Positive Approaches Journal, Volume 13, Issue 3

| Site: | My ODP |

| Course: | My ODP |

| Book: | Positive Approaches Journal, Volume 13, Issue 3 |

| Printed by: | |

| Date: | Saturday, January 31, 2026, 1:57 AM |

Positive Approaches Journal | 6-7

Volume 13 ► Issue 3 ► December 2024

Community Safety and Wellness:

We All Belong Here

Introduction

A sense of belonging through community should be a fundamental right of all people. A world that is safe and promotes well-being for all will not only benefit the community being served, but also the individuals supported in the creation of relationships that foster understanding, compassion, and empathy, which can be navigated and mitigated. The community needs professionals and specialized services for individuals who may not have access to the mental health or intellectual disability and autism services.

Community safety and wellness are vital for the well- being of society and for the specific assistance identified. The acts of dedication build resilient, supportive, and inclusive communities. The direct assistance can take various forms and may alleviate immediate hardships. The service worker learns about the various needs, collaborates to address them through assessment, and then guides the individuals and families to the appropriate resources such as mental health, legal rights of community members, and child welfare. When done appropriately, the impact on community safety and wellness can be a tremendous vehicle for change, relief, and connection with relationships. Without programs and supports in place within the community, the potential pain of the lack of connection, support, and experiences of isolation may result in mental health diagnoses and other undesired outcomes for individual with developmental disabilities and autism.

In this issue of the Positive Approaches Journal, there will be a deep dive into the importance of community safety and wellness for individuals and families. Topics include emergency preparedness, interventions and programs for youth, justice and community supports and services, and navigating crises situations. Remember, a community that prioritizes health, safety, and well-being, is one that thrives and prospers.

Marlinda Smith, LCSW, BCD, NADD

Positive Approaches Journal | 8-11

Volume 13 ► Issue 3 ► December 2024

Data Discoveries

The goal of Data Discoveries is to present useful data using new methods and platforms that can be customized.

Utilizing Insights on Justice System Experiences to Drive System Improvements for Autistic People

As the prevalence of autism has increased over the years, so too have interactions between autistic people and the justice system. Across communities, these increased interactions have led to significant safety concerns for autistic people.1 High-profile instances of negative, and at times fatal, interactions between police and autistic people have led the autistic community to prioritize and focus extensively on community safety, training of professionals, and changes to practices across all aspects of the justice system. Differences in social and communication modalities that autistic people may present with, can complexify these interactions and risk negative outcomes. These differences, such as reduced eye contact and challenges responding to questions, may be misunderstood by law enforcement as guilt and noncompliance, and introduce risk for escalation and excessive force.

Police also acknowledge there is a disconnect between their knowledge and training, and the growing number of autistic people with whom they interact. Recent studies indicate that more than half of all police officers are not receiving any training on autism, or that their existing autism training was insufficient.2 However, continued efforts are critical, as a recent survey found that more than half of sampled autistic adults in the United States are fearful or hesitant to contact the police.3 This finding mirrors other research that prior interactions with police lead to distrust and reticence to contact police in the future, even during emergency situations.4 Given that autistic people experience high rates of victimization, and this is a leading cause for justice system involvement, any hesitancy to contact police because of an autism diagnosis is exceedingly consequential.

To understand the scope of encounters between the justice system and autistic people in Pennsylvania, the ASERT Collaborative launched the Pennsylvania Autism Needs Assessment (PANA) in 2017, which included a series of questions addressing justice system interactions. Survey data indicated that almost 20% of respondents had an interaction with the justice system (see Data Discoveries dashboard for more results from this survey). Among these instances, police were called in nearly two thirds of cases, and an arrest by police and a charge of a misdemeanor or felony was given in roughly 13% of these cases. Nearly 12% of justice involvement instances included the autistic person receiving probation or parole, and another 6% resulted in serving time in jail or prison.

These findings continue to motivate ASERT initiatives to support autistic people so that negative justice system interactions can be prevented, deescalated, and result in more equitable outcomes. ASERT has conducted training for professionals across all aspects of the justice system, reaching over 21,000 professionals in the state to date. These trainings offer a clinical overview of autism, but more importantly they provide professionals with tools and specific strategies that can be utilized in practice. Given the frequency that autistic people reported being arrested and charged with a misdemeanor/felony, this data has catalyzed a focus on supporting autistic people in courtroom settings through a partnership with the Pennsylvania Supreme Court and the founding of the Autism and the Courts Initiative. Through this collaboration, a virtual continuing legal education course was hosted for over 400 participants and training and education was provided to the Pennsylvania Parole Board. Although these efforts represent important achievements and point to tangible ways that ASERT is driving system-level changes to improve community safety, ASERT remains committed to continuing and expanding this work, while serving as a model for other states to replicate as they grapple with supporting growing numbers of autistic people in the justice system.

