Positive Approaches Journal, Volume 12, Issue 3

| Site: | My ODP |

| Course: | My ODP |

| Book: | Positive Approaches Journal, Volume 12, Issue 3 |

| Printed by: | |

| Date: | Saturday, January 31, 2026, 2:51 AM |

Positive Approaches Journal | 6

Volume 12 ► Issue 3 ► November 2023

Safe Spaces, Strong Supports: Multifaceted Approaches to Suicide Prevention and Mental Well-being

Introduction

In the spirit of Thanksgiving, the Editorial Board of the Positive Approaches Journal would like to share our gratitude to the dedicated contributors to the November 2023 issue, “Safe Spaces, Strong Supports: Multifaceted Approaches to Suicide Prevention and Mental Well-being.” Though each issue of the Journal maintains a focus on our Mission Statement as described on page 5, the topic of suicide seems to be particularly relevant as winter approaches and as stressful events loom large in all forms of media.

The generosity of time and talent of contributors to PAJ is, frankly, remarkable. The current issue is no exception in bringing together contributions from a diverse range of voices, expertise, and professional backgrounds. The current issue focuses important attention on the often under-recognized topic of suicide and individuals with intellectual disabilities and autism.

Knowledge brings new understanding, and new understanding brings new opportunities to be hopeful about better addressing the impact of suicidal thoughts and actions. In this issue the authors share their insights, experiences and resources which will aid in your support of others.

Gregory Cherpes MD,

NADD-CC

Medical Director

Office of Developmental

Programs

Department of Human Services

Amy

Alford, M.Ed., BCBCA

Clinical

Director

PAJ

Acting Editor-in-Chief

Office

of Developmental Programs

Department

of Human Services

Positive Approaches Journal | 7-13

Volume 12 ► Issue 3 ► November 2023

Data Discoveries

The goal of Data Discoveries is to present useful data using new methods and platforms that can be customized.

Suicide is a leading cause of death in the United States and suicide rates have increased about 36% since 2000.1 Suicide was the cause of death for more than 48,000 people in the US in 2021 alone, which translates roughly to one death every 11 minutes.1 Suicide impacts people of all ages. It is the second leading cause of death for children aged 10-14 and young adults between 20-34 years old.1 Millions of people attempt or make a plan to attempt suicide each year. In an effort to address this mental health crisis, the United States Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration's (SAMHSA) Center for Mental Health Services launched a revamped three-digit crisis and suicide lifeline: 988.2 The 988 crisis and suicide lifeline was launched in 2022 in an attempt to streamline support for people across the U.S. and provide resources to individuals experiencing a mental health crisis and those worried about someone experiencing a mental health crisis. The new abbreviated number was designed to be easy for people to remember during a crisis and to reduce barriers to support .3 988 , is a distinctive service because it offers "someone to talk to" , connecting individuals in crisis to trained counselors who provide emotional support and assistance. Over 98% of issues are resolved at the initial contact, eliminating the need for further dispatch of additional services.4 People can call, text, or chat online with a trained crisis counselor who will listen, provide support, and connect them with resources, as opposed to a 911 dispatcher who will engage other services like police or emergency medical services that may not be necessary.2

As 988 roll-out continues nationally, efforts to fund outreach will be critical to ensuring community awareness.3 Addressing misconceptions about mental health and suicide and spreading awareness about 988 through media channels is crucial to ensure connections to this important service, especially among people in minoritized and marginalized communities, such as in Black and Hispanic populations and people in the LGBTQI+ community.3 There are also gaps in funding that have made it challenging for states to effectively staff 988 call centers to answer calls, texts, and chats, which may be resulting in lower call answer rates in states like Alaska, Arkansas, Alabama, and South Carolina.5 However, it is important to note that calls not answered at the state leve, may be transferred to a national call center to be answered, in order to provide support to the caller.3 Finally, data collection regarding 988 usage, caller demographics, and the effectiveness of the provided support can be used to improve services, identify trends, and allocate resources more efficiently.3

The data dashboard presented below provides information and data about 988 and suicide in the U.S. The first tab provides age-adjusted suicide rates from 2010 to 2021 (rate per 100,000 population), including the percent change over that time per state in the U.S. The second tab has data on the variation between states in the percentage of calls answered out of the calls to 988 that were made. Finally, the third tab has links to resources relevant to 988 and suicide prevention.

Conclusion

The Autism Services, Education, Resources, and Training Collaborative (ASERT) is a resource and information hub geared towards autistic individuals and those with other intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD) and their family members, providers, and other supporters. ASERT has created a host of resources focused on mental health, including Be Well, Think Well, a resource collection designed to increase understanding of the impact of mental health diagnoses on autistic individuals. This bundle includes social stories created for autistic people, information about suicide and emergency situations, and more. The Policy Impact Project, an initiative out of the Policy & Analytics Center (PAC) at Drexel University, is focused on translating important policy information impacting autistic people and people with IDD into lay-friendly resources. This includes a series of blog posts focused on 988, including an overview of the program and unpacking some of the complexities and areas for growth.

References

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Facts About Suicide Accessed 2 October 2023, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Facts About Suicide.

2. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration's (SAMHSA). 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline. Accessed 2 October 2023, 988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline.

3. Caron C. Is the New 988 Suicide Hotline Working? The New York Times. Is the New 988 Suicide Hotline Working?

4. National Council for Mental Wellbeing. 988 and 911: Similarities and Differences. Accessed 10 October 2023, Similarities and Differences Between 988 and 911.

5. Saunders H. Taking a Look at 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline Implementation One Year After Launch. Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF). Accessed 2 October 2023, Taking a Look at 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline Implementation.

Morgan | 14-19

Volume 12 ► Issue 3 ► November 2023

Unintentional Harm is

Still Harm

Lisa Morgan M.Ed.,

CAS

Research has shown autistic people without an intellectual disability to be at a significantly higher risk of suicidal thoughts, attempts, and death than the general population, yet the professionals supporting people in suicidal crisis do not understand this truth (Newel et al., 2023). The result is unintentional harm (Autism Crisis Support | Lisa Morgan Consulting, n.d.).

Unintentional harm is rooted in misconceptions, stigma, and preconceived notions about autism and autistic people that are then reflected back to autistic people through the way professionals interact with them. It can be invalidation of their autism diagnosis (for example, uninformed people saying, “Aren’t we all a little autistic?”) or communicating with them using figurative language and then getting frustrated when the autistic person doesn’t understand what the professional meant. It can mean putting a supportive hand on their shoulder when they are distressed, not understanding that touch can be very dysregulating sensory-wise, and not at all comforting. It can be insisting on eye contact or refusing to turn down lights or turn off noise. It can be talking too fast and not making space for a slow processing speed due to high anxiety. While all these actions are done with the best of intentions, it's not supportive and is even unintentionally harmful to autistic people.

And still, unintentional harm is still harm.

Social communication between autistic and non-autistic people has its differences, and even more so when an autistic person is dysregulated and in crisis. Suddenly, the social nuances the autistic person could understand no longer make sense. Literal speech may be all the autistic person can understand while in a crisis. Being concise, using as few words as possible, and getting straight to the point shows kindness towards an autistic person in crisis, yet I’ve been told that this is rude by the professionals who do not believe me when I present on this subject.

An autistic person is not a neurotypical person with a little autism on top. Autistic people have an autistic brain. Their brain is structured differently. They think, communicate, and experience the world differently, so they need support that meets their needs, not standardized, evidence-based, best practice support for non-autistic people.

There are resources available that have been developed by subject matter experts (Autism Crisis Support | Lisa Morgan Consulting, n.d.). One in particular was an international team effort that resulted in a proposed set of warning signs of suicide for autistic people (Warning Signs of Suicide for Autistic People an Autism-Specific Resource Based on Research Findings and Expert Consensus, n.d.). The resource is beneficial in that there are scenarios for each warning sign describing what it can look like for an autistic person experiencing that warning sign. The importance of understanding how autistic people might express their crisis situation is crucial to giving them support that can potentially save their life.

For example, there’s a scenario that goes with the warning sign, “A new focus on suicidal talk, ideation, or death-related topics that are not a special interest,” explaining that an autistic person can be completely calm when they say they want to kill themselves. There may not be any preceding traumatic event, and they may not show any emotions externally, because it’s all happening internally for them (Palser et al., 2021). Many autistic people have reported not being believed, because to a non-autistic supportive person, there needs to be something that happened or a display of emotions equaling whatever the supportive person deems enough. The words of an autistic person must be as meaningful as any expected preceding traumatic event, display of emotions, or whatever other criteria suggests a crisis to non-autistic people. Let me say that again because it’s excruciatingly important.

