes the default.

Interventions focus on modeling, coaching, teaching, and transferring skills to the team and individual supported. This can only be accomplished through ongoing assessment and feedback of the efficacy of interventions and their outcomes. It

is not aversive conditioning but rather reteaching the response to triggers and antecedents and building the necessary skills to do so. Carr’s discussion suggests one can be confident that positive behavior support as an approach focuses on skill-building

and environmental design as the two vehicles for producing desirable change.5

If a person is only working for a reward when that reward is removed, the desired behavior will not likely continue. However, if you teach a person how to respond differently or adapt an environment to be more suitable, systematically fading and modifying

the reward contingencies as part of the larger plan, the conditions themselves work to change the behavior and lead to long-lasting success.

Misconception #5: There is one right way to conduct an FBA.

Behavioral support is rooted in FBA and therefore functional understanding of behavior. The FBA is not a one-time thing, but an ongoing process that should be the core of any BSP. Behavioral specialists should always base their interventions on the most current and comprehensive functional hypothesis of challenging behavior.

Unlike other assessments and tools, the FBA is an individualized process to understand why someone does what they do. By collecting information, analyzing information, and making data-based recommendations, a comprehensive BSP can be developed. If all FBAs are identical, you may be missing key information needed to understand the person you are supporting. Recognizing that an FBA is an ongoing process ensures that teams have the most up-to-date information and data to understand the function of the targeted behaviors. That being said, there are best practices to the FBA process that should be considered to ensure the BSP approaches treatment and intervention comprehensively, holistically, and individualized to the person.

The first best practice of the FBA process is through indirect and direct information gathering. Record reviews are one method of indirect information gathering which offers a historical perspective of the individual and the targeted behavior, while also gathering social, medical, educational, and/or behavioral information. There are no rules around what information must be gathered during record reviews, however, the information gathered should be relevant to the targeted behavior and understanding what may be maintaining the behaviors. Interviews are another form of indirect information gathering that offers personal perspectives from the individual and people who know them well. These personal perspectives can be gathered through questionnaires, rating tools, and/or structured/unstructured conversations. Some examples of these tools are the functional Assessment Interviews (FAI), Motivation Assessment Scale (MAS), Questions About Behavioral Function (QABF), and Functional Assessment Screening Tool (FAST). The questionnaires, tools or assessments that are used during the FBA process should provide enough information to formulate a hypothesis that will drive the multi-component behavioral support plan.

Direct information gathering includes observation of the individual in their natural environment. It should include data collection of the targeted behavior to more clearly define the behavior, support or refute the interview information, determine baseline levels and current levels of skills, provide objective information on conditions surrounding behaviors, and lead to a more accurate hypothesis of the behavior. The data collection method and items collected need to be specific to the individual. It should be succinct, targeted to the behavior of the individual, and written using clear, quantitative, consistent, and targeted language. Be sure to consider other elements of data collection beyond a frequency count (e.g. duration, latency, intensity).

Once the data is collected, a thorough analysis of the information to identify patterns, form hypothesis statements, and inform the data-based recommendations should be completed. Often, Excel or other similar programs are used to create graphs, but

there is great flexibility in how the information should be analyzed and presented to the person and other team members. The data-based recommendations should then be identified based upon the information gathered and analyzed as part of the FBA

process.

Many think this is the end of the FBA process, but this process should be ongoing for the duration of the time the person receives behavioral support. As support is provided and ongoing data is collected and analyzed, the behavioral hypothesis may

change and the strategies within the BSP must also change to reflect the most current hypothesis. The FBA must also be updated to reflect these changes.

Misconception #6: Behavioral support and therapy are the same.

The education and experience of a therapist or counselor provide an important perspective to behavioral support, but in practice it is very different from traditional therapy, counseling, or social work. Behavioral support is about more than the behavioral

specialist’s “sessions” with the individual. It is more than providing access to resources and tools. Behavioral support is more about DOING than THINKING. It uses data to assess problematic behaviors and creates a team implemented plan to teach

skills, express needs, and create more successful environments for the individual. Successful behavioral support relies primarily on the time outside the direct interaction with the behavioral specialist. Therapy, on the contrary, helps someone

develop strategies to change the way someone thinks. Primarily, a therapist works directly with the person to process feelings and emotions without direct intent to manipulate or change the environment and others in their environment.

Sometimes we feel like people need access to certain supports and when there are seemingly barriers to accessing needed supports, like counseling or therapy, the behavior specialist jumps in and takes on a role outside their scope. This well-intentioned act can be detrimental to the individual receiving services and can cross an ethical line that should not be crossed. Programs have different service lines for a reason. If someone needs therapy, they should receive therapy (in addition to behavioral support).

References

1. Gardner WI, Griffiths DM, Jo Anne Nugent, National Association For The Dually Diagnosed. Individual Centered Behavioral Interventions: A Multimodal Functional Approach. Nadd Press; 1998.

