Positive Approaches Journal, Volume 10, Issue 4

Hieneman & Fefer | 32-69

Volume 10 ► Issue 4 ► February 2022

Employing the Principles of Positive Behavior Support to Enhance Family Education and Intervention

Meme Hieneman & Sarah Fefer

I am

honored to share this article to memorialize my inspiring friend, mentor, and

colleague: Dr. Meme Hieneman. Meme lost her long and courageous battle with

cancer in August 2021. This is just one snapshot into Meme’s wide-ranging

contributions to the field of Positive Behavior Support (PBS), including

research and writing, teaching, mentoring, consulting, and advocacy work

focused on using this behavioral approach to enhance the family quality of

life. Her legacy includes many articles for Parenting Special Needs

magazine, creation of the Home and Community Positive Behavior Support Network,

development of the Practiced Routines curriculum, authoring two PBS

guides for families, leading numerous innovative and influential research

projects, and much more. I encourage you to continue to read and be inspired by

her work focused on applications of PBS in-home and community contexts.

In 2015, Meme and I co-presented at the annual conference of the Association of Positive Behavior Support to share our summary of the literature related to PBS in the context of family life. We shared models of effective family-focused intervention strategies from across disciplines and highlighted the PBS principles present in several existing evidence-based interventions for families. Our goal was to show how PBS was present in approaches that work to improve family lives. Sharing this work with fellow PBS professionals energized us to write this article to introduce the core principles of PBS to a broader range of researchers and practitioners focused on supporting individuals and families. We drew on examples of well-known family interventions to highlight their foundations in PBS principles and called for additional focus on the entire family context (rather than just on an individual or their caregivers) in future research and practice. I hope that this summary of core features of PBS will inspire others to think about how these features may be present, or how they can be enhanced, across a variety of prevention and intervention service delivery approaches in partnership with families.

Sarah A. Fefer, Ph.D. BCBA

Associate

Professor, School Psychology

University of Massachusetts Amherst

Abstract

Positive behavior

support (PBS) is an evidence-based approach for supporting adaptive behavior

and addressing behavioral challenges. It is critical that families have access

to effective evidence-based behavior support practices for both intervention

and prevention because they lead to better outcomes for families, and

counter-productive family management practices have been shown to further

escalate children’s behavioral challenges. PBS has been demonstrated to be

effective with individual children with serious behavior challenges in family

homes and features of PBS are evident in common family-based intervention

approaches. Unfortunately, complete application of PBS in family contexts has

not been fully explored or conceptualized.

The purpose of this paper is to define the core features of PBS

including lifestyle enhancement, assessment-based intervention, and

comprehensive support plans (i.e., including strategies for prevention,

teaching, and management). Examples of how the features of PBS are currently

being employed within the field of PBS and within other evidence-based parent

education and support programs are provided. Suggestions for how collaboration,

assessment, data-based decision making, comprehensive intervention, and tiered

approaches to service delivery may be used to enhance behavioral support for

families are offered. Lastly, future directions for research and practice are

recommended.

Introduction

Positive behavior support (PBS) is an evidence-based approach for supporting adaptive behavior and addressing behavioral challenges. It combines the principles of applied behavior analysis with approaches from other disciplines (e.g., ecological and community psychology, biomedical science, education) to improve the utility of behavioral intervention within typical home, school, and community environments.1,2,3,4 Although PBS was originally developed to overcome behavioral challenges of individuals with significant disabilities1, the approach has now been used successfully with a wider range of populations and applied within larger service systems (e.g., schools, mental health systems, early intervention programs, community agencies) to promote generalized behavioral improvements.5 Complete applications in family contexts, however, have been limited – even though the potential benefits are clear.

Families often experience significant stress related to child rearing, especially in dealing with children’s behavioral challenges.6,7,8 It is estimated that about 5% of children and youth experience challenging behavior9, with that figure increasing to 15% for children with disabilities.10,11 Siblings often display similar behavioral challenges12, making this a family problem. Significant behavior problems may delay children’s development, interfere with family routines, alienate children and families, and damage relationships.

When parents are knowledgeable and

skilled in effective behavioral support practices, they may use these practices

proactively, promoting family stability and creating environments in which

children thrive.13 When parents face behavioral challenges with

their children – an experience integral to family life - and do not possess the

necessary skills and knowledge to intervene effectively, they may be inclined

to resort to inconsistent, overly passive, or hostile approaches to managing

child behavior.14 Counter-productive family management practices

have been demonstrated to further escalate children’s behavioral challenges.15,16

Therefore, it is critical that parents have access to effective evidence-based

behavior support practices for both intervention and prevention.

PBS has been demonstrated to be effective with individual children with serious behavior challenges in family homes17and aspects of PBS are clearly evident in a variety of parent education programs.13, 18 It does not appear, however, that PBS has been comprehensively applied or assessed within family-based programs. In reviewing the literature, it is evident that some, but not all, features of PBS are incorporated in interventions focused on the child within the family or on the family system as a whole. In this article, we will define the core features of PBS, provide examples of how PBS is currently being employed within evidence-based parent education and support programs, and offer suggestions for how PBS may be used to enhance behavioral supports for families.

Features of Positive Behavior Support

PBS combines the technical foundations of applied behavior analysis with features derived from other fields to improve its practical utility within typical environments and routines. PBS is defined based on three core features: lifestyle enhancement, assessment-based intervention, and comprehensive support plans.1,19 Each of these features are described below with supporting literature.

Lifestyle enhancement

A foundational feature of applied behavior analysis is that the goals, interventions, and outcomes must be important and acceptable to the target individual or have “social validity”.20,21 In PBS, social validity has been interpreted as the extent to which interventions address and enhance quality of life, support teams are engaged in the process, and improvements are seen not only for individuals, but also throughout the systems that support them.

Quality of life

Quality of life refers to the extent to which an individual is satisfied and comfortable in their living circumstances.22 Quality of life is a complex multi-faceted concept that includes health and safety, self-advocacy, interpersonal relationships, productive activity, and community engagement. A critical element of life quality is self-determination – the degree to which people who are the focus of intervention efforts have a “voice and choice” in the process.23 The ultimate outcomes of PBS efforts are not only to develop skills and remediate behavior challenges, but to produce substantive improvements in lives of individuals, families, and other support and service providers.

Engagement of support teams

To ensure that PBS efforts are appropriate to the circumstances and ultimately successful, it is necessary to actively engage individuals and those who support them.24 Support teams commonly include family members, friends, neighbors, teachers, employers, therapists, social workers, and a host of other administrative and direct service professionals who may be influential in the success of PBS. The core members of these teams are included in goal identification, assessment, plan design, implementation, and evaluation.25

Support teams are engaged through planning processes that clarify desired outcomes and encompass action planning to work toward those outcomes. Various person-centered planning methods have been used within PBS.26 These planning processes guide support teams to establish a positive, unfettered vision for their future, assess available resources and potential barriers, and create a stepwise plan to work toward the goals. The limited research on the effectiveness of person-centered planning appears promising27 and its pragmatic value in PBS is evident.

Multi-tiered approach

PBS not only focuses on individuals, but also extends to the groups and systems that support them. PBS has been used extensively within schools, resulting in improvements in student attendance, academic performance, and behavior.28, 29 In addition, PBS is beginning to be employed within mental health and family support programs.30,31. These system-wide applications apply PBS principles within a multi-tiered framework in which effective behavior support practices are provided for everyone within the system proactively and universally, as well as more intensively and systematically for individuals who are at risk or experiencing significant behavioral challenges.