“The words of an autistic person must be as meaningful as any expected preceding traumatic event, display of emotions, or whatever other criteria suggests a crisis to non-autistic people.”~ Lisa Morgan

There’s another scenario that goes with the warning sign, “Sudden or increased withdrawal,” where an autistic person withdraws more than usual, is still not regulated, yet can still do all their school, work, or social activities. Professionals supporting autistic people need to understand that for autistic people, continuing to attend all their regular activities is not an indication that they are doing well. This could be the case, but what might also be happening is that change is too hard for that autistic person because they are struggling mentally, emotionally, or psychologically. It could be that it takes too much energy to adjust their schedule to meet their need to withdraw more, because of cognitive inflexibility or an aversion to change. Supportive professionals need to know and understand both possibilities.

The last scenario I will discuss goes with the warning sign, “No words to communicate acute distress.” The scenario explains that an autistic person who can verbally communicate may lose the ability to communicate as they go deeper, more severely into a crisis situation. The autistic person may still be able to talk about things that do not have to do with the crisis they are experiencing, but they are still in crisis. The autistic person may be very quiet and look calm, possibly peaceful, but a raging emotional storm could be going on internally. When this is happening, they need support just as if they are exhibiting extreme external behaviors and yelling that they are going to harm or kill themselves. Professionals need to understand this when supporting autistic people in crisis. It’s imperative they do not misunderstand a quiet, calm autistic person as being ok. It is also imperative they do not misunderstand a quiet, calm autistic person as being in crisis when they are just calm and quiet. The difference is in the change. The support is in knowing the possibilities of what might be happening for the autistic person they are helping. The change between being verbal and then suddenly becoming non-verbal and quiet. To support an autistic person who is experiencing this, offer them other means to communicate such as emojis, drawing, an assistive device, or writing.

Autistic people need to be supported as autistic people. It seems simple, doesn’t it? Yet they continually experience unintentional harm by well-meaning professionals, who use all the knowledge they learned to help the general public with the autistic people they support, instead of what the autistic person actually needs. Using general knowledge of how to support non-autistic people doesn’t always help a different-thinking person. It’s supportive to see the person before you. Allow the autistic person space to help you help them. Be culturally humble and learn what you can so that you can be supportive and help, and not unintentionally harm them.

References

1. Autism Crisis Support | Lisa Morgan Consulting. (n.d.). Autism and Suicide. Individualized Workshops for Professionals and Life Coaching for Autistic People.

2. Newell, V., Phillips, L., Jones, C., Townsend, E., Richards, C., & Cassidy, S. (2023). A systematic review and meta-analysis of suicidality in autistic and possibly autistic people without co-occurring intellectual disability. Molecular Autism, 14(1). A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.

3. Palser, E. R., Galvez-Pol, A., Palmer, C. E., Hannah, R., Fotopoulou, A., Pellicano, E., & Kilner, J. M. (2021). Reduced differentiation of emotion-associated bodily sensations in autism. Autism, 136236132098795. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361320987950

4. Warning Signs of Suicide for Autistic People An autism-specific resource based on research findings and expert consensus. (n.d.). Warning Signs of Suicide for Autistic People.

Biography

Lisa Morgan is a subject matter expert and advocate for crisis support and suicide prevention for autistic people. She develops autism specific resources in collaboration with the Autism and Suicide Workgroup she founded in 2017. Lisa presents trainings to professionals based on the resources and her lived experience of being a suicide loss survivor of her husband of 30 years in 2015. Lisa has a master’s degree in the Art of Teaching and is currently pursuing a master’s degree in social work. An autistic adult diagnosed later in life at 48 years old, Lisa is passionate about using autistic strengths to support autistic people in crisis.

Contact Information

lisamorganconsulting@gmail.com

Mowery, Milani, Rosen | 20-28

Volume 12 ► Issue 3 ► November 2023

From

A Suicidal Youth to Working in Youth Suicide Prevention:

An

Outline of the Pennsylvania Garrett Lee Smith Grant

O.A. Mowery, Rose A. Milani, Perri Rosen

Youth suicide prevention is a bit like the Swiss cheese model,1 and I once almost fell through the holes. I was backstage at my local Christian theater the first time I had a suicidal thought; a month shy of 14. That moment was fleeting—thankfully—but as I made my way through high school, my stress compounded, and my brain coped by devising other ill-wrought plans. I don’t know if I would be here today if not for a stern but kind AP English teacher who personally reached out to my mother with her concerns about my teariness in class. She also connected me with the Student Assistance Program (SAP),2 which helped me get the support I needed. Of course, not every student has a Miss Muntz, and if we think of the Swiss cheese model, she was only one slice. While it takes just one person to notice that a child is struggling, it still requires a team effort to connect them to care. Preventing youth suicide requires a holistic, cross-systems perspective, which is why I am proud to be a research coordinator on the Pennsylvania Youth Resource for Continuity of Care in Youth Serving Systems and Transitions (PRCCYSST) project, funded by the Garrett Lee Smith Youth Suicide Prevention Grant (GLS), so that I can contribute to efforts to improve care for other Pennsylvania youth at risk of suicide.

This grant is the fourth iteration that has been awarded to Pennsylvania’s Department of Human Services’ Office of Mental Health and Substance Abuse Services (OMHSAS) by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). It is a five-year grant, now in its final year, focused on continuity of care across youth-serving systems for those at risk of suicide. When someone is experiencing a suicide-related crisis, multiple systems are typically involved. For instance, they may initially be identified at home, at school, or in their community (e.g., by a primary care physician). Once identified, that youth may be referred to the crisis system or an emergency department for further evaluation. They may then be connected with various mental health treatment services (e.g., inpatient, outpatient, etc.). If admitted to an inpatient hospital, the youth and their family follow a similar pathway once the crisis is resolved, wherein they may be linked with additional supports (e.g., Student Assistance Program) and/or treatment options (e.g., outpatient) as they return to school. Within this project these pathways are referred to as the “pre-care” and “post-care” pathways. These pathways rely on effective cross-systems communication and collaboration. The grant team members from OMHSAS, Thomas Jefferson University, Drexel University, and the University of Pittsburgh have partnered with leadership in 16 different counties to bolster these pathways as a primary goal of the project.

This work is based upon Zero Suicide,3 a seven-part framework created by the National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention, the Suicide Prevention Resource Center, and other national experts in suicide prevention. Based on a longitudinal research study that found that 83% of individuals who died by suicide had a healthcare visit in the year prior to their death,4 Zero Suicide asserts that suicides are preventable for individuals within healthcare systems. The seven facets of this comprehensive approach to suicide prevention are to lead system-wide culture change (LEAD), train a competent and caring workforce (TRAIN), identify individuals at risk (IDENTIFY), engage at-risk individuals using a care plan (ENGAGE), treat suicidal thoughts and behaviors (TREAT), transition individuals with warm hand-offs (TRANSITION), and improve policies and procedures (IMPROVE). While Zero Suicide was created with the intent of being used in healthcare settings, our team has attempted to broaden it to assess and impact change from a systems-perspective across an entire county. Not only have we applied the framework to multiple systems (e.g., schools, SAP liaison agencies, primary care, law enforcement, crisis services, emergency rooms, inpatient psychiatric hospitals, outpatient agencies, county human services, and suicide prevention task forces), but we have also worked to adapt the framework to have a focus on youth.