2. Wong SE. Behavior Analysis of Psychotic Disorders: Scientific Dead End or Casualty of the Mental Health Political Economy? Behavior and Social Issues. 2006;15(2):152-177. doi:10.5210/bsi.v15i2.365

3. Griffiths DM, Summers J, Chrissoula Stavrakaki. Dual Diagnosis: An Introduction to the Mental Health Needs of Persons with Developmental Disabilities. Habilitative Mental Health Resource Network; 2002.

4. Rehabilitation Research and Training Center on Positive Behavioral Support. PBS Practice. Association for Positive Behavioral Support. https://www.apbs.org/files/competingbehav_prac.pdf. Accessed January 5, 2022.

5. Carr EG, Dunlap G, Horner RH, et al. Positive Behavior Support: Evolution of an Applied Science. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions. January 2002; 4:4-16.

Biographies

Amy Alford M.Ed., BCBA, is a Senior Clinical Consultant for the Bureau of Supports for Autism and Special Populations (BSASP), Office of Developmental Programs (ODP). She has been supporting children, adolescents, and adults with autism and other developmental disabilities for over 15 years in community, home, and school settings. She holds a master’s degree in Special Education and in 2011, became a Board-Certified Behavior Analyst (BCBA). Prior to joining the BSASP clinical team in 2008, Amy was a behavioral specialist for a provider in the Behavioral Health Rehabilitation Services (BHRS) system (now Intensive Behavioral Health Services (IBHS)). She spends much of her time leading training efforts across ODP and continues to apply principles of positive behavioral supports and applied behavioral analysis throughout her work.

Heidi Arva has worked as a Clinical Consultant for ODP’s- Bureau of Supports for Autism and Special Populations since the Spring of 2016. Prior to working at ODP, she spent over 15 years providing direct support to adults, children, and families within the mental health system.

George Bell IV, MA is is currently assigned as the Regional Clinical Director for the Northeast Region's Office of Developmental Programs, Bureau of Community Services. He has worked with the state office for seven years. Prior to his current position, he worked with a private provider agency for more than twenty years supporting individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities in community-based programs.

Emily Burger MS, NCC is a Special Populations Professional in the Bureau of Supports for Autism and Special Populations. Prior to joining ODP, Emily worked with both the mental health and intellectual disability/autism community. She provided a wide variety of supports spanning from children's services, psychiatric rehabilitation, and residential community homes to most recently directing a behavioral support program. Currently she works with the Special Populations Unit focusing on complex cases with children, infant mental health and communication.

Heather Easley has worked for the Office of Developmental Programs (ODP)- Bureau of Supports for Autism and Special Populations as a Clinical consultant for 4 years. Prior to her work at ODP, Heather spent over 10 years supporting children, and adults across multiple systems.

Lindsay Gaworski joined ODP as a contractor in 2021 as a Clinical Director within the Western Region. Lindsay holds a Master of Education in Special Education from the University of Pittsburgh, with focused and intensive coursework in Applied Behavior Analysis. In addition, Lindsay has over 12 years of professional experience across multiple systems service lines including serving 2-5 year old children with ASD within a partial hospital setting, Intensive Behavioral Health Services (formerly BHRS) working with youth and families as a BSC while serving as a provider Autism Director, and most recently a Clinical leadership role within a residential provider. Lindsay is a graduate of the Capacity Building Institute, Year 3.

Jordan Hollander M.Ed.,

BCBA is a Senior Clinical Consultant for the Office of Developmental Programs – Bureau of Supports for Autism and Special Populations. He has been working for the past 12 years to help people on the autism spectrum identify goals, and work towards

achieving them through a person-centered approach that utilizes the principles of positive behavioral supports. Jordan has worked in various Direct Support Professional roles as well as in clinical and operational management positions for various

service providers throughout Southeastern PA.

Pamela Treadway, M.Ed., is a Senior Clinical Consultant for the Bureau of Supports for Autism Services and Special Populations, Office of Developmental Programs, Department of Human Services. She has been supporting individuals with disabilities for 42 years in home and community settings. She received a master's degree in special education from Lehigh University and has worked with adults and children with autism, intellectual disability, and emotional and behavioral disabilities.

Contact Information

Amy Alford M.Ed., BCBA

Office of Developmental Program – Bureau of Supports for Autism and Special Populations

Senior Clinical Consultant

Heidi Arva

Office of Developmental Program – Bureau of Supports for Autism and Special Populations

Clinical Consultant

c-harva@pa.gov

George Bell IV, MA

Office of Developmental Programs - Bureau of Community Supports

Clinical Director

Emily Burger MS, NCC

Office of Developmental Program – Bureau of Supports for Autism and Special Populations

Special Populations Professional

Heather Easley

Office of Developmental Program – Bureau of Supports for Autism and Special Populations

Clinical Consultant

Lindsay Gaworski

Office of Developmental Programs - Bureau of Community Supports

Clinical Director

Jordan Hollander M.Ed., BCBA

Office of Developmental Program – Bureau of Supports for Autism and Special Populations

Senior Clinical Consultant

Pamela Treadway

Office of Developmental Programs – Bureau of Supports for Autism and Special Populations

Senior Clinical Consultant

Hieneman & Fefer | 32-69

Volume 10 ► Issue 4 ► February 2022

Employing the Principles of Positive Behavior Support to Enhance Family Education and Intervention