Assessment based intervention

Using objective data to inform and evaluate intervention is a cornerstone of PBS. It includes conducting assessments to inform strategy selection and tracking of both the integrity of implementation and outcomes of the intervention.

Assessing Contexts and Functions

PBS is grounded on the premise that effective behavioral support must be individualized based on the 1) needs of the focus individuals, 2) immediate and broader circumstances in which the individual function, and 3) consequences maintaining adaptive and maladaptive behavior patterns.32,33 It is therefore important to collect data to determine the purposes or functions behaviors are serving. Functions may include seeking attention from other people; acquiring tangible items such as food, money, games, or other desired objects; avoiding, delaying, or escaping unpleasant situations; or obtaining sensory outcomes such as increased stimulation or physical release. It is equally, if not more important, to identify the specific circumstances that set the stage for these functions.34 For example, individuals will most likely seek attention or items when deprived of them and will only endeavor to escape from situations that are uncomfortable or difficult.

Functional (and ecological) assessments in PBS involve systematically gathering information associated with the possible contexts and functions of behavior through interviews, record reviews, and observations.35,36 A variety of interview tools may be used from simple rating scales37,38,39 to more elaborate questionnaires.36 Direct observations are typically structured to obtain information on the antecedents, behaviors, and consequences40 or patterns of behavior across activities and time frames.41

Functional Behavior Assessments (FBAs) draw from multiple sources (e.g., interviewing multiple people, observing across settings and situations). Once sufficient data are collected, patterns of behavior are summarized in hypothesis statements. These statements describe the behaviors of concern, the circumstances in which they are most and least likely to occur, and the consequences that reliably follow the behavior (namely, their functions). For example, a hypothesis might be: “When Louis is asked to complete a difficult chore and not provided with frequent supervision, he will ‘get into stuff’ (e.g., take apart items or construct games). This delays completing the task and results in his parents increasing their guidance and attention.” These statements reflect the ‘best guess’ of the patterns but must be supported by data to be validated. That is done by either testing the hypotheses by manipulating events surrounding the behavior or implementing interventions based on them and evaluating their outcomes.42,43

Data-based decision making

Objective data are used to assess both the fidelity with which strategies are employed and the outcomes of intervention. These data guide decision-making and determine the need for adjustments to strategies and supports.44,45 For plans to be effective, they must be implemented as designed and with consistency. Therefore, a key feature of PBS intervention is to establish systems (e.g., checklists, periodic observations of strategy use) to ensure fidelity in practice.46 The data on behavior patterns may also offer insight into whether strategies are used successfully since variations in frequency/intensity can indicate that plans are not being used as intended under every circumstance.

Data are collected on behaviors that are most important and/or the best indicators of progress. These data may include discrete measures (e.g., frequency, duration) of particular behaviors that are a focus of intervention. The behaviors measured may include those targeted for increase such as appropriate communication (e.g., using words rather than physical aggression), independent participation in daily activities (e.g., household chores, work or school, self-care), or use of particular coping strategies. They may also include behaviors individuals need to decrease to be successful or safe including, for example, yelling at or threatening other people, stealing, or engaging in behavior that disrupts valued routines.

In addition to these more narrowly

defined behaviors, PBS also assesses quality of life outcomes as described

above).5 As a result of intervention, data should capture whether

people are able to go more places, do more things, and gain more enjoyment and

satisfaction from their daily lives.47

Since PBS is implemented in complex community settings (vs. segregated or controlled environments) and within natural routines, measures often need to be adapted to improve their ease of use for individuals and their caregivers. PBS practitioners therefore often supplement or replace the direct observation or continuous recording procedures commonly used in ABA with rating scales and sampling practices.44 By doing so, the rigor may be reduced, but contextual fit and fidelity of implementation are typically increased.

Comprehensive Intervention

Interventions in PBS are directly linked to the patterns identified in the assessment. They include immediate antecedent and consequence interventions, as well as broad lifestyle changes to support the more discrete strategies. A useful framework for selecting appropriate strategies is the competing behavior model.36Using this model, we identify interventions that are logically associated with particular patterns.

Components of PBS

PBS interventions are not stand-alone procedures, but include a combination of proactive, teaching, and management elements. These elements are described briefly in the following sections.

Proactive strategies include environmental and social arrangements that prompt positive behavior and make engagement in problem behavior unnecessary by modifying or removing the triggering stimuli.49 Examples of proactive strategies include: noncontingent access to attention, tangibles, and other reinforcers50; offering choices between items or activities51; activity scheduling to prepare for upcoming events52; and curricular modifications such as embedding easy or interesting features or reducing length or difficulty of tasks.53, 54

Teaching skills includes direct instruction in two types of competencies: (a) replacement behaviors and (b) other desired skills. Replacement behaviors are more appropriate responses that meet the same function as behaviors of concern. Functional communication training, for example, is a well-documented approach in which individuals are instructed to use words or other methods of expression to ask for items, attention, or breaks, depending on the purpose or function of the behavior.55, 56 More complex skills such as negotiation and problem-solving may also be taught as replacement behaviors. Other desired skills allow individuals to participate successfully in typical daily routines and meet the expectations of their circumstances. These may include social (e.g., engaging in conversations, playing games) and daily living (e.g., completing chores, homework, or other tasks) skills.57

Managing consequences involves maximizing reinforcement for positive behavior and reducing or eliminating reinforcement for problem behavior.58, 59, 60 To manage consequences effectively, the function of the behavior – access to attention or items/activities, escape, or sensory outcomes - must be clear and access to the specific reinforcers controlled. For example, consequences may involve delivering high rates of attention or reducing demands when individuals are cooperative, but not when they are complaining or aggressive.

Implementing PBS plans

Proactive, teaching, and management strategies are combined into comprehensive PBS plans that are tailored to the circumstances. These plans should be in writing and include goals and behaviors of concern, a summary of the patterns affecting behavior, descriptions of strategies and how they will be employed across situations, and methods for monitoring outcomes. For example, if a person’s behavior is motivated by attention from peers and the goal is to improve relationships, the plan might include creating opportunities for appropriate interactions (e.g., scheduling supervised gatherings, joining clubs, setting aside time for 1:1 interaction), teaching the individual any communication or social skills needed to obtain attention, and encouraging peers to respond to conversational turn taking instead of name-calling or threats. The individual could track the frequency of his or her interactions with other people and, together with peers, rate their quality.

In addition to these immediate strategies, other supports focused on setting events are often included as well. This means not only focusing on remediating behavioral challenges, but on creating universal, proactive measures to support positive behavior. Examples of these type of supports include restructuring routines or settings to better match people’s needs, rebuilding damaged relationships to improve the overall quality of interactions, addressing health or safety concerns that may be affecting behavior, or simply finding ways to offer more choice and personal autonomy.

As the PBS plan is being finalized, it is critical to consider its contextual fit given the people, settings, and systems that will be influenced by the plan.61 Questions to guide this consideration include: Is the plan right for the individual(s) for whom it is designed (i.e., given their characteristics, needs, abilities, preferences, and motivations)? Is the plan feasible given the resources available and doable within typical routines and settings? Do caregivers and others involved in supporting the plan have buy-in and the capacity to implement? Are broader systems (e.g., home, school, work, community) aligned with the plan and therefore likely to enhance sustainability62? Responses to these questions determine whether a plan needs to be adapted or whether accommodations may be needed.

Developing an action plan that addresses

the considerations above and spells out how each aspect of the plan will be put

in place is important to support implementation.44 The action plan

includes what exactly needs to be done, who will do it, and when it will be

completed. Action items typically include rearranging environments,

establishing routines, obtaining resources, providing training and coaching,

and establishing systems for monitoring implementation and outcomes and

communicating about progress. In addition, action planning often includes ways

to support and motivate plan implementers (e.g., via reminders, tools,

incentives).