The team’s approach to working with each county has involved four phases. Phase One included what we called “needs assessments” which were adapted from the original Zero Suicide Organizational Self-Study5 to fit the context of each of the systems involved. This survey was referred to as the Pennsylvania Organizational Self-Study, or POSS. One of the tenants of Zero Suicide is that each organization or entity will have different needs, so an evaluation is critical to successful implementation. Within each county, we worked with mental health leadership to develop rosters of organizations and lead contacts within each of the youth-serving systems to complete the survey. Organizations were assessed for strengths and needs regarding comprehensive suicide prevention by responding to questions on a continuum of best practices in accordance with Zero Suicide. Responses were presented as text where the first response was baseline and the fifth response showed best practice, to which participants indicated the option that best reflected their organization’s level of prevention efforts related to that specific question. Their responses helped identify strengths and needs regarding training, screening, assessment, organizational policies and procedures, treatment, and prevention practices. We also utilized the county rosters to build county-specific network analysis surveys, which aimed to identify the connections between organizations in regard to supporting youth at risk of suicide. These surveys were referred to as the Pennsylvania Network Analysis (PANA). Survey respondents identified all organizations that they had connected with while supporting a youth experiencing a suicide-related crisis for either “pre-care” or “post-care,” as well as for other relevant indicators such as data sharing and exchange of services. Our evaluation partners then conducted a network analysis illustrating the relationships between organizations within each county. Sharing these visual network maps back with county leadership leads to valuable insight, such as showing a particular hospital being underutilized while another was overburdened, for example.

Results of the POSS and the PANA were presented back to the counties in Phase Two, which focused on local strategic planning. The primary goal of Phase Two was to reflect on the data collected, gather input to help identify youth suicide prevention priorities, and discuss strategy ideas for the priority areas, all while engaging a diverse group of stakeholders within each county. This led to the development of a strategic plan that would serve as an anchor for implementation and sustainability. County leadership expanded their original rosters of those whom they asked to complete the survey, in order to incorporate additional stakeholders and community partners, including those with lived experience. All identified stakeholders were then invited to two strategic planning meetings. At the first meeting, the grant team facilitated discussion among smaller system-specific groups, utilizing aggregate data on the strengths and needs identified for each system. Stakeholders within these groups were asked to reflect on the data and identify areas of priority. Following this meeting, all priority areas were consolidated and presented back to county leadership, who then identified two to three areas of focus. Stakeholders were then invited to a second meeting in which those areas of focus were presented back to them. Then, in cross-systems breakout groups, stakeholders were asked to consider each priority area and identify key efforts or resources already in place, as well as barriers to improvement. They then had the opportunity to brainstorm strategies for implementation of that priority area. Following these meetings, the grant team worked to develop a draft of a strategic plan for county leadership to reflect on and decide to adopt, often with additional input from their stakeholders.

Phase Three of the project involved supporting counties as they refined their action plans and began strategy implementation within one or more of their goals. Because Pennsylvania is a commonwealth, every county is unique and thus each county’s approach to their strategic action plan has been unique. Some counties established suicide prevention task forces or other local coalitions to oversee and implement aspects of their plan, while others have focused their efforts on strengthening infrastructure as a first step through expanding, diversifying, and/or restructuring their local task forces. In this phase, the grant team met regularly with each county to provide technical assistance in support of their plans. In some cases, the grant team offered direct support, such as for training or screening efforts, and in other cases the team provided consultation or feedback on local resource development or further data collection efforts.

In our current and final phase of the project, the focus has been sustainability of the strategic plan and key strategies. For some counties, Phase Four has involved readministering the POSS and PANA surveys in order to evaluate system-specific changes as well as cross-organizational connections that may have evolved over the course of the project. For other counties this phase has involved continuing to strengthen infrastructure to support implementation of the strategic plan beyond the end of this project, as well as further technical assistance from the grant team to identify methods for expanding or sustaining prioritized local initiatives.

In this final year of the grant, the project team is also conducting analyses to look at overall impact, and the feedback from our partner counties has been positive thus far. Additionally, we have begun to identify common themes that have emerged across counties, which we collectively discuss at monthly cross-county meetings. Stakeholders across counties have emphasized the need for increased communication across systems, including the standardization of documents and screening tools. There has also been a resounding need across multiple counties for resources specifically created for youth and families who are in crisis. We are working in partnership with statewide family support organizations to create resources for families that will then be distributed to our partner counties for their adaptation and use. An additional goal of the grant team in this final year of the project is to create a toolkit, so that other counties in the commonwealth can implement these efforts on their own.

Our goal in this project has been to support and work closely with our partner counties to enact change through a multi-disciplinary, multi-system approach to suicide prevention. Rather than just focus on schools or primary care as we have done with previous GLS grants, we sought to collaborate with counties in engaging multiple systems, bringing them into a shared conversation about comprehensive youth suicide prevention both within and across organizations. While Zero Suicide has provided us with a helpful framework for doing this work, we also hope that it becomes a shared language across systems, thus improving communication and collaboration. All our efforts are made to support youth at risk of suicide and their families by improving the continuity of care to keep them from falling through the gaps.

References

1. Grumet J, Hogan M. The Emerging Zero Suicide Paradigm: Reducing Suicide for Those in Care. National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention. Aug 28, 2014. The Emerging Zero Suicide Paradigm.

2. Pennsylvania Network for Student Assistance Services. What is the student assistance program? 2019. What is the Student Assistance Program?

3. Education Development Center. (2015). Homepage: Zero suicide. Zero Suicide. 2015. Zero Suicide Practices Reduce Suicides Study.

4. Ahmedani, B.K., Simon, G.E., Stewart, C. et al. Healthcare visits prior to death - Health Care Contacts in the Year Before Suicide Death. J GEN INTERN MED. 2014;29: 870–877. Health Care Contacts in the Year Before Suicide Death Study.

5. Zero Suicide Organizational Self-Study. Education Development Center. 2015. Zero Suicide Organizational Self-Study.

Biographies

O.A. Mowery (they/them) is a research coordinator at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Proudly from Harrisburg PA, they moved to Philadelphia while attending La Salle University, where they earned a B.S. in Biology. They are currently studying for their Master’s in Public Health degree at Thomas Jefferson University, in addition to working there. Email: olivia.mowery@jefferson.edu

Rose Milani (she/her) has been working in the field of suicide prevention for the last 10 years. She has served as project coordinator and now program director for the Garrett Lee Smith Youth Suicide Prevention Grant in Pennsylvania. She assists in facilitating the Higher Education Suicide Prevention Coalition and is on the executive board of the Delaware Valley Medical Student Wellness Collaborative. She is currently getting her Master’s in Public Health from Thomas Jefferson University. Email: rose.milani@jefferson.edu

Dr. Perri Rosen (she/her) is a consulting psychologist at the Pennsylvania Office of Mental Health and Substance Abuse Services (OMHSAS) at the Department of Human Services (DHS) in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. She is also a Nationally Certified School Psychologist (NCSP) and licensed psychologist in Pennsylvania. Dr. Rosen co-chaired the Governor's Suicide Prevention Task Force, which was launched in May 2019, and she has remained part of the state leadership team for the Task Force. At OMHSAS, Dr. Rosen has also helped lead several school and community-based youth mental health and suicide prevention initiatives, including the Garrett Lee Smith Youth Suicide Prevention grant and the Pennsylvania Network of Student Assistance Services. Email: c-prosen@pa.gov

Contact Information

Questions/comments? Reach out to olivia.mowery@jefferson.edu

Hollins-Sims, Kuren, Milakovic | 29-37

Volume 12 ► Issue 3 ► November 2023

The Power of Belonging: How to Create Supportive Learning Environments That Reduce Suicide Risk

Pennsylvania Department of Education - Office for Safe Schools

Dr. Nikole Hollins-Sims, Dr. Scott Kuren, Dr. Dana Milakovic

Abstract

The Office for Safe Schools at the Pennsylvania Department of Education (PDE) is focused on creating supportive learning environments for every learner in the commonwealth. As an office dedicated to safety, educational approaches centered in equitable trauma-informed practices, seek to address physical and psychological safety. As the office has evolved over time, it now primarily focuses on promoting inclusivity, connection and belonging through cultivating relationships of care, support, and safe environments. These key tenets are imperative for reducing suicide risk in youth from a preventative and systemic approach.

Keywords: Belonging, Trauma-Informed, Safety

The Power of Belonging: How to Create Supportive Learning Environments That Reduce Suicide Risk

Supportive learning environments across the educational ecosystem are the place for learners to engage with others, learn how to become self-directed citizens, and develop academic skills for adulthood. In addition, learning environments can serve as a place where learners can feel connection, experience belonging, and create inclusive communities. The Office for Safe Schools at the Pennsylvania Department of Education (PDE) works collaboratively with Pennsylvania school communities and vested partners to advance efforts to develop and sustain equitable trauma-informed learning environments that promote and support the academic, physical, and psychological safety and well-being of all students and staff.