Meme Hieneman & Sarah Fefer

I am

honored to share this article to memorialize my inspiring friend, mentor, and

colleague: Dr. Meme Hieneman. Meme lost her long and courageous battle with

cancer in August 2021. This is just one snapshot into Meme’s wide-ranging

contributions to the field of Positive Behavior Support (PBS), including

research and writing, teaching, mentoring, consulting, and advocacy work

focused on using this behavioral approach to enhance the family quality of

life. Her legacy includes many articles for Parenting Special Needs

magazine, creation of the Home and Community Positive Behavior Support Network,

development of the Practiced Routines curriculum, authoring two PBS

guides for families, leading numerous innovative and influential research

projects, and much more. I encourage you to continue to read and be inspired by

her work focused on applications of PBS in-home and community contexts.

In 2015, Meme and I co-presented at the annual conference of the Association of Positive Behavior Support to share our summary of the literature related to PBS in the context of family life. We shared models of effective family-focused intervention strategies from across disciplines and highlighted the PBS principles present in several existing evidence-based interventions for families. Our goal was to show how PBS was present in approaches that work to improve family lives. Sharing this work with fellow PBS professionals energized us to write this article to introduce the core principles of PBS to a broader range of researchers and practitioners focused on supporting individuals and families. We drew on examples of well-known family interventions to highlight their foundations in PBS principles and called for additional focus on the entire family context (rather than just on an individual or their caregivers) in future research and practice. I hope that this summary of core features of PBS will inspire others to think about how these features may be present, or how they can be enhanced, across a variety of prevention and intervention service delivery approaches in partnership with families.

Sarah A. Fefer, Ph.D. BCBA

Associate

Professor, School Psychology

University of Massachusetts Amherst

Abstract

Positive behavior

support (PBS) is an evidence-based approach for supporting adaptive behavior

and addressing behavioral challenges. It is critical that families have access

to effective evidence-based behavior support practices for both intervention

and prevention because they lead to better outcomes for families, and

counter-productive family management practices have been shown to further

escalate children’s behavioral challenges. PBS has been demonstrated to be

effective with individual children with serious behavior challenges in family

homes and features of PBS are evident in common family-based intervention

approaches. Unfortunately, complete application of PBS in family contexts has

not been fully explored or conceptualized.

The purpose of this paper is to define the core features of PBS

including lifestyle enhancement, assessment-based intervention, and

comprehensive support plans (i.e., including strategies for prevention,

teaching, and management). Examples of how the features of PBS are currently

being employed within the field of PBS and within other evidence-based parent

education and support programs are provided. Suggestions for how collaboration,

assessment, data-based decision making, comprehensive intervention, and tiered

approaches to service delivery may be used to enhance behavioral support for

families are offered. Lastly, future directions for research and practice are

recommended.

Introduction

Positive behavior support (PBS) is an evidence-based approach for supporting adaptive behavior and addressing behavioral challenges. It combines the principles of applied behavior analysis with approaches from other disciplines (e.g., ecological and community psychology, biomedical science, education) to improve the utility of behavioral intervention within typical home, school, and community environments.1,2,3,4 Although PBS was originally developed to overcome behavioral challenges of individuals with significant disabilities1, the approach has now been used successfully with a wider range of populations and applied within larger service systems (e.g., schools, mental health systems, early intervention programs, community agencies) to promote generalized behavioral improvements.5 Complete applications in family contexts, however, have been limited – even though the potential benefits are clear.

Families often experience significant stress related to child rearing, especially in dealing with children’s behavioral challenges.6,7,8 It is estimated that about 5% of children and youth experience challenging behavior9, with that figure increasing to 15% for children with disabilities.10,11 Siblings often display similar behavioral challenges12, making this a family problem. Significant behavior problems may delay children’s development, interfere with family routines, alienate children and families, and damage relationships.

When parents are knowledgeable and

skilled in effective behavioral support practices, they may use these practices

proactively, promoting family stability and creating environments in which

children thrive.13 When parents face behavioral challenges with

their children – an experience integral to family life - and do not possess the

necessary skills and knowledge to intervene effectively, they may be inclined

to resort to inconsistent, overly passive, or hostile approaches to managing

child behavior.14 Counter-productive family management practices

have been demonstrated to further escalate children’s behavioral challenges.15,16

Therefore, it is critical that parents have access to effective evidence-based

behavior support practices for both intervention and prevention.

PBS has been demonstrated to be effective with individual children with serious behavior challenges in family homes17and aspects of PBS are clearly evident in a variety of parent education programs.13, 18 It does not appear, however, that PBS has been comprehensively applied or assessed within family-based programs. In reviewing the literature, it is evident that some, but not all, features of PBS are incorporated in interventions focused on the child within the family or on the family system as a whole. In this article, we will define the core features of PBS, provide examples of how PBS is currently being employed within evidence-based parent education and support programs, and offer suggestions for how PBS may be used to enhance behavioral supports for families.