A key to ensuring that PBS plans will be implemented

consistently and effectively is to embed strategies within typical daily

routines.63 Doing so reduces the demands on implementers and

increases sustainability as the strategies become part and parcel of routines

themselves. Examples of target routines may include tasks (e.g., chores,

homework, work responsibilities), personal care, play or leisure activities,

errands, and community outings. Effective instructional practices that are

inherent in the features of PBS may be used without disruption. These include

defining specific skills to teach; arranging settings to promote independence

and success; modeling, prompting, and shaping behavior; and using differential

reinforcement to establish and maintain skills over time.

EXAMPLES OF APPLICATION OF PBS FEATURES IN FAMILY INTERVENTION

Many well-established family education and support programs include features that are consistent with those that characterize PBS. In this section, we will highlight some examples, and demonstrate that, although comprehensive family-based PBS is not commonplace, current approaches do embrace these principles. The goal is not to provide an exhaustive review of all possible programs, but to share illustrations from the field of PBS and broader family intervention approaches.

Lifestyle Enhancement

Quality of life

Both researchers and practitioners have emphasized the importance of focusing on lifestyle enhancement when supporting behavior in family contexts. While few examples of direct quality of life measurement at the family level are available, Smith-Bird and Turnbull64 demonstrate that the intervention approaches and outcomes reported in past research on family focused PBS align with the key domains of the Beach Center Family Quality of Life Scale. Three themes related to quality of life were found in their analysis of past family PBS research: a focus on daily routines that are valued by families, improved family interaction, and increased safety/physical well-being for all family members.

Examples of routines that have been addressed in family-based PBS research include dinner, play, cleanup, bedtime, bathroom, or grocery shopping, or eating at a fast-food restaurant65, 66,67 also demonstrate ongoing direct measurement of individual quality of life through a community activity inventory. More comprehensive application and measurement of quality of life within family contexts in PBS is surprisingly limited.

Beyond literature in PBS, several evidence-based programs focus on empowering families to determine desired outcomes that will benefit their overall lifestyle. For example, the continuum of interventions offered within the Positive Parenting Program68 provides choices for families and promotes self-determination, while the Family Check-Up (FCU) program capitalizes on parent motivation by providing a menu of intervention options to families after an initial assessment and feedback session.69 Meta-analytic research suggests that involving parents in generating solutions is associated with higher ratings of satisfaction, self-efficacy, and social support.70

Comprehensive family intervention programs also directly measure outcomes associated with family quality of life. The Multidimensional Foster Care program71 measures quality of life through parent report, and targets other child and parent resiliency outcomes including interpersonal relationships, stability in home context, and social support.72 PPP has been shown to enhance parent and child well-being and parent relationship quality73, and FCU led to increased parental perceptions of social support and relationship satisfaction, decreased parenting stress, and fewer child challenging behaviors.74 The Incredible Years programs, which target increasing the family support network, have been shown to increase positive family communication and parental self-confidence, and reduce parental depression.18

Engagement of support teams

Given the focus on enhancing quality of life, it naturally follows that programs supporting families would endeavor to engage people across different systems and settings. This objective is explicit in wraparound76, 77 and group action planning77, both of which have been combined with PBS. The wraparound process, like PBS, involves a team of individuals working together to develop supports to enhance the life of individuals with disabilities across multiple important life domains.79 Group action planning expands on person-centered planning practices commonly used in PBS and is also directed by the preferences of an individual and their family.77 These approaches focus on coordinating supports by engaging all relevant family members and service providers in assessment, planning, and implementation to remediate challenges.

Coordinating multiple service providers is also common within other family-centered intervention programs beyond PBS, such as MTFC, in which weekly meetings are held with the family, clinicians, therapists, and skills coaches to review progress and engage in treatment planning.80 The FCU program also includes an “ecological management” option on the intervention menu for families who would benefit from coordination of the intervention with other child and family-focused community services.69 Family and support team involvement in intervention planning, and the measurement of outcomes associated with positive child and parent lifestyle change, are primary themes across a broad range of evidence-based family focused interventions.

Multi-tiered approach

Multi-tiered service delivery can be used within systems that provide support to multiple families to ensure that the level of service provided is aligned with the need demonstrated by the family. Several research teams have proposed the application of a multitier framework to enhance the efficiency of family-engagement practices in early childhood settings31, family support in urban family service agencies31, and parent training for young children with developmental disabilities.81 Tier 1 includes low intensity strategies available for all families such as reading materials about positive parenting strategies81, 82, parent workshops, or parent-teacher conferences Tier 2 involves more intensive group-based parent training or facilitated problem-solving sessions.31,80, 82, Tier 3 includes individualized supports for families with more persistent and intensive needs such as home-based sessions with video feedback80, structured reading or home-visit programs80, or direct training.31 The model empirically evaluated by Phaneuf and McIntyre82, but not frequently utilized in practice, is based on response to intervention logic, with all families starting with tier 1 supports.

PPP is a well-researched example of a multi-tiered model of family support.83 Triple P or PPP includes five levels or tiers starting with universal communication strategies such as posters or billboards, tv or radio commercials, or brochures. The aim of this level of support is to reach all families to share parenting strategies and de-stigmatize asking for help.84 The second level of support involves brief parent support during a routine pediatrician visits, followed by level 3 which includes repeat brief and specific consultation about child behavior. Level 4 is intensive group-based training in positive parenting skills, and level 5 is an individualized Enhanced Triple P program.84 This model of parent training is unique in that it acknowledges the unique needs of families, embeds family support within the broader societal context by implementing universal campaigns to put parenting on the public agenda, and draws upon existing services within the community.84 These aspects likely contribute to PPP being one of the most widely adopted models of parent training internationally.

The Incredible

Years programs also use multi-tier logic in acknowledging that children

present with various needs which may be targeted through varying levels of

direct intervention with children, teachers, or parents, or through more

comprehensive combined approaches.84 Within this conceptualization

of the tiered model less intensive supports are viewed as those that focus on

the child or parent alone, rather than intervening at the level of the family

system by working with both children and parents to reduce challenging

behavior. Webster-Stratton and Hammond85 demonstrated that working

with both children and parents (versus child

or parent-focused intervention) produced more positive and sustainable

outcomes; however, the authors acknowledged that this comprehensive approach

may not be needed by all families. The effectiveness of this more intensive

combined approach has also been demonstrated by Parent-Child Interaction Therapy.87

Assessment-Based Intervention

Assessment of contexts and functions

Collaboration between providers and families to complete functional assessments (e.g., interviews, observations, rating scales) and inform routine-based functional interventions is common within family-based PBS.88 Several research teams emphasize partnering with family members during this assessment process or supporting family members to carry out comprehensive functional assessment processes within family homes and during natural routines.89, 90, 91 This process often involves families identifying the most problematic routines for their child to serve as the context for the implementation of PBS, as well as the identification of prioritized target behaviors.65, 66, 92, 93, , Moes and Frea63 demonstrate that directly interviewing parents to gather information about the family context (e.g., routines, goals, supports, demands) can enhance the effectiveness of family-centered interventions such as Functional Communication Training.