Over the past years (2017-2023), the Office for Safe Schools has evolved in a variety of ways. As schools continue to be places where learners are experiencing academic, social, emotional and behavioral interactions, the Office for Safe Schools has focused on explicitly integrating physical and psychological safety, with the understanding that physical safety alone could not be the primary focus of our public-facing work. Learners show up in schools as whole beings, and seeking ways to address each of these valuable domains of life are paramount. While the office is bound to specific laws and regulations that guide portions of the work, the ways in which these initiatives and practices are communicated to the educational community becomes an imperative and significant role of the office.

For example, Act 71 was signed into Pennsylvania law on June 26, 2014. Act 71 is dedicated to Youth Suicide Awareness and Prevention and Child Exploitation Awareness. “This law, which added section 1526 of the School Code, 24 PS § 15-1526, specifically requires school entities to: (1) adopt a youth suicide awareness and prevention policy; and (2) provide ongoing professional development in youth suicide awareness and prevention for professional educators serving students in grades 6-12. Additionally, section 1526 specifically permits school entities to incorporate curriculum on this topic into their instructional programs pursuant to their youth suicide awareness and prevention polices.” 1 Although Act 71 is specific to suicide prevention, the guidance and curriculum that accompany the law are aligned with other proactive and preventative guidance that schools are expected to put in place for safety purposes. Act 44 signed into law on June 22, 2018, is an example of where schools are required to (a) Appoint School Safety and Security Coordinators; (b) Establish mandatory school safety training for school entity employees, and (c) Establish standards for school police, school resource officers, and school security guards. To illustrate the importance of psychological, emotional and physical safety, these requirements are aligned and integrated with situational awareness, trauma-informed educational awareness, behavioral health awareness, suicide prevention/awareness, bullying prevention and awareness, substance use awareness, and emergency training drills. In June 2022, Act 55 amended Act 44 to increase the training requirement for school personnel to three hours annually for these topics, based on the needs of the school environment.

These examples of mandates for schools serve as an avenue for the Office for Safe Schools to articulate ways for schools to be intentional, and is creating safe and supportive learning environments. When implemented with fidelity, these educational systems can create equitable, inclusive, and trauma-informed spaces of belonging. Since the onset of the global pandemic in 2020, the Office for Safe Schools has sought to equip elementary and secondary schools with the necessary tools to align their efforts in proactive ways, and sustain climates of care for learners, staff and communities. Fall 2020 saw the release of the PDE Equitable Practices Hub, which served as a one-stop shop repository of resources dedicated to establishing and sustaining equitable practices in education. Organized around six pillars of practice, the hub offers resources aligned to specific spheres of influence. These include, school/district, classroom, and the individual educator, with each sphere represented in the following pillars of practice: (1) General Equity Practices, (2) Self-Awareness, (3) Data Practices, (4) Family/Community Engagement, (5) Academic Equity, (6) Disciplinary Equity. Although the audience for the hub extends beyond educators, the primary users have been teachers, administrators, and student support service providers (school counselors, school psychologists, etc.) The ultimate goal of creating equitable learning environments is to create inclusive communities that produce spaces of belonging. Given the ongoing work for the Office for Safe Schools related to school climate, social-emotional learning, trauma-informed practices, equitable practices, bullying prevention, and alcohol and other drugs prevention, the focus on aligning these supports in a comprehensive equitable and trauma-informed approach was necessary at a time when educators needed streamlined and clear approaches to their work.

In 2019, the Office for Safe Schools launched a dedicated MH webpage in an effort to be responsive to the educational field, inclusive of students, staff, families and communities. Resources provided to the field were a compilation of supports for mental health, social and emotional learning, suicide prevention, and grief and loss. Supports were linked to other state agencies to reduce the need for schools, families, and staff to navigate multiple state agency websites. In 2020, as families and students struggled to adapt to a changing world, this page was updated to provide targeted supports for families and students. This included self-care for educators, families, and students; support for families in dealing with emotional youth while they were struggling with emotions; and support in developing positive online learning environments. As schools began to physically re-open in 2021, it became more evident there was a need for supports around mental wellness, suicide prevention, and self-care. Updates were made to align with reopening guidance, and mental health was integrated into the Accelerated Learning Plan developed by PDE.

In addition, the traditional way of supporting schools and districts was revamped from a siloed delivery system of support to a cohesive and collaborative cascade model. For years, the intermediate units, which offer regional professional development and coaching to schools and districts, connected to PDE through a state system of support (SSOS). The Office for Safe Schools would initiate content and direction for each of the intermediate unit’s individual point of contact, who was then responsible for communicating to their team and local area school districts necessary training and content by topic. For example, the PDE lead for bullying prevention would connect with the 29 intermediate unit points of contact (POCs) assigned to bullying prevention and ensure that the most up-to-date information and training content was available and accessible to each POC. There was a lead for bullying prevention, school climate, equity, mental health/Student Assistance Program (SAP), school safety, etc. As one can imagine, many of the intermediate unit points of contact were responsible for many different areas of focus. While this approach is necessary, given the needs in the educational field, it unfortunately did not create an understanding of the interconnectedness of many of these initiatives and processes. The year 2021 was a year of significant change in education, and the Office for Safe Schools recognized the need for positive change as well. The need to streamline processes and convey the importance of connected approaches was evident and expressed by the educators attempting to deliver services to the best of their abilities in an ever-changing societal climate. The Office for Safe Schools dedicated time to engaging in an overhaul of the service delivery model previously established through the state system of support and established the Social-Emotional Wellness (SEW) system of support across the 29 intermediate units. In this new iteration of supports, each intermediate unit maintained a point of contact. The primary role was to align efforts related to trauma, equity, school climate, and bullying prevention into one connected stream of support. Students engaging in schools each day do not attend as one piece of their profile (e.g., academic, social-emotional, behavioral), but rather as a complete being seeking connection and community in their school environment. This knowledge informed the shift toward a complete approach to efforts in creating learning environments where students, staff, families and communities have the access and opportunity to experience school in a positive way. Currently, the SEW supports offered to schools and districts focuses on making explicit connections in centering equitable, trauma-informed practices to create supportive learning environments. The goal is to make transformative systems changes in schools, where students ultimately know that they are in a place of safety and care. Suicide prevention is nuanced and necessary. At the macro-system level there are many opportunities for educational, health, human service and economic agencies to influence and impact how to reduce the risk of suicide in youth. Safe, supportive and responsive learning environments can serve as the core of these influences and offer a safe haven for students to feel human connection that promotes mental wellness, cultural humility, and belonging.

References

Pennsylvania Department of Education. Accessed September 28, 2023 Act 71 - Youth Suicide Awareness and Prevention and child Exploitation Awareness Education (pa.gov).

Biographies

Dr. Nikole Hollins-Sims, Learning Environment Consultant, is a certified school psychologist and former special assistant to the secretary of education in Pennsylvania for equity, inclusion and belonging. She also serves as a partner for the national center on Positive Behavior Interventions and Supports (PBIS).

Dr. Scott Kuren, Director of the Office for Safe Schools, is a former Director of Pupil Services and worked in the field for over 20 years. He started his career in education working in a small sub-urban school district then transitioned to a large district with 19 schools that provided education to over 12,000 students. As the Director for the Office of Safe Schools, Dr. Kuren works collaboratively with Pennsylvania school communities and stakeholders, to advance efforts to develop and sustain equitable trauma-informed learning environments that promote and support the academic, physical, and psychological safety and well-being of all students and staff.

Dr. Dana Milakovic, Mental Wellness and Trauma Specialist, is a nationally certified school psychologist and trauma specialist. She also serves Pennsylvania on the leadership team of HEAL PA and is a PREPaRE Crisis prevention and response trainer.

Contact Information

Email: skuren@pa.gov

Physical Address: 607 South Drive, Harrisburg PA 17120

Phone Number: (717) 783-6788

Liddle | 38-44

Volume 12 ► Issue 3 ► November 2023

Suicide, Self-Harm & Risk-Taking: The Tragic Dangers that Social Media Poses to Children

Angela Liddle

Abstract

Since the introduction of MySpace in the late 1990s, social media has become an integral part of our lives. This is especially true for today’s children and teens, who spend many hours per day on social media platforms. Studies show that this constant usage is impacting children’s mental health, and this can lead to tragic, sometimes fatal, consequences for families. This article from Pennsylvania Family Support Alliance (PFSA) discusses what parents and families can do to ensure their children remain safe, healthy, and protected in this digital era.