References

1. Cooper D, Frisbie S, Wang S, Ventimiglia J, Gibbs V, Love AMA, Mogavero M, Benevides TW, Hyatt JM, Hooven K, Basketbill I, Shea L. What do we know about autism and policing globally? Preliminary findings from an international effort to examine autism and the criminal justice system. Autism Res. 2024 Oct;17(10):2133-2143. doi: 10.1002/aur.3203. Epub 2024 Aug 5. PMID: 39104243.

2. Cooper DS, Uppal D, Railey KS, et al. Policy gaps and opportunities: A systematic review of autism spectrum disorder and criminal justice intersections. Autism. 2022;26(5):1014-1031.

3. Cooper Dylan, Steinberg Hilary, Hyatt Jordan, Shea Lindsay L. What’s the Point?: A Mixed Methods Inquiry of Reasons & Differences in Reported Fear or Hesitancy to Contact Police among Autistic Adults & their Caregiver. Academic Consortium on Criminal Justice Health. 2024.

4. Salerno AC, Schuller RA. A mixed-methods study of police experiences of adults with autism spectrum disorder in Canada. Int J Law Psychiatry. May-Jun 2019;64:18-25. doi:10.1016/j.ijlp.2019.01.002.

Hooven | 12-15

Volume 13 ► Issue 3 ►December 2024

How WE Can Keep Our Autistic Loved Ones Safer

Kate Hooven, MS

The PA ASERT (Autism Services Education Resources and Training) began training law enforcement and justice system personnel ten years ago. In that time over 20,000 police officers, corrections officers, judges, attorneys, and other justice system personnel have learned how to safely interact with individuals diagnosed with an autism spectrum disorder. As the Justice Project Coordinator for ASERT, I have conducted hundreds of trainings for law enforcement, as well as provided presentations for autistic individuals and their loved ones, on how to have safer interactions with law enforcement. Trainings for law enforcement include the common core traits and characteristics of autism, as well as tools and strategies on how to safely interact with individuals with autism. In ASERT’s trainings for individuals with autism and their family members, information on the role of police, what to do and what not to do if stopped by police, and practicing various role-play situations with a local police officer are shared. Both trainings are necessary for safer interactions between individuals with autism and law enforcement, as we all need better communication and understanding in order for everyone to be safer. However, at times, there appears to an “us vs them” mentality. “Us”, being the autism community, and “them”, being law enforcement, but when it comes to community safety, there should be no us or them, it should just be “we”.

Us

As the mother of a 23-year-old autistic son I want my son to feel safe and to be protected when he is out in the community. When he walks out the door of my home, or any door, I want him to walk back in that door in the same condition as when he left. I want law enforcement and other first responders (them) to keep my son safe when I am not present and to make them aware of his differences. I want “them” to understand the unique way my son communicates, thinks, and behaves. I want them to understand what autism looks like for my son. My son is unique with his own unique strengths and challenges and how can “they” keep him safe if my son or I don’t educate police on how to do so?

So why don’t “they” get all the training and why should our autistic loved ones, “us”, have to educate police? Because WE all need to do our part to keep everyone safer. I explain it to parents and caregivers who are upset that their loved one with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) or Intellectual Disability (ID) that we, as caregivers, should take on some responsibility when it comes to safety with law enforcement. We can’t continue to say “if you have met one person with autism, you have met one person with autism” and not want the police to understand how our “one person with autism” uniquely communicates, behaves, and interacts with the world.

Them

With my background as a former juvenile probation officer, who worked regularly with the Harrisburg Police Department, I know that in many instances, the police must act quickly for the safety of the individual, the community, and themselves. I am also aware that our law enforcement officers may not be educated about autism, intellectual disability, and other mental health struggles and they are not trained or expected to “diagnose” an individual on the street. Of course, a law enforcement officer’s job is to protect people and the community, and that means all people, so they most certainly should be made aware of how autism could impact an individual’s ability to communicate, follow commands, and respond appropriately. Police should at a minimum be made aware and able to recognize the characteristics and traits often associated with an autism spectrum disorder and be provided with tools and strategies on how to safely interact with an autistic individual. So yes, education plays a vital role for “them”.

We

If we want to keep our autistic loved ones safe, and if police and other first responders want to be safe when responding to calls, then WE need to all do our part. It’s always a game of finger pointing when something goes wrong, and in order to try and avoid that finger pointing, being proactive rather than reactive helps. Education and training for police is necessary, but so is making sure police are familiar with our autistic loved ones. Having a safety PLAN (Prepare Learn Advise Notify) in place for a possible interaction with law enforcement can make everyone safer.

Prepare an individual with autism on what they should do and not do when stopped by police.

Learn what a police officer may do for a traffic stop, or a mere encounter, and the safety strategies to keep an individual with autism safe.