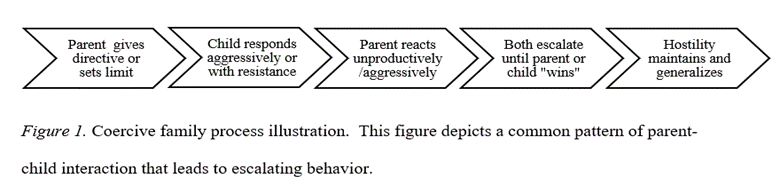

Preliminary work by Lucyshyn and colleagues94 also suggests that clinicians should directly assess parent-child interactions to determine patterns of reinforcement between parent and child that may escalate problem behavior. A possible reciprocal interaction between parent and child behavior is depicted in an illustration of the coercive family process in Figure 195 in which child behavior prompts unproductive parental responses, which thereby escalate child behavior. Using this perspective, the child’s behavior within the family context is of interest, along with the parent and child reactions that perpetuate those patterns and reinforce continuation of parental behavior.

This reciprocal or transactional relationship between parent and child behavior is the premise of many family-focused intervention programs that teach parents how to change their responses to their child’s behavior to prevent further escalation. PCIT96 involves direct observation of parents and children together, which informs the use of in-the-moment coaching for parents to improve their interactions and reduce coercive processes.97 The FCU program also includes observations of parents and children interacting in the home setting as part of a comprehensive assessment, which is used to inform a parent feedback session using motivational interviewing techniques to support parents in their choice of interventions from a menu of treatment options.69

Data-based decision making

The examples of family-based PBS research highlighted in the previous section incorporate multiple systems of data collection including structured observations and standard recording forms to look at the frequency, duration, and intensity of positive and challenging behaviors.66 These often include intensive direct observation and/or videotaping by the researchers themselves.

Although it would seem essential to engage families in monitoring progress (e.g., in order to capture data across situations throughout the day), there are fewer examples of direct parent involvement in this type of data collection for ongoing decision making.88,98, Few studies of family-focused PBS report treatment fidelity data, and those that do tend to use videotaped sessions to complete fidelity checklists rather than involving parents in monitoring their strategy use92, probably due to limitations in translating this type of intensive data collection from research to practice in family contexts. Lucyshyn and colleagues66, however, provide a comprehensive example of ongoing data-based decision making in partnership with families by including parent reports of problem behaviors as one source of information to monitor progress and make decisions to alter the intervention.

Family intervention programs beyond PBS provide

other examples of data-based decision making within the family context. PPP programs include tracking of the

fidelity of training components83 and methods to engage parents in

ongoing data-based decision making by teaching independent problem-solving

skills and providing tools and strategies to self-monitor the use of specific

skills taught.13 The most intensive individualized version of PPP, known as Enhanced Triple P, uses assessment data to guide individualization

of specific parent training modules based on family needs.83 PCIT87and Parent Management Training99

both use direct and indirect reports of interactions between children and

parents to guide the specific components of treatment and to evaluate progress.

PCIT uses data to inform the length

of the intervention; the intervention ends when parents master targeted

parenting skills and report that they are confident in managing child behavior.87

Comprehensive Interventions

In PBS, interventions are based on assessments and there is some degree of consistency in applying the framework that includes proactive and preventive strategies to address setting events and antecedents that precede behavioral patterns; teaching of desired and replacement skills; and reinforcement for positive, not problem, behavior in family contexts. Duda and colleagues65, for example, demonstrate that a combination of prevention, instruction, and reinforcement strategies reduced challenging behaviors across multiple home routines (e.g., play, cleanup, dinner). The strategies include social stories, providing choices, increasing proximity to the parent, pre-teaching rules, modeling and prompting appropriate play behaviors, teaching self-monitoring, a reward choice menu, and parent attention and praise. Lucyshyn et al.66 use similar prevent-teach-manage strategies, as well as information about family ecology to improve the contextual fit of the behavior support plan. Contextualized programs using family information (such as caregiving demands, family support needs, and social interactions goals) within comprehensive intervention programs are shown to be more effective at increasing replacement behaviors and decreasing challenging behaviors100 and lead to greater sustainability of communication skills.63

Pivotal Response Training101 also incorporates the three elements of comprehensive behavioral support, with an emphasis on teaching parents to use specific prevention (e.g., increasing child motivation through choice), teaching (e.g., modeling of new skills to encourage communication), and reinforcement (e.g., responding to all approximations of behavior with natural reinforcers) strategies within everyday activities and on an ongoing basis to increase skill development. These components are the basis for other intervention programs such as Prevent-Teach-Reinforce.102 Recent studies show that comprehensive intervention plans developed using the PTR model are effective to decrease challenging behavior and increase alternative behavior in young children and demonstrate that parents can effectively implement and generalize this intervention approach within family routines.103, 104 These PBS components have been integrated into other research as well. For example, Durand and colleagues17demonstrate the effectiveness of combining these core components of PBS with a cognitive behavioral therapy intervention to promote parental optimism.

Kazdin’s99 Parent Management Training is a forerunner in translating

behavioral principles into a comprehensive intervention approach for families.

Parents are taught specific behavioral strategies relevant to teaching and behavior

management such as praise, planned ignoring, time-out, and shaping within the

home context. Incredible Years, PCIT,

Triple P, and Multisystem Treatment

Foster Care follow suit and incorporate features of comprehensive behavior

support, as well as focus on preventing the coercive cycle. This is

accomplished in these programs by teaching parents’ prevention strategies

(e.g., increased praise and decreased criticism/commands, limit setting,

supervision/monitoring, relationship building), methods to model and prompt new

skills and positive behaviors, and specific reinforcement (e.g., structured

token economy system, increased attention to positive behavior and decreased

attention to negative behavior). A recent randomized clinical trial also

demonstrates the effectiveness of parent training that includes prevention,

teaching, and management strategies.105

Programs with Multiple PBS Components

Several books have

been written for professionals and parents specifically about parenting and

positive behavior support, combining these different features. They include

resources for professionals and parents. The first known resource related to

family PBS was Families and Positive

Behavior Support106, which included practical applications of

principles, case studies, and preliminary research in family contexts.

Hieneman, Childs, and Sergay107 made this information accessible for

parents in a self-guided problem-solving workbook that also offers suggestions

for universal supports. Durand and

Hieneman108 outlined a similar process for professionals working

with families entitled Positive Family

Intervention (that also includes cognitive-behavioral strategies to

overcome parental pessimism as a barrier to implementation). Durand109

wrote Optimistic Parenting to make these

approaches accessible to parents and added components of mindfulness and family

social support. Finally, as mentioned

earlier, Dunlap and colleagues102 have produced a Prevent-Teach-Reinforce for Families

manual written for practitioners working with families that outlines

comprehensive assessment and contextualized intervention approaches for home

and community settings.

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR PRACTICE

Over the years, ongoing research and field-based intervention with families has led to an increasing number of evidence-based clinical practices110. The way in which those practices are organized, selected, and delivered may be informed by both the principles of PBS and the growing body of literature on effective family support approaches. We offer the following recommendations based on this review:

Quality of life outcomes

Ensure that the goals of intervention are focused on quality-of-life improvements and fully embraced by the family – that they have social validity and contextual fit. Align goals with the families’ strengths, resources, needs, priorities, preferences, supports, and stressors. This means guiding, rather than directing, goal selection via processes of person and family-centered planning.

Family engagement

Engage all relevant family members and others whose involvement could influence the outcomes, valuing their input and rights as decision makers. Ensure their involvement in all aspects of the process of goal identification, assessment, plan design, implementation, and evaluation. Empower families to apply the principles (rather than just procedures) of PBS and become collaborative problem-solvers.

Comprehensive assessment

Conduct structured, comprehensive assessments to develop a valid understanding of immediate patterns and broader ecological variables affecting behavior within the family. Use the coercive family process95 framework to help families understand reciprocal interactions that may be maintaining problem behavior. Develop and utilize assessment tools36 to effectively and efficiently capture variables precipitating and maintaining behavior within families.