--

At age 16, Chase Nasca seemed to have it all. The Long Island, New York teenager was “handsome, athletic, smart and funny,” according to his family. Chase’s promising life was cut short on February 18, 2022, when the teen took his own life. After his death, Chase’s family discovered that his TikTok feed was filled with thousands of unsolicited videos that showed violence, suicide, and self-harm.1

Social media has become an integral part of all our lives but has been particularly adopted by our children and youth. Tweens aged 8 to 12 average four or more hours per day and teens aged 13 to 18 spend more than eight hours per day on their screens and devices, thanks in part to the COVID-19 pandemic, which caused kids to turn to their screens to connect with friends or entertainment.2 Policymakers at the state and federal levels have proposed bans and restrictions on social media platforms, namely TikTok, in the interests of national security and protecting our children.

Legislation alone, however, is not enough to protect our kids. Parents and families must be equipped with the resources and tools to strengthen them to raise healthy children in a digital era. Social competence, after all, is a much better form of safety than avoidance.

Social Media and Mental Health

Excessive use of social media platforms can have very negative impacts, particularly on children and youth. But just as the impacts are important to understand, so are the reasons for why such a large portion of youth use social media excessively. For example, “dark patterns” help to explain some of the reasons why youth seem to have trouble putting down their device and staying off social media platforms. Dark patterns are user interfaces whose designers knowingly confuse users, make it difficult for users to express their actual preferences, or manipulate users into taking certain actions.3 The main areas where dark patterns are prevalent are social media, games, and ecommerce.4 Examples of dark patterns on social media platforms include infinite scrolling, autoplay features, and pull-to-refresh.5 These intentional designs enhance user engagement and begin to interfere with or even impair user autonomy, leading to excessive use.

Social media platforms use several factors to decide what content to serve a user. In TikTok’s case, it considers, among other attributes, how users interact with the app, such as which accounts they follow, comments they post, and videos they’ve liked or shared; the ads a user looks at; and the types of videos that a user creates.6 Accidentally clicking the wrong ad or viewing an inappropriate video can have severe consequences, such as contributing to depression and anxiety in teens, or memory loss.7 “For teens and children, the TikTok algorithm may be too effective,” noted a June 2023 article from Discover Magazine.8 “Reading a teen's innermost thoughts — especially when their vulnerable minds are drawn to harmful content — can lead them to see more problematic content.”

Family Digital Wellness

Social media use by teens has increased, and continues to increase, year after year. In fact, the share of teens who say they are online almost constantly has roughly doubled since 2014-15 (46% now and 24% then). When asked about the amount of time they spend on social media, just 8% of teens think they spend too little time on these platforms.9 This is why family digital wellness matters.

Between the ever-increasing access to technology-enabled devices and the lagging behind-nature of research, it is imperative that we begin to equip families—children and caregivers—with the necessary education and training to become competent in building safe and healthy interactions with technology. Every phase is important, from basic safeguards against potential harm, to understanding how our daily behaviors impact our overall well-being. Families in today’s digital era should focus on collective awareness, resilience, and competence—not avoidance—as the best way to keep kids safe online.

Case Study: PFSA Family Digital Wellness

PFSA is a nonprofit organization dedicated to child abuse and neglect prevention through education, training, and programming services. Knowing that lawmakers were floating bans and prohibitions, and seeing studies that showed the dangers of social media, we felt it was imperative to equip parents and families to recognize warning signs of digital threats, while learning how to create a foundation for safe, healthy relationships, and interactions with digital technologies.

To that end, we launched in 2022 the Family Digital Wellness initiative, an inclusive, supportive, and preventative approach aimed to strengthen families in raising healthy children in a digital era. The Family Digital Wellness hub on our website includes several resources to help parents and families, including a Parent Toolkit that features easy-to-implement solutions for families; practical guides and informational packets to help parents and families navigate the social media age; and up-to-date news and media stories regarding social media trends, policy updates, and examples of digital threats.

Advice

- Do not punish your children for using social media or threaten to take away their devices and screens. This will only help to make social media more attractive to them, especially teenagers.

- Learn to recognize common digital dangers, such as your child being secretive or anxious about their phone; or they become sad, upset, or angry when using their device.

- Monitor your child’s general mood changes and behaviors for signs of increased anxiety or depression.

- Become involved in the apps and games your child uses or has an interest in.

- Remind your child that you are a support and, at any point in a difficult situation, they can come to you without worrying about getting into trouble.

- Teach your child to assume everything they post online is public and teach them not to say anything online that they wouldn’t say in real life.

- Help your child create and protect passwords, making them hard for others to guess.

- Encourage your child to tell an adult if they encounter anything online that makes them feel uncomfortable or that they think is inappropriate.

- Make a habit of regularly checking your child’s privacy and filter settings in social media apps.

- Show your child how image filters can distort the reality of photos we see online and on social media.

Conclusion

Social media is here to stay. It is incumbent upon us as parents and guardians to help our children foster safe, healthy behaviors when they use these technologies. By doing so, we can make sure the next generation is better equipped for the good, and the bad, that comes with the use of social media. The mental health of our children and youth depends on it.

References

1. Carville O. Bloomberg - TikTok’s Algorithm Keeps Pushing Suicide to Vulnerable Kids. Published April 20, 2023. TikTok’s Algorithm Keeps Pushing Suicide to Vulnerable Kids.

2. Moyer MW. Kids as Young as 8 Are Using Social Media More Than Ever, Study Finds. The New York Times. Kids as Young as 8 Are Using Social Media More Than Ever Study. Published March 24, 2022.

3. Luguri J, Strahilevitz L. Shining a Light on Dark Patterns. SSRN Electronic Journal. 2019;13(1). doi:https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3431205

4. Karagoel I, Nathan-Roberts D. Dark Patterns: Social Media, Gaming, and E-Commerce. Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting. 2021;65(1):752-756. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1071181321651317

5. Monge Roffarello A, De Russis L. Towards Understanding the Dark Patterns That Steal Our Attention. CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems Extended Abstracts. Published online April 27, 2022. doi:https://doi.org/10.1145/3491101.3519829

6. Newberry C. How the TikTok Algorithm Works in 2020 (and How to Work With It). Social Media Marketing & Management Dashboard. Published February 8, 2023. 2023 TikTok Algorithm Explained and Tips to Go Viral.

7. Sha P, Dong X. Research on Adolescents Regarding the Indirect Effect of Depression, Anxiety, and Stress between TikTok Use Disorder and Memory Loss. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021;18(16):8820. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18168820

8. Novak S. TikTok’s Algorithm and How It Affects Your Viewing Experience. Discover Magazine. 2023 TikTok Algorithm Explained + Tips to Go Viral. Published June 12, 2023.

9. Vogels EA, Gelles-Watnick R, Massarat N. Teens, social media and technology 2022. PEW Research Center. Published August 10, 2022. Teens, Social Media and Technology 2022.

Biography

Angela Liddle has held the role of President and CEO of Pennsylvania Family Support Alliance for more than 25 years. She is responsible for the daily administration of the organization and ensures the organization provides an array of quality-driven program services for the prevention of child abuse statewide. She serves as the spokesperson for the news media and is directly involved in the organization’s interaction with state-level public policymakers, Pennsylvania’s congressional delegation, public and private funders, and stakeholders. Angela was selected by Gov. Tom Corbett to serve on the Children’s Trust Fund governing board of directors, where she served as vice president for more than twelve years. She currently serves as an officer on the national board for the Children’s Trust Fund Alliance.

Contact Information

Angela Liddle, Pa Family Support Alliance

2000 Linglestown Road, Suite 301

Harrisburg, PA 17110

(717) 238-0937

https://pafsa.orgMalishchak | 45-53

Volume 12 ► Issue 3 ► November 2023

Alone: Suicide Prevention in the Pennsylvania Department of Corrections

Dr. Lucas D. Malishchak, DBA

Abstract

A recent cluster of suicides within the Pennsylvania Department of Corrections (PDOC) facilities led to a review of suicide data, identification of an inadvertent error in the data collection process, and numerous transformative revisions to PDOC’s suicide prevention efforts. Revisions have included but are not limited to single celling procedures, the utilization of suicide risk assessments with making housing decisions, and enhancements in understanding the connection between violence and suicide risk in prison, as well as the connection between State Correctional Institutions’ physical plant layouts and protective factors of suicide in prison.