Features of Positive Behavior Support

PBS combines the technical foundations of applied behavior analysis with features derived from other fields to improve its practical utility within typical environments and routines. PBS is defined based on three core features: lifestyle enhancement, assessment-based intervention, and comprehensive support plans.1,19 Each of these features are described below with supporting literature.

Lifestyle enhancement

A foundational feature of applied behavior analysis is that the goals, interventions, and outcomes must be important and acceptable to the target individual or have “social validity”.20,21 In PBS, social validity has been interpreted as the extent to which interventions address and enhance quality of life, support teams are engaged in the process, and improvements are seen not only for individuals, but also throughout the systems that support them.

Quality of life

Quality of life refers to the extent to which an individual is satisfied and comfortable in their living circumstances.22 Quality of life is a complex multi-faceted concept that includes health and safety, self-advocacy, interpersonal relationships, productive activity, and community engagement. A critical element of life quality is self-determination – the degree to which people who are the focus of intervention efforts have a “voice and choice” in the process.23 The ultimate outcomes of PBS efforts are not only to develop skills and remediate behavior challenges, but to produce substantive improvements in lives of individuals, families, and other support and service providers.

Engagement of support teams

To ensure that PBS efforts are appropriate to the circumstances and ultimately successful, it is necessary to actively engage individuals and those who support them.24 Support teams commonly include family members, friends, neighbors, teachers, employers, therapists, social workers, and a host of other administrative and direct service professionals who may be influential in the success of PBS. The core members of these teams are included in goal identification, assessment, plan design, implementation, and evaluation.25

Support teams are engaged through planning processes that clarify desired outcomes and encompass action planning to work toward those outcomes. Various person-centered planning methods have been used within PBS.26 These planning processes guide support teams to establish a positive, unfettered vision for their future, assess available resources and potential barriers, and create a stepwise plan to work toward the goals. The limited research on the effectiveness of person-centered planning appears promising27 and its pragmatic value in PBS is evident.

Multi-tiered approach

PBS not only focuses on individuals, but also extends to the groups and systems that support them. PBS has been used extensively within schools, resulting in improvements in student attendance, academic performance, and behavior.28, 29 In addition, PBS is beginning to be employed within mental health and family support programs.30,31. These system-wide applications apply PBS principles within a multi-tiered framework in which effective behavior support practices are provided for everyone within the system proactively and universally, as well as more intensively and systematically for individuals who are at risk or experiencing significant behavioral challenges.

Assessment based intervention

Using objective data to inform and evaluate intervention is a cornerstone of PBS. It includes conducting assessments to inform strategy selection and tracking of both the integrity of implementation and outcomes of the intervention.

Assessing Contexts and Functions

PBS is grounded on the premise that effective behavioral support must be individualized based on the 1) needs of the focus individuals, 2) immediate and broader circumstances in which the individual function, and 3) consequences maintaining adaptive and maladaptive behavior patterns.32,33 It is therefore important to collect data to determine the purposes or functions behaviors are serving. Functions may include seeking attention from other people; acquiring tangible items such as food, money, games, or other desired objects; avoiding, delaying, or escaping unpleasant situations; or obtaining sensory outcomes such as increased stimulation or physical release. It is equally, if not more important, to identify the specific circumstances that set the stage for these functions.34 For example, individuals will most likely seek attention or items when deprived of them and will only endeavor to escape from situations that are uncomfortable or difficult.

Functional (and ecological) assessments in PBS involve systematically gathering information associated with the possible contexts and functions of behavior through interviews, record reviews, and observations.35,36 A variety of interview tools may be used from simple rating scales37,38,39 to more elaborate questionnaires.36 Direct observations are typically structured to obtain information on the antecedents, behaviors, and consequences40 or patterns of behavior across activities and time frames.41

Functional Behavior Assessments (FBAs) draw from multiple sources (e.g., interviewing multiple people, observing across settings and situations). Once sufficient data are collected, patterns of behavior are summarized in hypothesis statements. These statements describe the behaviors of concern, the circumstances in which they are most and least likely to occur, and the consequences that reliably follow the behavior (namely, their functions). For example, a hypothesis might be: “When Louis is asked to complete a difficult chore and not provided with frequent supervision, he will ‘get into stuff’ (e.g., take apart items or construct games). This delays completing the task and results in his parents increasing their guidance and attention.” These statements reflect the ‘best guess’ of the patterns but must be supported by data to be validated. That is done by either testing the hypotheses by manipulating events surrounding the behavior or implementing interventions based on them and evaluating their outcomes.42,43

Data-based decision making

Objective data are used to assess both the fidelity with which strategies are employed and the outcomes of intervention. These data guide decision-making and determine the need for adjustments to strategies and supports.44,45 For plans to be effective, they must be implemented as designed and with consistency. Therefore, a key feature of PBS intervention is to establish systems (e.g., checklists, periodic observations of strategy use) to ensure fidelity in practice.46 The data on behavior patterns may also offer insight into whether strategies are used successfully since variations in frequency/intensity can indicate that plans are not being used as intended under every circumstance.