Support strategies and interventions

Develop support strategies and interventions based on the assessments that are truly individualized to children, parents, families, and the contexts in which they live. Use the patterns identified and the categories of proactive, teaching, and management strategies to scaffold plan design and as framework for selecting services. Help families select relevant, evidence-based strategies that fit their needs (rather than simply adopting programs or procedures to which they are exposed), encouraging individualized, creative solutions that are aligned with families’ goals, values, and culture.

Monitoring fidelity and outcomes

Rely on objective information to assess the fidelity of plan implementation, increases in desirable behavior, decreases in problem behavior, and changes in quality of life. In addition to using clinical judgment and standardized tools, create and use behavioral anchors to structure observations and interviews. Engage parents in evaluating progress, combining simple subjective ratings and feasible recording procedures to capture of specific, meaningful outcomes. Focus data collection not only on child behavior or parental skills, but also overall family functioning.

Tiered programs

Embrace the ecological multi-tiered

conceptualization of intervention. Recognize that supports may be focused on

the child within the family system, parent as a conduit for change, family as a

whole, and/or broader support systems. Establish tiered programs that offer information

and resources on PBS to all families, more tailored supports for those at risk

or struggling, and intensive individualized assistance for those with the most

significant challenges. Develop methods for “triaging” families, assessing

their response to intervention, and transitioning within a continuum of

services.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Positive behavior support offers a useful framework for selecting, integrating, and evaluating evidence-based behavior support practices. The focus on lifestyle enhancement and engagement of support and service providers increases the likelihood that interventions will be readily adopted and sustainable. Comprehensive assessments of both contextual issues affecting behavior and functions maintaining interactions among family members allows the tailoring of strategies to family needs, thereby increasing their effectiveness. Finally, employing proactive, teaching, and management strategies within typical family routines offers a conceptually sound and easily adoptable approach.

These features are evident in family-based intervention both within the PBS literature and broader parent education and support programs. What appears to be missing is a comprehensive, integrated model of service delivery that embraces all features equally. This gap may, in part, be due to a few barriers. First, families whose children may be having behavioral challenges have often been viewed as the problem, or as recipient of services, rather than true partners.111 Current best practice in behavioral intervention and family support emphasizes respect for the strengths, resources, needs, priorities, and perspectives of all participants, with interventionists embracing a more facilitative role.112 Unfortunately, these values are not always evident in practice.

Second, professionals from different disciplines have often worked within their own theoretical and pragmatic “silos”, making fusion of knowledge and practices challenging.113 To bring about lifestyle change, PBS often requires the integration of a variety of services and supports, but it has not always been clear how to make this integration feasible. Wraparound process and strengthening systems of care75, 79, must therefore become a fundamental part of behavior support within family contexts.

Third, families who need support most are often stressed and discouraged, making them less responsive to education and intervention.114 This barrier has been addressed through ‘adjunctive supports’ such as respite, social support, and additional therapies in parenting programs.115 More recently, cognitive behavior therapy techniques such as optimism training17, 108, mindfulness practice116, and related interventions such as Acceptance and Commitment Therapy117 and Cognitive Behavioral Family Intervention118 have been more fully embedded within behavioral intervention with families. These approaches not only address behaviors of concern, but help parents overcome emotional barriers to implementation of the plans.

And finally, PBS and other comprehensive interventions may be viewed as highly complex and time-consuming, driven by intensive data collection and circumscribed procedures that may seem difficult to implement fully.119 To be acceptable and feasibly adopted, PBS’s core components must be distilled and packaged within user-friendly resources that are readily accessible to families and professionals supporting them (see examples of brief resources on apbs.org-families). Progress is clearly being made in integrating PBS features into family-based behavior support, but more work needs to be done to bring a comprehensive approach to complete fruition.

Ethical approval: This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

References

1. Carr EG, Dunlap G, Horner RH, et al. Positive Behavior Support. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions. 2002;4(1):4-16. doi:10.1177/109830070200400102

2. Dunlap, G. Sailor, W., Horner, R. H., & Sugai, G. (2009). Overview and history of positive behavior support. In W. Sailor, G. Dunlap, G. Sugai, & R. Horner (Eds.), Handbook of positive behavior support (pp. 3-16). New York: Springer.

3. Horner RH, Dunlap G, Koegel RL, et al. Toward a Technology of “Nonaversive” Behavioral Support. Journal of the Association for Persons with Severe Handicaps. 1990;15(3):125-132. doi:10.1177/154079699001500301

4. Kincaid D, Dunlap G, Kern L, et al. Positive Behavior Support. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions. 2015;18(2):69-73. doi:10.1177/1098300715604826

5. Lucyshyn,, J. M., Dunlap, G., & Freeman R.(2015). A historical perspective on the evolution of positive behavior support as a science-based discipline. In F. Brown, J. Anderson, & R. De Pry (Eds.), Individual positive behavior supports: A standards-based guide to practices in schools and community-based settings (pp.3-25). Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes Publishing.

6. Lecavalier L, Leone S, Wiltz J. The impact of behaviour problems on caregiver stress in young people with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 2006;50(3):172-183. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2788.2005.00732.x

7. Neece CL, Green SA, Baker BL. Parenting Stress and Child Behavior Problems: A Transactional Relationship Across Time. American Journal on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities. 2012;117(1):48-66. doi:10.1352/1944-7558-117.1.48

8. Spratt EG, Saylor CF, Macias MM. Assessing parenting stress in multiple samples of children with special needs (CSN). Families, Systems, & Health. 2007;25(4):435-449. doi:10.1037/1091-7527.25.4.435

9. Pastor, P.N., Rueben, C.A., & Duran, C.R. (2012). Identifying emotional and behavioral problems in children aged 4-17 years: United States, 2001-2007. National Health Statistics Reports, 48, 1-18.

10. Einfeld SL, Tonge BJ. Population prevalence of psychopathology in children and adolescents with intellectual disability: II epidemiological findings. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 2007;40(2):99-109. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2788.1996.768768.x

11. Lowe K, Jones E, Allen D, et al. Staff Training in Positive Behaviour Support: Impact on Attitudes and Knowledge. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities. 2007;20(1):30-40. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3148.2006.00337.x

12. Alexander JF, Robbins MS, Sexton TL. The Journal of Primary Prevention. 2000;21(2):185-205. doi:10.1023/a:1007031219209

13. Sanders MR, Turner KMT, Markie-Dadds C. Prevention Science. 2002;3(3):173-189. doi:10.1023/a:1019942516231

14. E Mark Cummings, Davies P. Children and Marital Conflict : An Impact of Family Dispute and Resolution. Guilford; 1994.

15. Burke JD, Pardini DA, Loeber R. Reciprocal Relationships Between Parenting Behavior and Disruptive Psychopathology from Childhood Through Adolescence. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2008;36(5):679-692. doi:10.1007/s10802-008-9219-7

16. Chamberlain P, & Patterson, GR. (1995). Discipline and child compliance. In M. H. Bornstein (Ed.), Handbook of parenting: Applied and practical parenting (Vol. 4; pp. 205– 225). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

17. Durand VM, Hieneman M, Clarke S, Wang M, Rinaldi ML. Positive Family Intervention for Severe Challenging Behavior I. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions. 2012;15(3):133-143. doi:10.1177/1098300712458324

18. Webster-Stratton C, Reid MJ. Treating Conduct Problems and Strengthening Social and Emotional Competence in Young Children. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders. 2003;11(3):130-143. doi:10.1177/10634266030110030101

19. Horner RH, Carr EG. Behavioral Support for Students with Severe Disabilities. The Journal of Special Education. 1997;31(1):84-104. doi:10.1177/002246699703100108

20. Schwartz IS, Baer DM. Social validity assessments: is current practice state of the art? Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1991;24(2):189-204. doi:10.1901/jaba.1991.24-189

21. Wolf MM. Social validity: the case for subjective measurement or how applied behavior analysis is finding its heart1. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1978;11(2):203-214. doi:10.1901/jaba.1978.11-203

22. Schalock RL. The concept of quality of life: what we know and do not know. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 2004;48(3):203-216. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2788.2003.00558.x

23. Wehmeyer ML (2015). Strategies to promote self-determination. In F. Brown, J. L. Anderson, De Pry, R. L. (Eds.), Individual positive behavior supports: A standards-based guide to practices in school and community settings (pp. 319-332). Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes Publishing.