A few years ago, the

Pennsylvania Department of Corrections (PDOC) experienced a cluster of suicides

within a short period of time. After each suicide, PDOC adhered to our standard

suicide clinical review process in an effort to identify areas of improvement

or needed remediation. Our Psychology Office also reviewed the cluster of

suicides together as a whole, to identify any broader systemic concerns that

may have occurred. In this cluster review, we identified that the percentage of

individuals categorized as “double celled” at the time of their death – meaning

they had a cellmate assigned to their cell – appeared high based on our

previous experience reviewing and understanding suicides. Consequently, we

re-reviewed each suicide within the cluster and discovered that in fact only

one of them was technically double celled at the time of the suicide; that is,

in only one instance was the cellmate present in the cell when the decedent was

discovered.

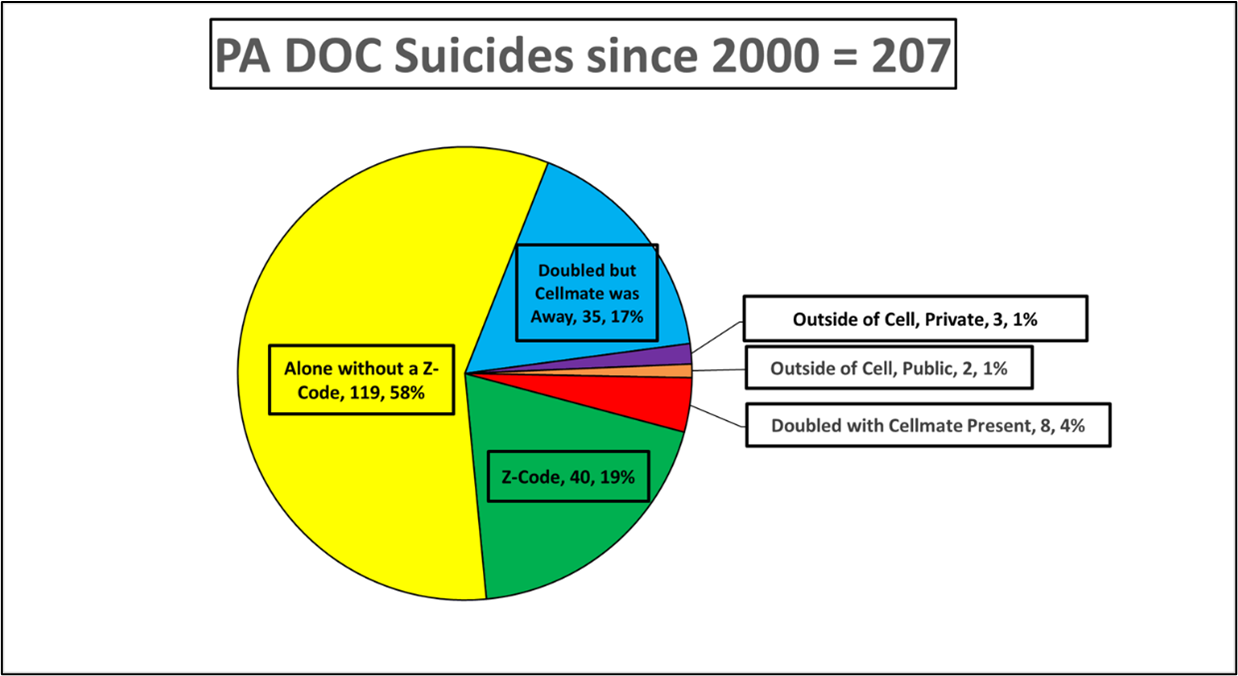

In the other four cases, although the individuals were categorized as double celled, they did not initiate the suicide until their cellmate was away or had exited the cell. The individuals were actually alone in the cell by themselves at the time they initiated their suicide. Upon discovering this inadvertent data collection error, we initiated a larger retrospective review of all suicides that had occurred within PDOC since 2000 in an effort to clarify the precise housing status of each decedent at the time of their discovery. Looked at through the lens of our new understanding of the concept of being double celled versus being alone, our review of this larger dataset revealed the same error in our understanding and categorization of housing status. The result was staggering: in 95% of all suicides that have occurred within the PDOC since 2000 – 174 of 184 – the individual was alone in a cell at the time of the suicide. The pie chart on the next page tells the entire story.

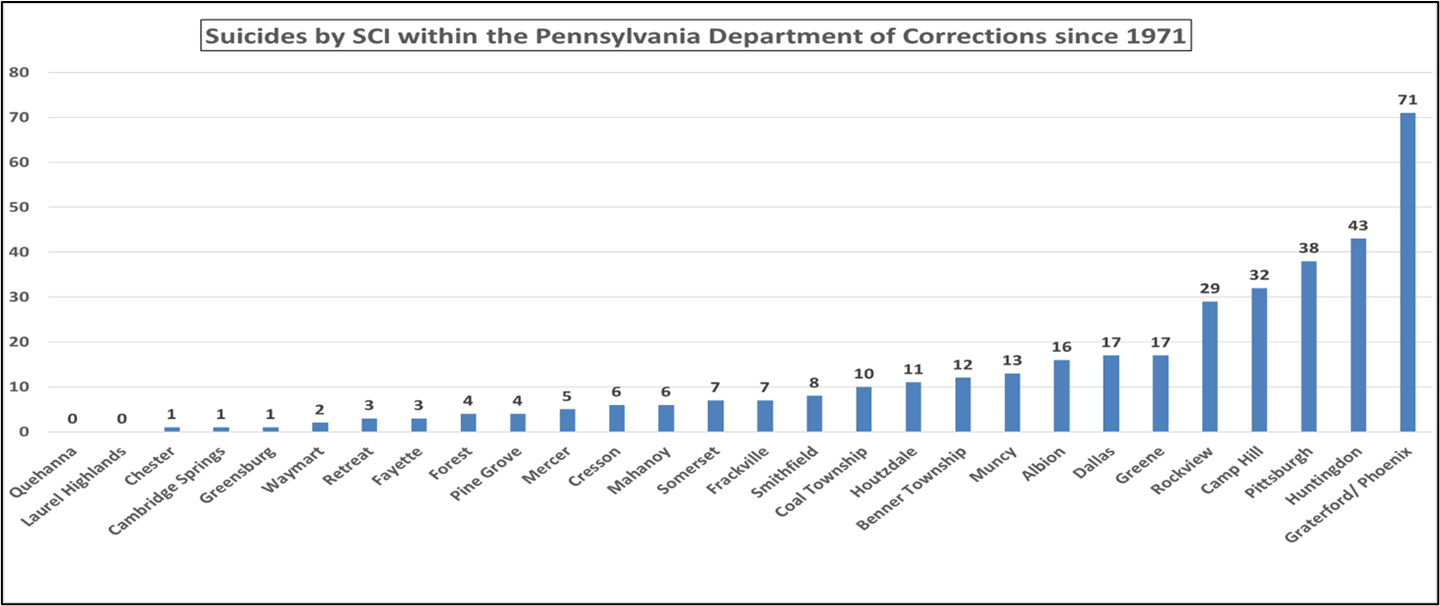

For reference, a Z-code indicates the person is assigned to a single cell (i.e., they are not assigned a cellmate). Once we discovered the “alone” issue, we wanted to further examine the data beyond our categorization error. We thought it would be helpful to know which specific PDOC prisons had experienced the most suicides during the past 50 years, so that we could strategically focus planned corrective interventions. We plotted exactly where – at which state correctional institution – each of 342 suicides had occurred since 1971.

Asking the Right Question

The 50 years of data revealed that certain prisons had experienced significantly more suicides than others. We asked ourselves, “What are those institutions doing so wrong?” It seemed obvious that we would find what we needed to know in the answer to that question. After some deliberation, we realized at least two reasons those prisons had experienced the most suicides: they have been open the longest, and they are some of our largest prisons. It immediately became clear that we were asking the wrong question. The better question was, “Which prisons have had the fewest suicides and why?” We identified four State Correctional Institutions (SCI) that were at least 30 years old and had very few suicides: Quehanna Boot Camp, SCI-Cambridge Springs, SCI-Laurel Highlands, and SCI-Waymart.