Advise the police on how the individual with autism communicates, their sensory needs, behaviors they may have observed, or if they have eloped in the past and where to look.

Notify neighbors and other community members who may interact with an individual with autism of the behaviors they may not understand, so police aren’t called unnecessarily. Provide them with contact information for who they should call, rather than police, if the situation does not pose a threat to the individual or anyone else.

If we work together, if we all play our part, our individuals with autism and our law enforcement community will be safer, and at the end of the day, that is what we all want.

Biography

Kate Hooven, MS, is the Justice System Project Coordinator for ASERT (Autism Services, Education, Resources and Training) where she uses her background as a former juvenile probation officer to train justice system personnel, emergency responders, community agencies and providers. Kate is also the mother of three amazing children, including her 23-year-old son Ryan who was diagnosed with autism when he was four years of age. Ryan graciously allows Kate to share his experiences as an autistic individual, to personalize the ASERT trainings, as well as to raise awareness and promote acceptance for all autistic individuals.

Contact Information

Kate Hooven, MS

ASERT

Justice System Project Coordinator

Phone: 717-215-8364

Email: khooven3@gmail.com

Conte & Girandola | 16-21

Volume 13 ► Issue 3 ► December 2024

Police Department Mental Health Liaison Program

Vicky Conte & Candice Girandola

The Police Department Mental Health Liaison (PDMHL) program is a trauma-informed service administered and supervised by Pinebrook Family Answers in Allentown, PA.1 The program was implemented in April 2017 through a three-year Pennsylvania Commission on Crime and Delinquency (PCCD) grant administered by Lehigh County Mental Health. The PDMHL program works closely with the Allentown Police Department (APD), as well as the fourteen other Lehigh County police departments, to assess the needs of individuals who engage with the police, to refer individuals to the appropriate service providers, reduce recidivism, and to promote the Recovery Model.

The program began with just one social worker embedded within the APD in 2017. Although it took some time for the social worker to gain the trust of the APD officers, the social worker was supported by the current and subsequent police chiefs, and they routinely began sending referrals directly to the social worker. The relationship between the police departments in Lehigh County and Pinebrook Family Answers is based on mutual trust and on-going communication.1

As the program showed signs of success in its pilot years, Lehigh County Mental Health expanded the program in 2019, by adding another social worker to serve the other police departments in Lehigh County. In 2020, the APD granted Pinebrook Family Answers a contract to add a second social worker inside the APD. In 2023, Pinebrook Family Answers was granted another contract through Lehigh County to add three additional social workers. The PDMHL program currently receives funding for five social workers in total, two that serve the APD and three that serve the other fourteen police departments in Lehigh County, as well as any referrals that Magisterial District Judges may send the program, from their interactions with clients who have had engagement with the PA State Police.

There are several different titles used for police social workers across the country. Pinebrook Family Answers uses the title of Community Intervention Specialist (CIS) for police social workers embedded within the police departments in Lehigh County. Although there may be different position titles, the main goal of this position is to help individuals and families who have had engagement with law enforcement to connect with appropriate resources and service providers.

Working closely with law enforcement presents unique challenges, which require the CIS to sometimes think outside the box. When contacting individuals who have had contact with law enforcement, it was originally anticipated that those individuals would not be open to support and could be upset with law enforcement being mentioned. In Lehigh County, that could not have been further from the truth. Individuals are often grateful for any type of assistance, even a simple phone call from a CIS, allowing them to speak freely, which could de-escalate a situation.

Pinebrook Family Answers continues to experience a growing mental health crisis across Lehigh County. One of the biggest challenges for CIS is finding available resources for individuals. Although CIS can identify areas of need for an individual and recommend and refer them to appropriate providers, they are often met with extensive waiting lists or sometimes services that have been closed, due to a lack of funding. In many cases, CIS will step into the role of temporary case manager, checking in and meeting with individuals regularly until the referred individual begins services with a provider.

A critical piece of the CIS position is building trust and connecting individuals struggling with their mental health to community resources. Due to the state of their mental health and their past experiences, individuals who are referred to the CIS often do not trust providers or law enforcement. CIS work to build trust with individuals through honest communication, follow-through, and listening to individuals to uncover each of their unique challenges. As stated previously, simply listening to someone can help to de-escalate a situation.

Law enforcement have been supportive of the CIS program since its inception. One of the unexpected outcomes of the CIS position is educating law enforcement on the various human services departments and programs. Typically, officers will approach a CIS after they follow up with an individual and ask for an update on what can be done for that person. It is here that the CIS explain their plan to assist the individual, with respect to the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) and explain some of the roadblocks when it comes to getting individuals connected to resources. Law enforcement officers appreciate not only CIS follow-up, but also an explanation as to what is happening with the referred individual “behind the scenes”.