Data are collected on behaviors that are most important and/or the best indicators of progress. These data may include discrete measures (e.g., frequency, duration) of particular behaviors that are a focus of intervention. The behaviors measured may include those targeted for increase such as appropriate communication (e.g., using words rather than physical aggression), independent participation in daily activities (e.g., household chores, work or school, self-care), or use of particular coping strategies. They may also include behaviors individuals need to decrease to be successful or safe including, for example, yelling at or threatening other people, stealing, or engaging in behavior that disrupts valued routines.

In addition to these more narrowly

defined behaviors, PBS also assesses quality of life outcomes as described

above).5 As a result of intervention, data should capture whether

people are able to go more places, do more things, and gain more enjoyment and

satisfaction from their daily lives.47

Since PBS is implemented in complex community settings (vs. segregated or controlled environments) and within natural routines, measures often need to be adapted to improve their ease of use for individuals and their caregivers. PBS practitioners therefore often supplement or replace the direct observation or continuous recording procedures commonly used in ABA with rating scales and sampling practices.44 By doing so, the rigor may be reduced, but contextual fit and fidelity of implementation are typically increased.

Comprehensive Intervention

Interventions in PBS are directly linked to the patterns identified in the assessment. They include immediate antecedent and consequence interventions, as well as broad lifestyle changes to support the more discrete strategies. A useful framework for selecting appropriate strategies is the competing behavior model.36Using this model, we identify interventions that are logically associated with particular patterns.

Components of PBS

PBS interventions are not stand-alone procedures, but include a combination of proactive, teaching, and management elements. These elements are described briefly in the following sections.

Proactive strategies include environmental and social arrangements that prompt positive behavior and make engagement in problem behavior unnecessary by modifying or removing the triggering stimuli.49 Examples of proactive strategies include: noncontingent access to attention, tangibles, and other reinforcers50; offering choices between items or activities51; activity scheduling to prepare for upcoming events52; and curricular modifications such as embedding easy or interesting features or reducing length or difficulty of tasks.53, 54

Teaching skills includes direct instruction in two types of competencies: (a) replacement behaviors and (b) other desired skills. Replacement behaviors are more appropriate responses that meet the same function as behaviors of concern. Functional communication training, for example, is a well-documented approach in which individuals are instructed to use words or other methods of expression to ask for items, attention, or breaks, depending on the purpose or function of the behavior.55, 56 More complex skills such as negotiation and problem-solving may also be taught as replacement behaviors. Other desired skills allow individuals to participate successfully in typical daily routines and meet the expectations of their circumstances. These may include social (e.g., engaging in conversations, playing games) and daily living (e.g., completing chores, homework, or other tasks) skills.57

Managing consequences involves maximizing reinforcement for positive behavior and reducing or eliminating reinforcement for problem behavior.58, 59, 60 To manage consequences effectively, the function of the behavior – access to attention or items/activities, escape, or sensory outcomes - must be clear and access to the specific reinforcers controlled. For example, consequences may involve delivering high rates of attention or reducing demands when individuals are cooperative, but not when they are complaining or aggressive.

Implementing PBS plans

Proactive, teaching, and management strategies are combined into comprehensive PBS plans that are tailored to the circumstances. These plans should be in writing and include goals and behaviors of concern, a summary of the patterns affecting behavior, descriptions of strategies and how they will be employed across situations, and methods for monitoring outcomes. For example, if a person’s behavior is motivated by attention from peers and the goal is to improve relationships, the plan might include creating opportunities for appropriate interactions (e.g., scheduling supervised gatherings, joining clubs, setting aside time for 1:1 interaction), teaching the individual any communication or social skills needed to obtain attention, and encouraging peers to respond to conversational turn taking instead of name-calling or threats. The individual could track the frequency of his or her interactions with other people and, together with peers, rate their quality.

In addition to these immediate strategies, other supports focused on setting events are often included as well. This means not only focusing on remediating behavioral challenges, but on creating universal, proactive measures to support positive behavior. Examples of these type of supports include restructuring routines or settings to better match people’s needs, rebuilding damaged relationships to improve the overall quality of interactions, addressing health or safety concerns that may be affecting behavior, or simply finding ways to offer more choice and personal autonomy.

As the PBS plan is being finalized, it is critical to consider its contextual fit given the people, settings, and systems that will be influenced by the plan.61 Questions to guide this consideration include: Is the plan right for the individual(s) for whom it is designed (i.e., given their characteristics, needs, abilities, preferences, and motivations)? Is the plan feasible given the resources available and doable within typical routines and settings? Do caregivers and others involved in supporting the plan have buy-in and the capacity to implement? Are broader systems (e.g., home, school, work, community) aligned with the plan and therefore likely to enhance sustainability62? Responses to these questions determine whether a plan needs to be adapted or whether accommodations may be needed.

Developing an action plan that addresses

the considerations above and spells out how each aspect of the plan will be put

in place is important to support implementation.44 The action plan

includes what exactly needs to be done, who will do it, and when it will be

completed. Action items typically include rearranging environments,

establishing routines, obtaining resources, providing training and coaching,

and establishing systems for monitoring implementation and outcomes and

communicating about progress. In addition, action planning often includes ways

to support and motivate plan implementers (e.g., via reminders, tools,

incentives).