We were surprised to find that all four

facilities house populations known to be at increased risk of suicide: Quehanna

Bootcamp houses and treats predominantly younger (under 40) people with drug

and alcohol treatment needs. SCI-Cambridge Springs specializes in housing

females, who report or experience higher rates of mental illness and serious

mental illnesses than men. SCI-Laurel Highlands specializes in delivering the

highest level of acute medical care in our system, including care for people

who are terminally ill or near end of life. SCI-Waymart is responsible for delivering

PDOC’s highest level of inpatient mental health care and specializes in housing

our most seriously mentally ill male individuals. Despite high-suicide-risk

patient populations, those four SCIs, looked at together, had only ever

experienced two suicides. That finding was counterintuitive to what we thought

we knew about suicide risk. How were those institutions, which house apparently

higher-risk populations, having so much success at preventing suicides?

We informally interviewed staff from each

of the prisons and asked, “What are you doing differently?” Their answers were

consistent: "We’ve learned how to work effectively with these populations.

We know how to keep them safe. We treat them professionally and humanely; we

speak to them and treat them with respect." That seemed like a plausible

explanation, but it didn’t quite fit with what the data was telling us. While

we agreed that our staff at these institutions were professional, we thought

there may be something more going on, and in fact there was. At each of these

four prisons, there are very few cells. Most of their physical plants are

essentially open-dorm style settings. Most individuals are housed in large open

areas, visible to many other people, which creates infrequent “alone time.” In

addition to their excellent staff, one potential reason these prisons had so

much success in preventing suicides was that the individuals in these settings

were rarely housed alone.

Suicide

and the Pandemic

The number of suicides

recorded in PDOC prisons since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic appears

to corroborate the psychology office’s data findings. Given the significant

change, stress, loss, and unpredictability associated with this crisis, one would

expect the number of suicides to rise. During COVID, however, the total number

of suicides within PDOC prisons decreased by more than 50%, compared to the

same amount of time immediately preceding the start of the pandemic. How do we

explain that significant reduction? It might have been our reduced population,

a new Suicide Risk Assessment tool, enhanced training and communication, better levels of

supervision, or maybe even something else. One of the preventative actions

PDOC, like other correctional jurisdictions enacted to mitigate the risk of

spreading COVID-19, was to enhance movement restrictions within our population.

Many activities that during normal operations take people out of their cells

and create an opportunity for those who are double celled to be alone – for

instance going to school, work, or even to the day room to play chess – were

suspended. In an effort to protect our staff and population from spreading

COVID-19, we unintentionally decreased the amount of time alone experienced by

those who were double celled. We believe this partly explains why PDOC did not

have a single suicide categorized as “Doubled but cellmate was away” throughout

the entire pandemic, but had

experienced at least one of those types of suicides in 16 of the 18 years prior to the pandemic.

After putting all the

pieces together, it seemed clear to us that double celling or having a cellmate

present is a strong protective factor against suicide.

Our next step was to critically review our operational policies and practices. We began with a review of our Z-code policy, which outlined operational standards and guidelines for single and double celling. We discovered that our Z-code policy indicated that having mental health problems or a history of being dangerous toward self, self-mutilative, or unable to care for self were acceptable singular reasons to consider housing someone in a single cell. Our data, however, suggested that those reasons, taken alone, were likely contraindicated for being housed alone. As a result, we took immediate action and issued a memo to the organization revising the Z-code policy to prohibit assigning Z-codes for those contraindicated reasons. Additionally, we directed that all SCIs commence meaningful reviews of all individuals single celled at that

time to determine whether the individual could be safely double celled. Other improvements we have implemented, based on this suicide data review:

- Increased the frequency of security rounds on all Restrictive Housing Units and Special Management Housing Units statewide, from once every 30 minutes to unpredictable intervals with no more than 15 minutes between checks, with special emphasis on those individuals housed alone. By increasing the frequency of security rounds, we decreased the amount of time that people who are housed alone, are alone.

- Increased emphasis on out-of-cell clinical encounters with individuals housed alone on all Restrictive Housing Units and Special Management Housing Units, by assigning additional psychology staff to these units.

- Developed enhanced psychological evaluations for Z-codes, which now include a suicide risk assessment, violence risk assessment, review of objective testing, review of records, patient interview, and discussion with other staff members who know the patient well.

- Augmented pre-service and annual in-service suicide prevention trainings for all contact staff to include the results of this data review and relevant operational updates. Additionally, we emphasize that all other suicide prevention efforts currently in place must continue.

Through this process, the PDOC’s Psychology Office explored possible explanations for this “Alone Effect.” We tried to answer the question of why prison suicides appear to happen so rarely among people who are double celled but so often amongst those who are housed alone. The Psychology Office believes there are several potential explanations. First, if a cellmate is present, that cellmate can provide immediate rescue or intervention (i.e., to the person who is attempting suicide). Similarly, if a cellmate is present, that person can immediately call professional custody staff for help. Also, if a cellmate is present, that person may act as a deterrent simply by being present. A cellmate, if present, may offer protection against the fluctuating nature of suicide risk and or inaccurate assessments of suicide risk by correctional professionals. Likewise, if a cellmate is present, their presence may offer protection against those who falsely deny suicide intent to correctional professionals. Additionally, we believe that if a person is double celled with another person, their chances of developing their social support network, a known protective factor against suicide, is greatly increased. Finally, we believe there is a strong association between people assessed to be at high risk of violence and increased risk of suicide in prison, given that one of our primary violence risk mitigation interventions in prison is to cell violent people alone.

And that is how a fortuitous error helped advance PDOC’s understanding of suicide prevention and led to transformative changes.

Reprinted with permission from the National Commission on Correctional Health Care, CorrectCare magazine, copyright 2022.

Biography

Dr. Lucas D. Malishchak has been the Director of the Psychology Office for the Pennsylvania Department of Corrections since 2017. In this role, Lucas oversees a team of four Regional Licensed Psychologist Managers, who are together responsible for the clinical and administrative oversight of the mental health care system of Pennsylvania’s 24 State Correctional Institutions, which includes an infrastructure that supports more than 35,000 incarcerated people and more than 300 mental health care professionals. Lucas’ Doctor of Business Administration degree included a specialization in Criminal Justice. His dissertation was titled, “Alternatives to Segregation and Seriously Mentally Ill Inmates in Pennsylvania State Prisons: A Case Study of Employee Perceptions.”

Contact Information

Pennsylvania Department of Corrections

1920 Technology Parkway

Mechanicsburg, PA 17050

717-728-2093

Corr | 54-60

Volume 12 ► Issue 3 ► November 2023

More Health Care System Interventions Needed to Curb Veteran Suicide Rate

Universal screening can help more effectively determine risk

Allison Corr

Suicide is a major public health challenge that disproportionately affects veterans—both men and women—in the U.S. In 2020, the rate among this group was 57% higher than their non-veteran counterparts, according to the 2022 National Veteran Suicide Prevention Annual Report1 by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA). Pennsylvania has steep disparities as well: The rate of veteran deaths by suicide was 86% higher than the overall state suicide rate. The VA report, published in September 2022, also discussed the federal government’s comprehensive public health strategy2 to improve suicide prevention interventions for veterans. Included in these efforts is the practice of universal suicide risk screening to help stop these preventable deaths.

Research suggests that a multitude of factors contribute to the risk of suicide among veterans.3 Military service can lead to post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, substance use disorders, and chronic pain and other serious health conditions. To make matters worse, too often veterans experience systemic barriers to accessing critical health care. The VA states that preventing suicides is its top clinical priority4, and has made resources available, including evidence-based therapies, mobile apps to promote mental health, and special training for anyone who encounters a veteran in crisis. Yet administrative and bureaucratic challenges, including availability of providers5, long wait times, and financial qualifications6, are ongoing obstacles in some places, and can discourage veterans from getting the care they need.

However, many veterans who die by suicide utilized health services, including through the Veterans Health Administration (VHA), in the weeks or months leading up to their deaths. The VA reported that in 2020, 40% of veterans who died by suicide had a VHA encounter in the year of their death or year prior. Previous research found that 56% of male VHA patients with substance use disorders7 who died by suicide had a VHA encounter in the month before death, and 25% in the week prior. These health care visits are critical opportunities to identify patients experiencing suicidality—which includes suicidal thoughts, plans, deliberate self-harm, and suicide attempts—and connect them to evidence-based treatment.