CIS receive referrals from the police in a few ways. The first referral stream is through police department administration sending referrals to the CIS via email. The second avenue to referral is through CIS interactions with police officers. CIS often go out and ride along with the police in the community. Through those interactions, police officers build trust in the CIS and then refer individuals directly to them.

The CIS have a unique working relationship with the Upper Macungie Police Department (UMPD). The UMPD adopted a HUB model a few years ago. The HUB model includes a monthly meeting hosted by the UMPD that many of the local service providers attend. The providers present at this meeting, discuss each case presented by the UMPD, and decide which service provider will take the lead on each case. The CIS work closely with the Community Resource Officer in the UMPD and they often go out and visit clients together.

Through interactions with the CIS, the PDMHL program can offer individuals who become engaged with the legal system, the opportunity to improve their outcomes with mental illness and/or substance use problems.1 This program also develops better community partnerships with law enforcement agencies and the courts. The PDMHL program’s goals are to connect individuals, including both children and adults, to appropriate resources, prevent unnecessary jail, prison, and hospital stays, to reduce recidivism, and to support recovery, for the benefit of the individual, their loved ones, and the community.

References

1. Conte V. Police Department Community Intervention Program. Pinebrook Family Answers. March 20, 2024. Accessed December 2, 2024. Police Department Community Intervention Program.

Biographies

Victoria (Vicky) Conte, is the Director of Community-Based Mental Health Programs for Pinebrook Family Answers in Allentown, PA. She has over 14 years of experience working in mental health services and over 12 years supervising person-centered programs in the Lehigh Valley. She assisted in the creation of the Police Department Mental Health Liaison Program in Lehigh County, PA, a program that supports individuals who encounter law enforcement in times of suspected mental health crises. Vicky also co-leads Pinebrook Family Answers’ Trauma-Informed Care Committee. She is passionate about bringing trauma-awareness to the community and trains other agencies and institutions in the Lehigh Valley and surrounding areas in trauma-informed care and vicarious trauma. Vicky is currently working on completing a master’s in Art Therapy at Cedar Crest College, Allentown, PA. Her certifications include a 50-hour trauma certification through Drexel University and certification as a trauma-informed agency trainer. In addition to her career in mental health, Vicky is interested in art, travel, and photography, as well as regularly practicing yoga. She is the mother of two young women whose accomplishments and drive to help others make her prouder every day.

Candice

Girandola, MPH, MS,

is a school based-therapist at Pinebrook Family Answers in Allentown, PA and has

over ten years of experience providing compassionate, client-centered care in

the community. While receiving her master’s in counseling, focusing on

trauma studies, Candice worked with individuals who encountered law enforcement

in times of crises and worked to help those individuals and their families with

connecting to appropriate resources in the community. Candice holds a master’s

in Clinical and Counseling Psychology from Chestnut Hill College, Philadelphia

PA, and a master’s in Public Health from East Stroudsburg University, East

Stroudsburg, PA. She has worked in various environments, including

nonprofit organizations, in-home mental health programs, government agencies,

and has collaborated with multidisciplinary teams to address complex client

needs. In addition to her professional career, Candice is passionate about

providing mindfulness practices to her community. She completed a 200-hour

Yoga teacher training in 2017 and regularly attends trainings centered around

mindfulness and trauma-informed care.

Contact Information

Vicky Conte

Director of Community-Based Mental Health Programs, Pinebrook Family Answers

Email: vconte@pbfalv.org

Candice Girandola, MPH, MS

Pinebrook Family Answers

Email: cgirandola@pbfalv.org

Cramer & Lubetsky | 22-27

Volume 13 ► Issue 3 ► December 2024

Aid in PA: Resources for Emergency Preparedness

Ryan Cramer, LSW & Martin Lubetsky, MD

Background

As the COVID-19 pandemic began, it became evident that there was a need for an accurate source of emergency information and resources for Pennsylvanians who are autistic and/or have an intellectual/developmental disability (IDD). Through a collaboration of the Autism Services, Education Resources and Training Collaborative (ASERT), Health Care Quality Units (HCQU), Philadelphia Autism Project, and Pennsylvania’s Office of Developmental Programs (ODP), the Aid in PA website (Aid in PA) was launched. Included on the site were webinars, developed printable resources, and links to information from trusted sources. Over the last four and a half years, Aid in PA has evolved. The focus of the site has expanded to address resource needs of a wider range of challenges and trauma support, and to include emergency preparedness.

Emergency Preparedness

The International Federation of Red Cross & Red Crescent Societies defines emergency preparedness as “the capacity of individuals, communities, and organizations to anticipate, respond to, and recover from emergency or disaster situations1.” Emergency experiences are traumatic for all people but can present unique challenges for individuals who are autistic and/or have Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities (IDD) and those who support them. Quickly processing and responding to change and coping with stress are just some of the components of an emergency that may be particularly difficult for this community.