24. Benazzi L, Horner RH, Good RH. Effects of Behavior Support Team Composition on the Technical Adequacy and Contextual Fit of Behavior Support Plans. The Journal of Special Education. 2006;40(3):160-170. doi:10.1177/00224669060400030401

25. Bambara LM. & Kunsch C. (2014). Effective teaming for positive behavior support. In F. Brown, J. Anderson, & R. De Pry (Eds.). Individual positive behavior supports: A standards-based guide to practices in school and community-based settings (pp. 47-70). Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes.

26. Kincaid D. & Fox L. (2002). Person-centered planning and positive behavior support. In S. Holburn & P. Vietze (Eds.), Person-centered planning: Research, practice, and future directions (pp. 29-49). Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes Publishing.

27. Claes C, Van Hove G, Vandevelde S, van Loon J, Schalock RL. Person-Centered Planning: Analysis of Research and Effectiveness. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities. 2010;48(6):432-453. doi:10.1352/1934-9556-48.6.432

28. Bradshaw CP, Mitchell MM, Leaf PJ. Examining the Effects of Schoolwide Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports on Student Outcomes. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions. 2009;12(3):133-148. doi:10.1177/1098300709334798

29. Horner RH, Sugai G, Smolkowski K, et al. A Randomized, Wait-List Controlled Effectiveness Trial Assessing School-Wide Positive Behavior Support in Elementary Schools. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions. 2009;11(3):133-144. doi:10.1177/1098300709332067

30. Duchnowski, AJ, & Kutash K. (2009). Integrating PBS, mental health services, and family- driven care. In W. Sailor, G. Dunlap, G. Sugai, & R. Horner (Eds.), Handbook of positive behavior support (pp. 203-231). New York, NY: Springer.

31. McCart, A, Wolf N, Sweeney HM, Markey U, & Markey D J. (2009). Families facing extraordinary challenges in urban communities: Systems-level application of positive behavior support. In W. Sailor, G. Dunlap, G. Sugai, & R. Horner (Eds), Handbook of positive behavior support (pp. 257-277). New York, NY: Springer.

32. O’Neill RE, Hawken LS, & Burdock K. (2015). Conducting functional behavioral assessments. In F. Brown, J. L. Anderson, De Pry, R. L. (Eds.), Individual positive behavior supports: A standards-based guide to practices in school and community settings (pp. 259-278). Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes.

33. Wacker, DP, Berg WK. Harding JW, & Cooper-Brown LJ. (2011). Functional and structural approaches to behavioral assessment of problem behavior. In W. W. Fisher, C. C. Piazza & H. S. Roane (Eds.), Handbook of applied behavior analysis (pp. 165-181). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

34. Stichter JP, Hudson S, Sasso GM. The Use of Structural Analysis to Identify Setting Events in Applied Settings for Students With Emotional/Behavioral Disorders. Behavioral Disorders. 2005;30(4):403-420. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23889852

35. Anderson CM, Long ES. Use of a structured descriptive assessment methodology to identify variables affecting problem behavior. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2002;35(2):137-154. doi:10.1901/jaba.2002.35-137

36. O’Neill RE, Albin RW, Storey K., Horner RH, & Sprague JR. (2015). Functional assessment and program development for problem behavior: A practical handbook (3rd Edition). Stamford, CT: Cengage Learning

37. Durand, VM & Crimmins DB. (1992). The motivation assessment scale (MAS) administration guide. Topeka, KS: Monaco Associates.

38. Iwata BA & DeLeon IG. (1996). Functional analysis screening tool (FAST). Gainesville: Florida Center on Self-Injury, University of Florida.

39. Lewis TJ, Scott TM, Sugai G. The Problem Behavior Questionnaire: A Teacher-Based Instrument To Develop Functional Hypotheses of Problem Behavior in General Education Classrooms. Diagnostique. 1994;19(2-3):103-115. doi:10.1177/073724779401900207

40. Bijou SW, Peterson RF, Ault MH. A method to integrate descriptive and experimental field studies at the level of data and empirical concepts1. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1968;1(2):175-191. doi:10.1901/jaba.1968.1-175

41. Touchette PE, MacDonald RF, Langer SN. A scatter plot for identifying stimulus control of problem behavior. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1985;18(4):343-351. doi:10.1901/jaba.1985.18-343

42. Hanley GP, Iwata BA, McCord BE. Functional analysis of problem behavior: a review. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2003;36(2):147-185. doi:10.1901/jaba.2003.36-147

43. Iwata BA, Dozier CL. Clinical Application of Functional Analysis Methodology. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2008;1(1):3-9. doi:10.1007/bf03391714

44. Hieneman M & Dunlap G. (2015). Implementing multi-element positive behavior support plans. In F. Brown, J. Anderson, & R. De Pry (Eds.), Individual positive behavior supports: A standards-based guide to practices in schools and community-based settings (pp.417-431). Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes Publishing.

45. Todd AW, Algozzine B, Horner RH, & Algozzine K. (2014). Data-based decision making. In C. Reynolds, K. Vannest, & E. Fletcher-Janzen (Eds.), Encyclopedia of special education: A reference for the education of children, adolescents, and adults with disabilities and other exceptional individuals (4th ed.). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

46. Sanetti LMH, Dobey LM, Gritter KL. Treatment Integrity of Interventions With Children in the Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions From 1999 to 2009. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions. 2011;14(1):29-46. doi:10.1177/1098300711405853

47. Freeman R, Enyart M, Schmitz K, Kimbrough P, Matthews P, & Newcomer L. (2014). Integrating best practice in person-centered planning, wraparound, and positive behavior support to enhance quality of life. In F. Brown, J. Anderson, & R. De Pry (Eds.), Individual positive behavior supports: A standards-based guide to practices in school and community-based settings (pp 241-257). Baltimore, MD: Brookes Publishing.

48. Kincaid D, Knoster T, Harrower JK, Shannon P, Bustamante S. Measuring the Impact of Positive Behavior Support. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions. 2002;4(2):109-117. doi:10.1177/109830070200400206

49. Luiselli JK. Antecedent Assessment & Intervention: Supporting Children & Adults with Developmental Disabilities in Community Settings. Paul H. Brookes Pub; 2006.

50. Richman DM, Barnard-Brak L, Grubb L, Bosch A, Abby L. Meta-analysis of noncontingent reinforcement effects on problem behavior. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2015;48(1):131-152. doi:10.1002/jaba.189 1.