A key to ensuring that PBS plans will be implemented

consistently and effectively is to embed strategies within typical daily

routines.63 Doing so reduces the demands on implementers and

increases sustainability as the strategies become part and parcel of routines

themselves. Examples of target routines may include tasks (e.g., chores,

homework, work responsibilities), personal care, play or leisure activities,

errands, and community outings. Effective instructional practices that are

inherent in the features of PBS may be used without disruption. These include

defining specific skills to teach; arranging settings to promote independence

and success; modeling, prompting, and shaping behavior; and using differential

reinforcement to establish and maintain skills over time.

EXAMPLES OF APPLICATION OF PBS FEATURES IN FAMILY INTERVENTION

Many well-established family education and support programs include features that are consistent with those that characterize PBS. In this section, we will highlight some examples, and demonstrate that, although comprehensive family-based PBS is not commonplace, current approaches do embrace these principles. The goal is not to provide an exhaustive review of all possible programs, but to share illustrations from the field of PBS and broader family intervention approaches.

Lifestyle Enhancement

Quality of life

Both researchers and practitioners have emphasized the importance of focusing on lifestyle enhancement when supporting behavior in family contexts. While few examples of direct quality of life measurement at the family level are available, Smith-Bird and Turnbull64 demonstrate that the intervention approaches and outcomes reported in past research on family focused PBS align with the key domains of the Beach Center Family Quality of Life Scale. Three themes related to quality of life were found in their analysis of past family PBS research: a focus on daily routines that are valued by families, improved family interaction, and increased safety/physical well-being for all family members.

Examples of routines that have been addressed in family-based PBS research include dinner, play, cleanup, bedtime, bathroom, or grocery shopping, or eating at a fast-food restaurant65, 66,67 also demonstrate ongoing direct measurement of individual quality of life through a community activity inventory. More comprehensive application and measurement of quality of life within family contexts in PBS is surprisingly limited.

Beyond literature in PBS, several evidence-based programs focus on empowering families to determine desired outcomes that will benefit their overall lifestyle. For example, the continuum of interventions offered within the Positive Parenting Program68 provides choices for families and promotes self-determination, while the Family Check-Up (FCU) program capitalizes on parent motivation by providing a menu of intervention options to families after an initial assessment and feedback session.69 Meta-analytic research suggests that involving parents in generating solutions is associated with higher ratings of satisfaction, self-efficacy, and social support.70

Comprehensive family intervention programs also directly measure outcomes associated with family quality of life. The Multidimensional Foster Care program71 measures quality of life through parent report, and targets other child and parent resiliency outcomes including interpersonal relationships, stability in home context, and social support.72 PPP has been shown to enhance parent and child well-being and parent relationship quality73, and FCU led to increased parental perceptions of social support and relationship satisfaction, decreased parenting stress, and fewer child challenging behaviors.74 The Incredible Years programs, which target increasing the family support network, have been shown to increase positive family communication and parental self-confidence, and reduce parental depression.18

Engagement of support teams

Given the focus on enhancing quality of life, it naturally follows that programs supporting families would endeavor to engage people across different systems and settings. This objective is explicit in wraparound76, 77 and group action planning77, both of which have been combined with PBS. The wraparound process, like PBS, involves a team of individuals working together to develop supports to enhance the life of individuals with disabilities across multiple important life domains.79 Group action planning expands on person-centered planning practices commonly used in PBS and is also directed by the preferences of an individual and their family.77 These approaches focus on coordinating supports by engaging all relevant family members and service providers in assessment, planning, and implementation to remediate challenges.

Coordinating multiple service providers is also common within other family-centered intervention programs beyond PBS, such as MTFC, in which weekly meetings are held with the family, clinicians, therapists, and skills coaches to review progress and engage in treatment planning.80 The FCU program also includes an “ecological management” option on the intervention menu for families who would benefit from coordination of the intervention with other child and family-focused community services.69 Family and support team involvement in intervention planning, and the measurement of outcomes associated with positive child and parent lifestyle change, are primary themes across a broad range of evidence-based family focused interventions.

Multi-tiered approach

Multi-tiered service delivery can be used within systems that provide support to multiple families to ensure that the level of service provided is aligned with the need demonstrated by the family. Several research teams have proposed the application of a multitier framework to enhance the efficiency of family-engagement practices in early childhood settings31, family support in urban family service agencies31, and parent training for young children with developmental disabilities.81 Tier 1 includes low intensity strategies available for all families such as reading materials about positive parenting strategies81, 82, parent workshops, or parent-teacher conferences Tier 2 involves more intensive group-based parent training or facilitated problem-solving sessions.31,80, 82, Tier 3 includes individualized supports for families with more persistent and intensive needs such as home-based sessions with video feedback80, structured reading or home-visit programs80, or direct training.31 The model empirically evaluated by Phaneuf and McIntyre82, but not frequently utilized in practice, is based on response to intervention logic, with all families starting with tier 1 supports.