Available Resources

ASERT has developed resources that can be used to help prepare for emergencies and disasters that most often occur in Pennsylvania. These resources focus on the needs of the autistic and IDD communities. Resources are developed with the input of self-advocates, those that support them, and experts in emergency preparedness.

Disasters that Happen in Pennsylvania

There are several disasters that can occur in Pennsylvania, which include both natural catastrophes and human-caused events2. One way to maintain safety in these disasters is to be prepared. A user-friendly and concrete way of presenting information on being prepared is using social stories. ASERT has developed social stories to assist individuals with understanding both the disaster, as well as how to be prepared for their occurrence. Some of the available social stories include: being prepared for a winter weather storm, a fire, a flood, thunder and lightning storms, extreme heat, and power outages. These are available for download at: Natural Catastrophe Social Stories — AID In PA.

During a natural disaster, it may not be possible to stay in your home or it may not be safe to stay there. It may be necessary to evacuate. This is a significant disruption to a routine and involves leaving very quickly from somewhere that is familiar. The resources at Aid in PA provide information on being prepared for evacuations by making a plan for “before” the evacuation, “during” the evacuation, and “after” the evacuation. Printable resources and a social story on evacuation during a disaster are available at: Evacuating Your Home During a Natural Disaster.

Social Story on Sheltering in Place

While evacuation during a disaster can be a stressful and disruptive experience, being asked to remain at home and shelter in place could potentially be just as disruptive. To prepare for sheltering in place and to ease some of the stress of the unknown, performing a periodic review of what to expect may be helpful. ASERT has developed a sheltering in place social story to assist with this review. The social story provides an overview of sheltering in place and what one may be able to do and not do during this emergency direction. This social story can be downloaded at: Shelter in Place Social Story.

Trauma Informed Emergency Shelter Tool Kits

A shelter is a place to go during natural disasters or conflicts, like when something happens in someone’s home. The purpose is to provide personal safety, protection from the weather, and disease prevention. A typical stay is for 12-72 hours (about three days) but can be longer when needed. Shelters provide basic needs such as: a safe space to get away from the emergency, restroom facilities, water, food, diapers, hygiene products like toothbrushes and soap, and medical assistance when necessary. Most people have never had to stay in a shelter before, so it can be a new and stressful experience. This is especially true for someone who may have difficulty communicating their needs and who may be overwhelmed due to change and sensory overstimulation.

ASERT, in collaboration with the PA Department of Human Services (PADHS), and Disaster Disability Integration Task Force, developed a set of trauma-informed emergency shelter narrative tool kits. PADHS provides several resources that can support people with disabilities and others with access and functional needs during disasters3. The purpose of the toolkits developed by ASERT and PADHS is to inform self-advocates, families, caregivers, and Direct Support Professionals on how to best support persons with sensory needs, including autistic individuals and individuals with intellectual disabilities, in a disaster shelter setting. Topics in the tool kits include: what to expect in a shelter, identifying and communicating needs, sensory needs, behavioral needs, physical health needs, social and communication needs, and dealing with trauma. The tool kits are available to be downloaded here: Emergency Preparedness Shelter Toolkits.

Summary

Being prepared for emergencies is vitally important for everyone. Being able to confidently respond to emergencies, often requires not only awareness of what to expect, but also having the opportunity to practice what you will need to do in these situations. Practice and rehearsal are often a very effective way to learn a variety of skills, and to be prepared for how you or someone you support or care about may react in what could be a very stressful time. The resources reviewed here are useful tools to assist with that process.

References

1. International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies. (2011). Disaster management: Strategy and coordination (MAA00029) – Global plan 2010–2011. Retrieved from Disaster and Crisis Preparedness.

2. Pennsylvania Emergency Management Agency. (n.d.). Most Likely Emergencies in Pennsylvania. Retrieved November 25, 2024, From Most Likely Emergencies in Pennsylvania.

3. Pennsylvania Department of Human Services. (n.d.). Mass Care and Emergency Assistance. Retrieved November 25, 2024, From Mass Care & Emergency Assistance | Department of Human Services | Commonwealth of Pennsylvania.

Biographies

Ryan Cramer is a Licensed Social Worker who has worked to support adults and children with intellectual and developmental disabilities for the last 30 years. He started as a Direct Support Professional in residential programs for individuals with complex needs. Throughout his career he has worked as an administrator of programs, a therapist, consultant, and trainer. Ryan currently manages all training, outreach, and resource development initiatives in the ASERT Western Region Collaborative at UPMC Western Behavioral Health’s, Center for Autism and Developmental Disorders.