Universal screening

In 2018, the VA published a 10-year broad public health strategy8 on preventing suicide among veterans. This comprehensive, interagency approach includes implementing effective treatment and support services for veterans already identified as high risk. It also emphasizes the importance of strengthening clinical and community suicide prevention initiatives, including universal screening.

This screening practice means that all patients are briefly assessed for risk of suicide upon intake at a health care setting, regardless of whether they are exhibiting signs of suicidality. Research shows that universal screening is effective9 at identifying a greater number of people experiencing suicide risk compared with assessing only those seeking behavioral or mental health care. The results of a recent study looking at VHA data suggests that screening all veterans in these settings,10 not only veterans seeking mental health treatment, will help ensure individuals experiencing suicide risk receive appropriate care.

Patient data from hospitals and health systems outside of the VA show similar results. When looking at the general population, research reveals that about half of people who die by suicide see a health care professional10 in the month before their deaths. More than half of the people who die by suicide11 do not have a known mental health condition. However, including universal screening as part of comprehensive suicide care can help prevent suicides. A study of eight emergency departments showed that universal suicide risk screening helped12 identify twice as many people who were at risk for suicide compared with screening only patients presenting with psychiatric symptoms. Researchers have also found that universal screening followed by evidence-based interventions13 reduced total suicide attempts by 30% that year.

Despite some concerns from health care providers, talking about suicide does not increase risk14 of suicidal thoughts or behavior. Evidence indicates that suicide risk screening is not associated with increased suicidality;15 on the contrary, directly communicating with patients about suicide helps identify at-risk individuals and connect them to treatment. Incorporating universal screening is even feasible without disrupting workflow,16 with an initial screening taking less than a minute17 and covered by public and private insurance. All patients, veteran and civilian, can and should be asked a few simple questions to determine suicide risk so they have an opportunity to receive care.

Although there is no simple solution to the devastating problem of suicide among veterans, there are evidence-based preventive measures and interventions that can help save veterans’ lives. The place to start is expanded and improved suicide screening to ensure veterans receive the critical treatment and support services that they need.

Allison Corr works on The Pew Charitable Trusts’ suicide risk reduction project.

If you or someone you know needs help, please call or text the Suicide and Crisis Lifeline at 988 or visit 988lifeline.org and click on the chat button.

References

1. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention Annual Report. (n.d.). 2022. Retrieved November 2023 from https://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/suicide_prevention/data.asp.

2. The White House, Reducing Military and Veteran Suicide: Advancing a Comprehensive, Cross-sector, Evidence informed Public Health Strategy. (n.d.). 2021. Retrieved November 2023 from https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/Military-and-Veteran-Suicide-Prevention-Strategy.pdf.

3. Yedlinsky, N.T., Neff, L.A., Jordan, K.M. Care of the Military Veteran: Selected Health Issues. American Family Physician. 2019; 100(9):544-551 https://www.aafp.org/pubs/afp/issues/2019/1101/p544.html.

4. U.S Department of Veterans Affairs. (2023). Suicide Prevention. Retrieved November 2023 from: https://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/suicide_prevention/.

5. RAND Corporation. Veterans' Barriers to Care. Retrieved November 2023 from: https://www.rand.org/health-care/projects/navigating-mental-health-care-for-veterans/barriers-to-care.html.

6. Cheney, A.M., Koenig, C.J., Miller, C.J. et al. Veteran-centered barriers to VA mental healthcare services use. BMC Health Services Research 2018; 18 (591). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-018-3346-9.

7. Ilgen M. A., Conner K.R., Roeder K. M., et al. American Journal of Public Health. 2012; 102: S88–S92. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300392

8. U.S. Department of veterans Affairs. National Strategy for Preventing Veteran Suicide. (n.d.). Retrieved November 2023 from:https://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/suicide_prevention/docs/Office-of-Mental-Health-and-Suicide-Prevention-National-Strategy-for-Preventing-Veterans-Suicide.pdf.

9. Mizzi A.K. Suicide Risk Screenings Can Save Lives. The Pew Charitable Trusts. 2022. Retrieved November 2023 from: https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/articles/2022/01/25/suicide-risk-screenings-can-save-lives.

10. Bahraini, N, Brenner, L.A., Barry, C., et al., Assessment of Rates of Suicide Risk Screening and Prevalence of Positive Screening Results Among US Veterans After Implementation of the Veterans Affairs Suicide Risk Identification Strategy. JAMA Network Open. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-014-2767-3.

11. Stone, D.M., Simon, T.R.S., Fowler, K.A., et. al., Vital Signs: Trends in State Suicide Rates — United States, 1999–2016 and Circumstances Contributing to Suicide — 27 States, 2015. CDC Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR). 2018. 67(22);617–624. Doi: https://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6722a1

12. Boudreaux, E.D., Camargo, C.A., Arias, S.A., et. al., Improving Suicide Risk Screening and Detection in the Emergency Department. American Journal of Preventative Medicine. 2015. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2015.09.029.

13. Miller, I.W., Camargo, C.A., Arias, S.A., Suicide Prevention in an Emergency Department Population. The ED-SAFE Study. JAMA Network. 2017; 74(6):563-570. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.0678

14. Mathias, C.W., Furr, R.M., Sheftall, A.H., et.al., What's the harm in asking about suicidal ideation? Suicide Life and Threatening Behavior. 2012; 42(3):341-51. doi: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22548324/.

15. Dazzi, T., Gribble, S., Wessley, S., et. al., Does asking about suicide and related behaviours induce suicidal ideation? What is the evidence? Psychological Medicine. 2014; 44(16): 3361-3363. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291714001299.

16. The Pew Charitable Trusts. Universal Screening Can Help Identify People at Risk for Suicide. 2022. Retrieved November 2023 from: https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/articles/2022/01/25/universal-screening-can-help-identify-people-at-risk-for-suicide.

17. The Pew Charitable Trusts. A Few Simple Questions Can Help Prevent Suicide2022. Retrieved November 2023 from: https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/fact-sheets/2022/08/02/a-few-simple-questions-can-help-prevent-suicide.

Biography

Allison Corr is an officer with Pew’s suicide risk reduction project, working with hospitals and health systems to implement evidence-based suicide prevention interventions. Previously, Corr was an officer with Pew’s dental campaign, focusing on efforts to expand access to oral health care for underserved populations. Before joining Pew, she worked on a range of health care issues for the Energy and Commerce Committee of the U.S. House of Representatives. Corr holds a bachelor’s degree in psychology from the University of Virginia and master’s degrees in public health and social work from Columbia University.

Contact Information

Nicole

Silverman

Communications Officer

nsilverman@pewtrusts.org

202-540-6964

Pringle & Moore | 61-68

Volume 12 ► Issue 3 ► November 2023

The Role of the Gatekeeper in Reducing Veteran Suicide

Dr. Janice L. Pringle and Dr. Debra W. Moore

In 2020, the University of Pittsburgh School of Pharmacy’s Program Evaluation and Research Unit (PERU) and Janice Pringle, Ph.D., received $3,500,000 in funding from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) new Comprehensive Suicide Prevention Program for Veteran suicide prevention in Northwest Pennsylvania. PERU’s Northwest Pennsylvania Veteran Suicide Prevention Program (NW PA VSPP) is a collaborative effort between healthcare partners, community organizations, and Veterans groups to create significant and lasting change in the 15-county region. The program aims to reduce veteran suicide attempts, injuries, and deaths by 10 percent (on average) over five years using the principles of the Zero Suicide framework and the Zero Suicide in Health and Behavioral Health Care model. Primary goals are improving access to treatment and support services, increasing awareness of suicide risk, and targeted suicide prevention activities and training opportunities.

Grounded in the Zero Suicide Model

Suicide is a growing public health crisis that took more than 48,000 lives in the United States in 2021, according to the CDC. In Pennsylvania alone, the rate of suicide deaths in 2020 was 13.25 per 100,000, compared to the national rate of 13.96 per 100,000.1 The Zero Suicide framework is based on the realization that people experiencing suicidal thoughts and urges often do not receive the care they need from a sometimes fragmented and distracted healthcare system. Studies have shown that most people who died by suicide saw a health care provider in the year before their deaths.2 This information presents an opportunity for healthcare systems to make a real difference by transforming patient screening processes and the care they receive. Throughout all 50 states and internationally, health and behavioral health systems implementing Zero Suicide have found success by adapting the model through the lenses of their care offerings and cultural considerations.

The Role of the Gatekeeper in Reducing Veteran Suicide