PPP is a well-researched example of a multi-tiered model of family support.83 Triple P or PPP includes five levels or tiers starting with universal communication strategies such as posters or billboards, tv or radio commercials, or brochures. The aim of this level of support is to reach all families to share parenting strategies and de-stigmatize asking for help.84 The second level of support involves brief parent support during a routine pediatrician visits, followed by level 3 which includes repeat brief and specific consultation about child behavior. Level 4 is intensive group-based training in positive parenting skills, and level 5 is an individualized Enhanced Triple P program.84 This model of parent training is unique in that it acknowledges the unique needs of families, embeds family support within the broader societal context by implementing universal campaigns to put parenting on the public agenda, and draws upon existing services within the community.84 These aspects likely contribute to PPP being one of the most widely adopted models of parent training internationally.

The Incredible

Years programs also use multi-tier logic in acknowledging that children

present with various needs which may be targeted through varying levels of

direct intervention with children, teachers, or parents, or through more

comprehensive combined approaches.84 Within this conceptualization

of the tiered model less intensive supports are viewed as those that focus on

the child or parent alone, rather than intervening at the level of the family

system by working with both children and parents to reduce challenging

behavior. Webster-Stratton and Hammond85 demonstrated that working

with both children and parents (versus child

or parent-focused intervention) produced more positive and sustainable

outcomes; however, the authors acknowledged that this comprehensive approach

may not be needed by all families. The effectiveness of this more intensive

combined approach has also been demonstrated by Parent-Child Interaction Therapy.87

Assessment-Based Intervention

Assessment of contexts and functions

Collaboration between providers and families to complete functional assessments (e.g., interviews, observations, rating scales) and inform routine-based functional interventions is common within family-based PBS.88 Several research teams emphasize partnering with family members during this assessment process or supporting family members to carry out comprehensive functional assessment processes within family homes and during natural routines.89, 90, 91 This process often involves families identifying the most problematic routines for their child to serve as the context for the implementation of PBS, as well as the identification of prioritized target behaviors.65, 66, 92, 93, , Moes and Frea63 demonstrate that directly interviewing parents to gather information about the family context (e.g., routines, goals, supports, demands) can enhance the effectiveness of family-centered interventions such as Functional Communication Training.

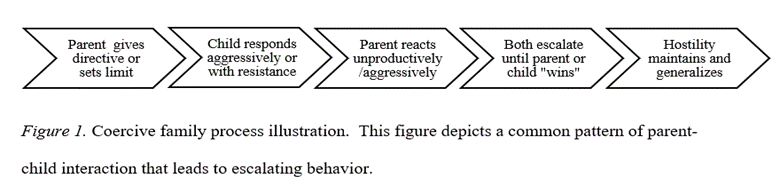

Preliminary work by Lucyshyn and colleagues94 also suggests that clinicians should directly assess parent-child interactions to determine patterns of reinforcement between parent and child that may escalate problem behavior. A possible reciprocal interaction between parent and child behavior is depicted in an illustration of the coercive family process in Figure 195 in which child behavior prompts unproductive parental responses, which thereby escalate child behavior. Using this perspective, the child’s behavior within the family context is of interest, along with the parent and child reactions that perpetuate those patterns and reinforce continuation of parental behavior.

This reciprocal or transactional relationship between parent and child behavior is the premise of many family-focused intervention programs that teach parents how to change their responses to their child’s behavior to prevent further escalation. PCIT96 involves direct observation of parents and children together, which informs the use of in-the-moment coaching for parents to improve their interactions and reduce coercive processes.97 The FCU program also includes observations of parents and children interacting in the home setting as part of a comprehensive assessment, which is used to inform a parent feedback session using motivational interviewing techniques to support parents in their choice of interventions from a menu of treatment options.69

Data-based decision making

The examples of family-based PBS research highlighted in the previous section incorporate multiple systems of data collection including structured observations and standard recording forms to look at the frequency, duration, and intensity of positive and challenging behaviors.66 These often include intensive direct observation and/or videotaping by the researchers themselves.

Although it would seem essential to engage families in monitoring progress (e.g., in order to capture data across situations throughout the day), there are fewer examples of direct parent involvement in this type of data collection for ongoing decision making.88,98, Few studies of family-focused PBS report treatment fidelity data, and those that do tend to use videotaped sessions to complete fidelity checklists rather than involving parents in monitoring their strategy use92, probably due to limitations in translating this type of intensive data collection from research to practice in family contexts. Lucyshyn and colleagues66, however, provide a comprehensive example of ongoing data-based decision making in partnership with families by including parent reports of problem behaviors as one source of information to monitor progress and make decisions to alter the intervention.

Family intervention programs beyond PBS provide

other examples of data-based decision making within the family context. PPP programs include tracking of the

fidelity of training components83 and methods to engage parents in

ongoing data-based decision making by teaching independent problem-solving

skills and providing tools and strategies to self-monitor the use of specific

skills taught.13 The most intensive individualized version of PPP, known as Enhanced Triple P, uses assessment data to guide individualization

of specific parent training modules based on family needs.83 PCIT87and Parent Management Training99

both use direct and indirect reports of interactions between children and

parents to guide the specific components of treatment and to evaluate progress.