Martin Lubetsky, M.D., is a professor of Psychiatry at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, and Senior Advisor of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Center for Autism and Developmental Disorders at UPMC Western Psychiatric Hospital. Dr. Lubetsky has worked in the clinical, training, administrative, and research areas of autism, developmental disabilities, and child and adolescent psychiatry for over thirty-eight years. He provided diagnostic and clinical services to children, adolescents, and adults with autism spectrum disorder, and intellectual disabilities with mental health issues. He has been active in developing awareness and support for the growth of community-based services. He is co-editor of the book Autism Spectrum Disorder, Oxford University Press, Inc.

Contact Information

Ryan Cramer, LSW

Assistant Director, ASERT Collaborative

Email: cramerrd@upmc.edu

Martin Lubetsky, M.D.

Director, ASERT Collaborative

Email: lubetskymj@upmc.edu

Lawrence | 28-32

Volume 13 ► Issue 3 ► December 2024

Pennsylvania Crisis

Intervention Teams: Enhancing Police Responses to Mental Health Crises

Bobbi

Lawrence, LSW

In recent years, mental health crises have increasingly become a significant challenge for law enforcement agencies across the United States. Pennsylvania is no exception. To address these challenges, many police departments in Pennsylvania have implemented Crisis Intervention Teams (CITs). These teams are designed to improve the way law enforcement officers respond to individuals experiencing mental health crises, emphasizing de-escalation, diversion from the criminal justice system, and increased collaboration with mental health professionals. The CIT model represents a critical shift toward more humane and effective responses to situations that have traditionally fallen solely within the purview of law enforcement.

The CIT model was first developed in Memphis, Tennessee, in 1988, but has since been adopted by police departments nationwide. In Pennsylvania, the CIT program began gaining traction in the early 2000s in response to growing concerns about the intersection of mental illness and the criminal justice system. Pennsylvania’s CIT programs aim to address the inadequacies of traditional law enforcement responses to mental health crises, where individuals with mental illnesses were often arrested and jailed, rather than receiving appropriate care.

A key feature of CITs is the specialized training provided to police officers. In Pennsylvania, CIT officers undergo a 40-hour training program that includes instruction on mental health diagnoses, de-escalation techniques, and strategies for dealing with individuals in crisis. Officers also participate in role-playing exercises and hear directly from individuals with lived experience of mental illness. This training equips officers with the skills to recognize when someone is in crisis and how to intervene safely and effectively, reducing the likelihood of violent confrontations.

One of the central goals of CITs in Pennsylvania is to divert individuals with mental health issues away from the criminal justice system and toward treatment. CIT officers are trained to identify situations where mental illness is a significant factor and to connect individuals with the appropriate resources, such as mobile crisis units, mental health clinics, or hospitals. In some cases, CIT officers may even be able to resolve a crisis without making an arrest through de-escalation or by facilitating voluntary treatment.

The impact of CITs on police departments and communities in Pennsylvania has been profound. Studies show that CIT-trained officers are less likely to use force in situations involving mental health crises. For example, a 2020 study of CIT programs in Pennsylvania found that departments with CIT officers reported fewer injuries to both officers and civilians during crisis incidents. Additionally, there was a notable reduction in arrests of individuals with mental illnesses, as officers were more likely to refer them to mental health services rather than jail.

Beyond immediate crisis intervention, CITs foster stronger relationships between police departments and mental health agencies. This collaboration ensures that officers have access to a network of professionals who can assist with crisis situations. Some departments in Pennsylvania have even partnered with mental health professionals who accompany officers on calls, further improving outcomes for individuals in crisis.

While CIT programs have shown promise in Pennsylvania, there are still challenges to address. One significant issue is the uneven implementation of CIT programs across the state. In rural areas, where resources are limited, it can be difficult to provide the same level of CIT training and support that is available in larger cities. Additionally, mental health services in these areas may be sparse, limiting the ability of CIT officers to refer individuals to appropriate care.

There is also the broader challenge of police culture. While many officers embrace the CIT model, there are still those who view mental health crises as secondary to the primary law enforcement mission of crime control. Changing this mindset will require ongoing training, leadership support, and a shift in departmental priorities to focus more on public health and safety, rather than punishment.

In response to these challenges, Pennsylvania continues to expand its CIT programs and increase collaboration between police departments, mental health professionals, and community organizations. Some departments are exploring the possibility of co-responder models, where mental health professionals and police respond to crisis situations together, further reducing the likelihood of negative outcomes.

In conclusion, I personally have had the honor of being involved with the Pennsylvania CIT programs for the past 17 years and have witnessed firsthand the effectiveness of this model. One example would be from the city of Johnstown, where CIT officers routinely make visits to the local partial programs and Drop-In Centers. During these visits, officers can build connections with folks when they are doing well. These bonds have helped tremendously when the individual is having a mental health crisis, which warrants police involvement. It is exciting to know that Pennsylvania has taken an active stance on investing efforts to assist people with interventions over arrests, which has been shown to be effective for those struggling with a mental health crisis.