51. Shogren KA, Faggella-Luby MN, Sung Jik Bae, Wehmeyer ML. The Effect of Choice-Making as an Intervention for Problem Behavior. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions. 2004;6(4):228-237. doi:10.1177/10983007040060040401

52. Koyama T, Wang H-T. Use of activity schedule to promote independent performance of individuals with autism and other intellectual disabilities: A review. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2011;32(6):2235-2242. doi:10.1016/j.ridd.2011.05.003

53. Kern L, Choutka CM, Sokol NG. Assessment-Based Antecedent Interventions Used in Natural Settings to Reduce Challenging Behavior: An Analysis of the Literature. Education and Treatment of Children. 2002;25(1):113-130. http://www.jstor.org/stable/42900519

54. Wheeler JJ, Carter SL, Mayton MR, Chitiyo M. Preventing Challenging Behaviour through the Management of Instructional Antecedents. Developmental Disabilities Bulletin. 2006;34:1-14. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ815703

55. Durand VM, Carr EG. Functional communication training to reduce challenging behavior: maintenance and application in new settings. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1991;24(2):251-264Ti community (pp. 81-98). Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes.

56. Tiger JH, Hanley GP, Bruzek J. Functional Communication Training: A Review and Practical Guide. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2008;1(1):16-23. doi:10.1007/bf03391716

57. Baker BL, Brightman A. Steps to Independence: Teaching Everyday Skills to Children with Special Needs. Paul H. Brookes Pub. Co; 2004.

58. Athens ES, Vollmer TR. AN INVESTIGATION OF DIFFERENTIAL REINFORCEMENT OF ALTERNATIVE BEHAVIOR WITHOUT EXTINCTION. Thompson R, ed. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2010;43(4):569-589. doi:10.1901/jaba.2010.43-569

59. Ingram K, Lewis-Palmer T, Sugai G. Function-Based Intervention Planning. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions. 2005;7(4):224-236. doi:10.1177/10983007050070040401

60. Janney DM, Umbreit J, Ferro JB, Liaupsin CJ, Lane KL. The Effect of the Extinction Procedure in Function-Based Intervention. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions. 2012;15(2):113-123. doi:10.1177/1098300712441973

- Albin RW, Lucyshyn JM, Horner RH, Flannery KB. Contextual fit for behavioral support plans: A model of “goodness of fit” In: Koegel LK, Koegel RL, Dunlap G, editors. Positive behavioral support: Including people with difficult behavior in the community. Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes; 1996. pp. 81–98.

62. Hieneman M, Dunlap G. Factors Affecting the Outcomes of Community-Based Behavioral Support. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions. 2000;2(3):161-178. doi:10.1177/109830070000200304

63. Moes DR, Frea WD. Contextualized behavioral support in early intervention for children with autism and their families.Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2002;32(6):519-533. doi:10.1023/a:1021298729297

64. Smith-Bird E, Turnbull AP. Linking Positive Behavior Support to Family Quality-of-Life Outcomes. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions. 2005;7(3):174-180. doi:10.1177/10983007050070030601

65. Duda MA, Clarke S, Fox L, Dunlap G. Implementation of Positive Behavior Support With a Sibling Set in a Home Environment. Journal of Early Intervention. 2008;30(3):213-236. doi:10.1177/1053815108319124

66. Lucyshyn JM, Albin RW, Horner RH, Mann JC, Mann JA, Wadsworth G. Family Implementation of Positive Behavior Support for a Child With Autism. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions. 2007;9(3):131-150. doi:10.1177/10983007070090030201

67. Vaughn BJ, Clarke S, Dunlap G. ASSESSMENT-BASED INTERVENTION FOR SEVERE BEHAVIOR PROBLEMS IN A NATURAL FAMILY CONTEXT. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1997;30(4):713-716. doi:10.1901/jaba.1997.30-713

68. Sanders MR. Triple P-Positive Parenting Program as a public health approach to strengthening parenting. Journal of Family Psychology. 2008;22(4):506-517. doi:10.1037/0893-3200.22.3.506

69. Dishion TJ, Stormshak EA. Intervening in Children’s Lives : An Ecological, Family-Centered Approach to Mental Health Care. American Psychological Association, (Imp; 2007).

70. Dunst CJ, Trivette CM, Hamby DW. Meta-analysis of family-centered helpgiving practices research. Mental retardation and developmental disabilities research reviews. 2007;13(4):370-378. doi:10.1002/mrdd.20176

71. Jonkman CS, Schuengel C, Lindeboom R, Oosterman M, Boer F, Lindauer RJ. The effectiveness of Multidimensional Treatment Foster Care for Preschoolers (MTFC-P) for young children with severe behavioral disturbances: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2013;14(1):197. doi:10.1186/1745-6215-14-197

72. Leve LD, Fisher PA, Chamberlain P. Multidimensional Treatment Foster Care as a Preventive Intervention to Promote Resiliency Among Youth in the Child Welfare System. Journal of Personality. 2009;77(6):1869-1902. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6494.2009.00603.x

73. Nowak C, Heinrichs N. A Comprehensive Meta-Analysis of Triple P-Positive Parenting Program Using Hierarchical Linear Modeling: Effectiveness and Moderating Variables. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2008;11(3):114-144. doi:10.1007/s10567-008-0033-0

74. McEachern AD, Fosco GM, Dishion TJ, Shaw DS, Wilson MN, Gardner F. Collateral benefits of the family check-up in early childhood: Primary caregivers’ social support and relationship satisfaction. Journal of Family Psychology. 2013;27(2):271-281. doi:10.1037/a0031485

75. Clark HB, Clarke RT. Research on the wraparound process and individualized services for children with multi-system needs. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 1996;5(1):1-5. doi:10.1007/bf02234674

76. Tumbull AP & Turnbull HR. (1996). Group action planning as a strategy for providing comprehensive family support. In L. K. Koegel, R L Koegel, & G. Dunlap (Eds.), Positive behavioral support: Including people with difficult behavior in the community (pp. 99-114). Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes Publishing.

77. Walker JS, Schutte KM. Practice and Process in Wraparound Teamwork. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders. 2004;12(3):182-192. doi:10.1177/10634266040120030501

78. Clark HB, Hieneman M. Comparing the Wraparound Process to Positive Behavioral Support. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions. 1999;1(3):183-186. doi:10.1177/109830079900100307

79. Chamberlain P & Smith DK (2003). Antisocial behavior in children and adolescents: The Oregon multidimensional treatment foster care model. In A. E. Kazdin & J. R. Weisz (Eds.), Evidence-based psychotherapies for children and adolescents (pp. 282-300). New York: Guilford Press.

80. McCart A, Lee J, Frey AJ, Wolf N., Choi JH., Haynes H. (2010). Response to intervention in early childhood centers: A multitiered approach to promoting family engagement. Early Childhood Services, 4(2), 87-104.

81. Phaneuf L, McIntyre LL. EFFECTS OF INDIVIDUALIZED VIDEO FEEDBACK COMBINED WITH GROUP PARENT TRAINING ON INAPPROPRIATE MATERNAL BEHAVIOR. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2007;40(4):737-741. doi:10.1901/jaba.2007.737-741

82. Phaneuf L, McIntyre LL. The Application of a Three-Tier Model of Intervention to Parent Training. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions. 2011;13(4):198-207. doi:10.1177/1098300711405337

83. Sanders MR, Markie-Dadds C, Tully LA, Bor W. The Triple P-Positive Parenting Program: A comparison of enhanced, standard, and self-directed behavioral family intervention for parents of children with early onset conduct problems. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68(4):624-640. doi:10.1037/0022-006x.68.4.624

84. Turner KMT, Sanders MR. Dissemination of evidence-based parenting and family support strategies: Learning from the Triple P—Positive Parenting Program system approach. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2006;11(2):176-193. doi:10.1016/j.avb.2005.07.005

85. Webster-Stratton C. (2005). The incredible years: A training series for the prevention and treatment of conduct problems in young children. In: E. D. Hibbs, & P. S. Jensen (Eds.), Psychosocial treatments for child and adolescent disorders: Empirically based strategies for clinical practice (pp. 507–555). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

86. Webster-Stratton C, Hammond M. Treating children with early-onset conduct problems: A comparison of child and parent training interventions. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1997;65(1):93-109. doi:10.1037/0022-006x.65.1.93

87. Brinkmeyer MY & Eyberg SM. (2003). Parent-child interaction therapy for oppositional children. In A. E. Kazdin (Eds.), Evidence-based psychotherapies for children and adolescents (pp. 204-223). New York: The Guilford Press.