PCIT uses data to inform the length

of the intervention; the intervention ends when parents master targeted

parenting skills and report that they are confident in managing child behavior.87

Comprehensive Interventions

In PBS, interventions are based on assessments and there is some degree of consistency in applying the framework that includes proactive and preventive strategies to address setting events and antecedents that precede behavioral patterns; teaching of desired and replacement skills; and reinforcement for positive, not problem, behavior in family contexts. Duda and colleagues65, for example, demonstrate that a combination of prevention, instruction, and reinforcement strategies reduced challenging behaviors across multiple home routines (e.g., play, cleanup, dinner). The strategies include social stories, providing choices, increasing proximity to the parent, pre-teaching rules, modeling and prompting appropriate play behaviors, teaching self-monitoring, a reward choice menu, and parent attention and praise. Lucyshyn et al.66 use similar prevent-teach-manage strategies, as well as information about family ecology to improve the contextual fit of the behavior support plan. Contextualized programs using family information (such as caregiving demands, family support needs, and social interactions goals) within comprehensive intervention programs are shown to be more effective at increasing replacement behaviors and decreasing challenging behaviors100 and lead to greater sustainability of communication skills.63

Pivotal Response Training101 also incorporates the three elements of comprehensive behavioral support, with an emphasis on teaching parents to use specific prevention (e.g., increasing child motivation through choice), teaching (e.g., modeling of new skills to encourage communication), and reinforcement (e.g., responding to all approximations of behavior with natural reinforcers) strategies within everyday activities and on an ongoing basis to increase skill development. These components are the basis for other intervention programs such as Prevent-Teach-Reinforce.102 Recent studies show that comprehensive intervention plans developed using the PTR model are effective to decrease challenging behavior and increase alternative behavior in young children and demonstrate that parents can effectively implement and generalize this intervention approach within family routines.103, 104 These PBS components have been integrated into other research as well. For example, Durand and colleagues17demonstrate the effectiveness of combining these core components of PBS with a cognitive behavioral therapy intervention to promote parental optimism.

Kazdin’s99 Parent Management Training is a forerunner in translating

behavioral principles into a comprehensive intervention approach for families.

Parents are taught specific behavioral strategies relevant to teaching and behavior

management such as praise, planned ignoring, time-out, and shaping within the

home context. Incredible Years, PCIT,

Triple P, and Multisystem Treatment

Foster Care follow suit and incorporate features of comprehensive behavior

support, as well as focus on preventing the coercive cycle. This is

accomplished in these programs by teaching parents’ prevention strategies

(e.g., increased praise and decreased criticism/commands, limit setting,

supervision/monitoring, relationship building), methods to model and prompt new

skills and positive behaviors, and specific reinforcement (e.g., structured

token economy system, increased attention to positive behavior and decreased

attention to negative behavior). A recent randomized clinical trial also

demonstrates the effectiveness of parent training that includes prevention,

teaching, and management strategies.105

Programs with Multiple PBS Components

Several books have

been written for professionals and parents specifically about parenting and

positive behavior support, combining these different features. They include

resources for professionals and parents. The first known resource related to

family PBS was Families and Positive

Behavior Support106, which included practical applications of

principles, case studies, and preliminary research in family contexts.

Hieneman, Childs, and Sergay107 made this information accessible for

parents in a self-guided problem-solving workbook that also offers suggestions

for universal supports. Durand and

Hieneman108 outlined a similar process for professionals working

with families entitled Positive Family

Intervention (that also includes cognitive-behavioral strategies to

overcome parental pessimism as a barrier to implementation). Durand109

wrote Optimistic Parenting to make these

approaches accessible to parents and added components of mindfulness and family

social support. Finally, as mentioned

earlier, Dunlap and colleagues102 have produced a Prevent-Teach-Reinforce for Families

manual written for practitioners working with families that outlines

comprehensive assessment and contextualized intervention approaches for home

and community settings.

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR PRACTICE

Over the years, ongoing research and field-based intervention with families has led to an increasing number of evidence-based clinical practices110. The way in which those practices are organized, selected, and delivered may be informed by both the principles of PBS and the growing body of literature on effective family support approaches. We offer the following recommendations based on this review:

Quality of life outcomes

Ensure that the goals of intervention are focused on quality-of-life improvements and fully embraced by the family – that they have social validity and contextual fit. Align goals with the families’ strengths, resources, needs, priorities, preferences, supports, and stressors. This means guiding, rather than directing, goal selection via processes of person and family-centered planning.

Family engagement

Engage all relevant family members and others whose involvement could influence the outcomes, valuing their input and rights as decision makers. Ensure their involvement in all aspects of the process of goal identification, assessment, plan design, implementation, and evaluation. Empower families to apply the principles (rather than just procedures) of PBS and become collaborative problem-solvers.

Comprehensive assessment

Conduct structured, comprehensive assessments to develop a valid understanding of immediate patterns and broader ecological variables affecting behavior within the family. Use the coercive family process95 framework to help families understand reciprocal interactions that may be maintaining problem behavior. Develop and utilize assessment tools36 to effectively and efficiently capture variables precipitating and maintaining behavior within families.

Support strategies and interventions