References

1. CIT International. Memphis Model. 2012 Retrieved from CIT: Community Partnerships Making a Difference.

2. Specialized Police Response in Pennsylvania: Moving Toward Statewide Implementation. Pennsylvania Mental Health and Justice Center of Excellence. Specialized Police Response in Pennsylvania: Moving Toward Statewide Implementation.

3. Deane MW, Steadman HJ, Borum R, Veysey B, Morrissey J. Emerging partnerships between mental health and law enforcement. Psychiatric Services. 1999;50(1):99–101. doi: 10.1176/ps.50.1.99. [Psychiatry Online: Emerging Partnerships Between Mental Health and Law Enforcement] [PubMed: Emerging Partnerships Between Mental Health and Law Enforcement] [Google Scholar: PubMed: Emerging Partnerships Between Mental Health and Law Enforcement].

4. NAMI (2020)—Crisis Intervention Team (CIT) Programs, Crisis Intervention Team Programs.

5. Compton MT, Broussard B, Munetz M, Oliva JR, Watson AC. The Crisis Intervention Team (CIT) Model of collaboration between law enforcement and mental health. Hauppauge, NY: Nova Science Publishers, Inc; 2011.

6. Northeastern Pennsylvania Crisis Intervention Team. CIT Improve Interactions Between Law Enforcement & Persons with Mental Illness.

7. Improving Crisis Response and Crisis Intervention Team Programs in Pennsylvania.

Biographies

Bobbi Lawrence, LSW, is the Executive Director of Pennsylvania’s Sexual Responsibility and Treatment Program at Torrance State Hospital. She has worked at the State Hospital for almost 20 years. She received her BS in HDFS at Penn State University and her MSW at the University of Pittsburgh. She has been providing training for the PA Crisis Intervention Teams (CIT) for the past 17 years to over ten counties and is one of the original members of the training team. She has also provided mental health training to the PA State Police SERT Negotiators, local police departments, and multiple courts and probation offices throughout Pennsylvania. She is an adjunct professor in the School of Social Work at the University of Pittsburgh and a Therapist for Switch Mental Health Services in Johnstown. In her free time she enjoys baking and participates in a variety of community organizations in her hometown of Portage. She is most proud of her two amazing sons who both serve in the United States Armed Forces.

Contact Information

Bobbi Lawrence, LSW | Executive Director

Department of Human Services | Torrance State Hospital

PA Sexual Responsibility and Treatment Program

Email: rolawrence@pa.gov

Walton & Daniels | 33-39

Volume 13 ► Issue 3 ► December 2024

THE POINT: Empowering Youth

Dwayne Walton & Sarah Daniels

THE POINT is an organization that provides an after-school community center, on-campus support and mentoring, and a program to support students in juvenile detention. We believe that our faith-based approach has been effective in helping students avoid negative interactions with law enforcement and keeping them out of the criminal justice system. Our mission is to empower youth and their families to live victorious lives. We provide a safe, engaging, and spirit-filled environment where young people can grow, develop resilience, and build a future of service to others. In 2023, we served 705 students and have already served 838 in 2024, offering a holistic program focused on emotional support, academics, spiritual growth, and community connection. Through these efforts, we strive to keep youth engaged and on positive paths, helping them avoid risky behaviors and potential interactions with law enforcement.

Empowerment Through Academic Support

THE POINT’s Academic Enrichment Program is foundational to our approach. With focused support, 86% of our participants report increased academic motivation, 77% see improved school performance, and 63% have advanced their literacy skills. We believe that a solid academic foundation empowers youth to envision a positive future and make decisions that will open doors for them.

Empowerment Through Engaging Programs and Activities

Our 33,000-square-foot facility includes a full basketball/volleyball court, outdoor skatepark, e-sports arena, art studio, vocational shop, music studio, and commercial kitchen. Programs offered in these spaces build confidence and essential social skills: 92% of students report increased self-confidence, 90% have made new friends, and 96% have built trusted relationships with adults. This support network keeps students connected, accountable, and focused on making positive choices.

Through our programs, students also learn to make healthy lifestyle choices. An impressive 90% of youth report avoiding alcohol, and 92% are steering clear of drugs and sexual activity. With 76% indicating they are getting into trouble less frequently; our program fosters the self-discipline and positive behavior that help youth avoid or minimize risks, such as fighting in the community, drug and marijuana use, and alcohol consumption. The more they attend the less likely they will face these temptations and stay focused.

Empowerment Through Envisioning the Future

Planning for the future is central to our programs. Eighty-two percent of participants have identified career goals, 64% intend to pursue college or technical education, and 18% aim to join the military. By helping young people envision and prepare for their future, we encourage them to prioritize education and growth over risky behaviors. With mentors and scholarships available to support them, youth are better equipped to follow positive paths and avoid negative influences.