88. Fettig A, Barton EE. Parent Implementation of Function-Based Intervention to Reduce Children’s Challenging Behavior. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education. 2013;34(1):49-61. doi:10.1177/0271121413513037

89. Dunlap G, Newton JS, Fox L, Benito N, Vaughn B. Family Involvement in Functional Assessment and Positive Behavior Support. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities. 2001;16(4):215-221. doi:10.1177/108835760101600403

90. Fettig A, Ostrosky MM. Collaborating with Parents in Reducing Children’s Challenging Behaviors: Linking Functional Assessment to Intervention. Child Development Research. 2011;2011:1-10. doi:10.1155/2011/835941

91. Wacker DP, Lee JF, Dalmau YCP, et al. CONDUCTING FUNCTIONAL ANALYSES OF PROBLEM BEHAVIOR VIA TELEHEALTH. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2013;46(1):31-46. doi:10.1002/jaba.29

92. Dunlap G, Ester T, Langhans S, Fox L. Functional Communication Training with Toddlers in Home Environments. Journal of Early Intervention. 2006;28(2):81-96. doi:10.1177/105381510602800201

93. Lucyshyn JM, Albin RW, Nixon CD. Embedding comprehensive behavioral support in family ecology: An experimental, single case analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1997;65(2):241-251. doi:10.1037/0022-006x.65.2.241

94. Lucyshyn JM, Irvin LK, Blumberg ER, Laverty R, Horner RH, Sprague JR. Validating the Construct of Coercion in Family Routines: Expanding the Unit of Analysis in Behavioral Assessment with Families of Children with Developmental Disabilities. Research and practice for persons with severe disabilities: the journal of TASH. 2004;29(2):104-121. doi:10.2511/rpsd.29.2.104

95. Patterson GR. (1982). Coercive family process (Vol. 3). Eugene, OR: Castalia Publishing Company.

96. Eyberg SM, Funderburk BW, Hembree-Kigin TL, McNeil CB, Querido JG, Hood KK. Parent-Child Interaction Therapy with Behavior Problem Children: One and Two-Year Maintenance of Treatment Effects in the Family. Child & Family Behavior Therapy. 2001;23(4):1-20. doi:10.1300/j019v23n04_01

97. Herschell AD, Calzada EJ, Eyberg SM, McNeil CB. Parent-child interaction therapy: New directions in research. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2002;9(1):9-16. doi:10.1016/s1077-7229(02)80034-7

98. Barton EE, Fettig A. Parent-Implemented Interventions for Young Children With Disabilities. Journal of Early Intervention. 2013;35(2):194-219. doi:10.1177/1053815113504625

99. Kazdin AE. (2005). Parent Management Training: Treatment for oppositional, aggressive, and antisocial behaviors in children and adolescents. New York: Oxford University Press.

100. Moes DR, Frea WD. Using Family Context to Inform Intervention Planning for the Treatment of a Child with Autism. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions. 2000;2(1):40-46. doi:10.1177/109830070000200106

101. Koegel RL, Symon JB, Kern Koegel L. Parent Education for Families of Children with Autism Living in Geographically Distant Areas. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions. 2002;4(2):88-103. doi:10.1177/109830070200400204

102. Dunlap G, Strain PS, Lee JK., Joseph J, Vatland C & Fox LK. (2017). Prevent-Teach- Reinforce for Families. Baltimore, MD: Brookes Publishing.

103. Bailey KM, Blair K-SC. Feasibility and potential efficacy of the family-centered Prevent-Teach-Reinforce model with families of children with developmental disorders. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2015;47:218-233. doi:10.1016/j.ridd.2015.09.019

104. Sears KM, Blair K-SC, Iovannone R, Crosland K. Using the Prevent-Teach-Reinforce Model with Families of Young Children with ASD. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2012;43(5):1005-1016. doi:10.1007/s10803-012-1646-1 1.

105. Bearss K, Johnson C, Smith T, et al. Effect of Parent Training vs Parent Education on Behavioral Problems in Children With Autism Spectrum Disorder. JAMA. 2015;313(15):1524. doi:10.1001/jama.2015.3150

106. Lucyshyn JM, Dunlap G, & Albin RW. (2002). Families and positive behavior support: Addressing problem behavior in family contexts. Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes Publishing.

107. Hieneman M, Childs KE., & Sergay J. (2006). Parenting with positive behavior support: A practical guide to resolving your child’s difficult behavior. Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes Publishing.

108. Durand VM & Hieneman M. (2008). Helping parents with challenging children: Positive family intervention: Facilitator guide/Parent workbook. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

109. Durand VM. (2011). Optimistic parenting: Hope and help for you and your challenging child. Baltimore, MD: Brookes Publishing.

110. Kumpfer KL, Alvarado R. Family-strengthening approaches for the prevention of youth problem behaviors. American Psychologist. 2003;58(6-7):457-465. doi:10.1037/0003-066x.58.6-7.457

111. Elliott T, & Parker MW. (2012). Family caregivers and health care providers: Developing partnerships for a continuum of care and support. In R. C. Talley & J. E. Crews (Eds.), Multiple Dimensions of Caregiving and Disability (pp. 135-152). New York: Springer.

112. Madsen WC. (2007). Collaborative therapy with multi-stressed families. New York, NY: Guildford Press

113. Orchard CA, Curran V, Kabene S. Creating a Culture for Interdisciplinary Collaborative Professional Practice. Medical Education Online. 2005;10(1):4387. doi:10.3402/meo.v10i.4387

114. Whittingham K, Sofronoff K, Sheffield J, Sanders MR. Stepping Stones Triple P: An RCT of a Parenting Program with Parents of a Child Diagnosed with an Autism Spectrum Disorder. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2008;37(4):469-480. doi:10.1007/s10802-008-9285-x

115. Sanders MR, Bor W, Morawska A. Maintenance of Treatment Gains: A Comparison of Enhanced, Standard, and Self-directed Triple P-Positive Parenting Program. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2007;35(6):983-998. doi:10.1007/s10802-007-9148-x

116. Singh NN, Lancioni GE, Manikam R, Latham LL, & Jackman MM. (2014). Mindfulness-based positive behavior support in intellectual and developmental disabilities. In I. Iytzan & T. Lomas (Eds.), Mindfulness in positive psychology: The science of meditation and wellbeing (pp. 212-226). East Sussex: Taylor & Francis.

117. Hayes SC, Strosahl K, & Wilson KG. (1999). Acceptance and commitment therapy: An experiential approach to behavior change. New York: Guilford Press.

118. Sanders MR, McFarland M. Treatment of depressed mothers with disruptive children: A controlled evaluation of cognitive behavioral family intervention. Behavior Therapy. 2000;31(1):89-112. doi:10.1016/s0005-7894(00)80006-4 1.

119. Allen KD, Warzak WJ. The problem of parental nonadherence in clinical behavior analysis: effective treatment is not enough. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2000;33(3):373-391. doi:10.1901/jaba.2000.33-373.

Permission to be Reprinted:

Journal of Child and Family Studies. October 2017, 25(2): 1-14.

DOI: 10.1007/s10826-017-0813-6