Empowerment Through Leadership, Service, and Community Engagement

Leadership and service are key aspects of our mission. Ninety-one percent of youth have expressed a stronger interest in helping others, fostering responsibility and empathy. Our students have traveled to Montana to serve on the Crow Indian Reservation, using sports and community-building activities to foster friendships. These experiences broaden their perspectives and give them something positive to look forward to, further reducing the likelihood of risky behavior.

Empowerment Through a Safe and Supportive Environment

Safety and support are foundational at THE POINT, where 100% of students report feeling safe, and 99% feel supported and cared for. In this environment, youth can take positive risks and develop trusting relationships. We create a “safe place to fail,” where students who make mistakes are met with compassion and guidance rather than judgment. Caring adults walk them through accountability, forgiveness, and growth, fostering behavioral change rooted in grace and mercy.

Empowerment Through Mental and Spiritual Well-Being

Mental health is a priority at THE POINT, with 95% of students reporting increased happiness and 93% showing improved self-esteem. Our faith-centered approach is particularly impactful. Many youth arrive carrying burdens from trauma, harmful choices, and chaotic environments, which affect their mental health and sense of self-worth. Our program addresses these challenges with a focus on spiritual renewal. As students learn about God’s love in Christ, they discover hope, forgiveness, and the potential for a brighter future. We teach that they are created in God’s image, with unique gifts meant for building stronger families, communities, and lives.

Making a Lasting Difference

Our work would not be possible without the dedication of 364 volunteers who serve as mentors and role models to our youth. Together we’ve provided over 22,790 meals to food-insecure families, meeting immediate needs and reinforcing our broader mission.

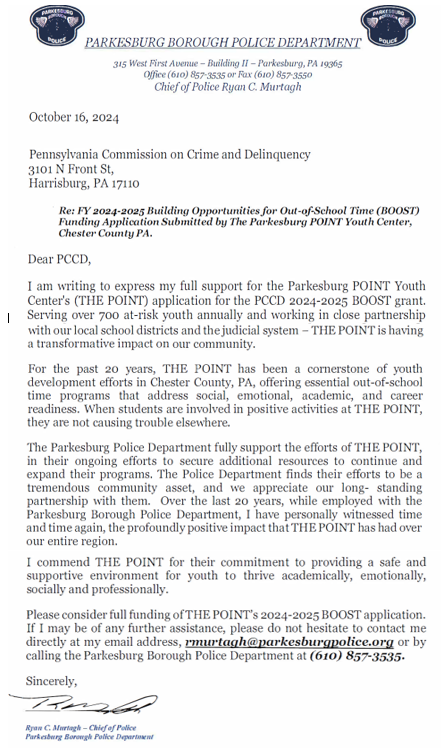

At THE POINT, we are committed to measurable, transformative impact in the lives of youth. Through meaningful engagement, academic and emotional support, and a foundation of faith, we help guide young people toward futures filled with hope, purpose, and achievement. The following is a letter from the Parkesburg Borough Police Department in support of THE POINT's Academic Enrichment Program.

Figure 1: Letter Received from Parkesburg Borough Police in Support of THE POINT's Academic Enrichment Program.

References

1. Conte V. Police Department Community Intervention Program. Pinebrook Family Answers. March 20, 2024. Accessed December 2, 2024. Police Department Community Intervention Program.

Biographies

Dwayne Walton, Executive Director at the Point, was born in Guyana, South America, and with his family, he immigrated to the United States in 1986. Dwayne grew up in Brooklyn NY and Queens NY. He attended Andrew Jackson High School, and began attending Philadelphia Biblical University, now Cairn University, in 1999. He graduated in 2004 with a BA in Biblical Studies and began working at the Parkesburg Point Youth Center as Executive Director. THE POINT is a Christian Outreach that aims to bridge churches with the community by providing a 33, 000 square foot community center dedicated to evangelism and discipleship. Over 50 churches are involved with THE POINT. Dwayne met his lovely wife Amy at THE POINT and the two were married in 2006. Dwayne and Amy have two wonderful kids, Elijah who is 16 and Eliana who is 14, and they live in Coatesville Pa.

Sarah Daniels, Director of Grants & Social Media at THE POINT, resides in West Chester, PA with her husband and two children. Sarah holds a Bachelor's degree in Human Development and Family Science and a Master's degree in Nonprofit Management. For 19 years, Sarah has been committed to supporting organizations that prioritize the health and well-being of women, children, and families. As the Director of Grants & Social Media at THE POINT, she plays a crucial role in sharing the organization's story, highlighting its impact, and securing essential resources to advance its mission.

Contact Information

Dwayne Walton | Executive Director, The Point

Email: dwayne@parkesburgpoint.com

Sarah Daniels | Director of Grants & Social Media, The Point

Email: sdaniels@parkesburgpoint.com